Before Black Lives Matter: Exhibition pays tribute to an earlier NYPD killing of unarmed black man

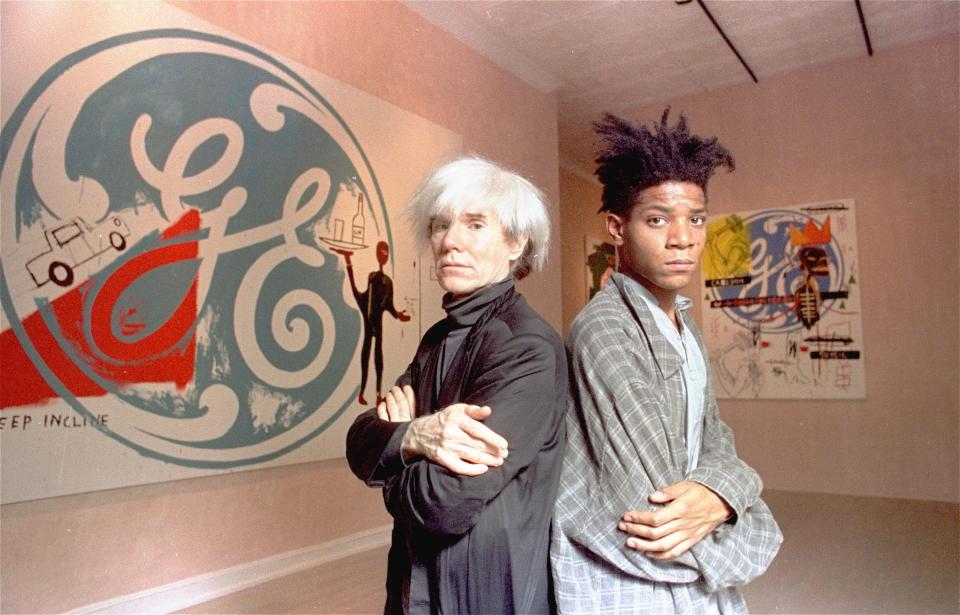

NEW YORK — He danced in Madonna’s first music video, “Everybody.” Tall and handsome, he did some modeling for the designer Dianne Brill, who was close to Andy Warhol. But his true passion was art, and so Michael Stewart was studying at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. In the early morning hours of Sept. 15, 1983, Stewart was returning to that borough, where he had been born and raised, after spending the evening with friends in Manhattan.

He never made it. On the platform of the Brooklyn-bound L train at the First Avenue station, at about 3 o’clock in the morning, transit officers of the New York Police Department supposedly caught him spray-painting graffiti on a wall. Cops say that Stewart was initially compliant but then tried to break free. A friend who had been with him believes they were furious because they’d seen Stewart, a black man, kiss her, a white woman. The officers dragged Stewart up the station stairs and, according to witnesses, threw him down and beat him.

They allegedly continued to assail Stewart in the police van that took him to a Union Square police station, where a New York University student says she heard him scream: “Help me.” Nobody did. The officers did finally transport Stewart to Bellevue, the troubled public hospital on Manhattan’s East Side. It was too late. Thirty-two minutes after he’d been apprehended underground by the police, Stewart was in a coma. He died two weeks later.

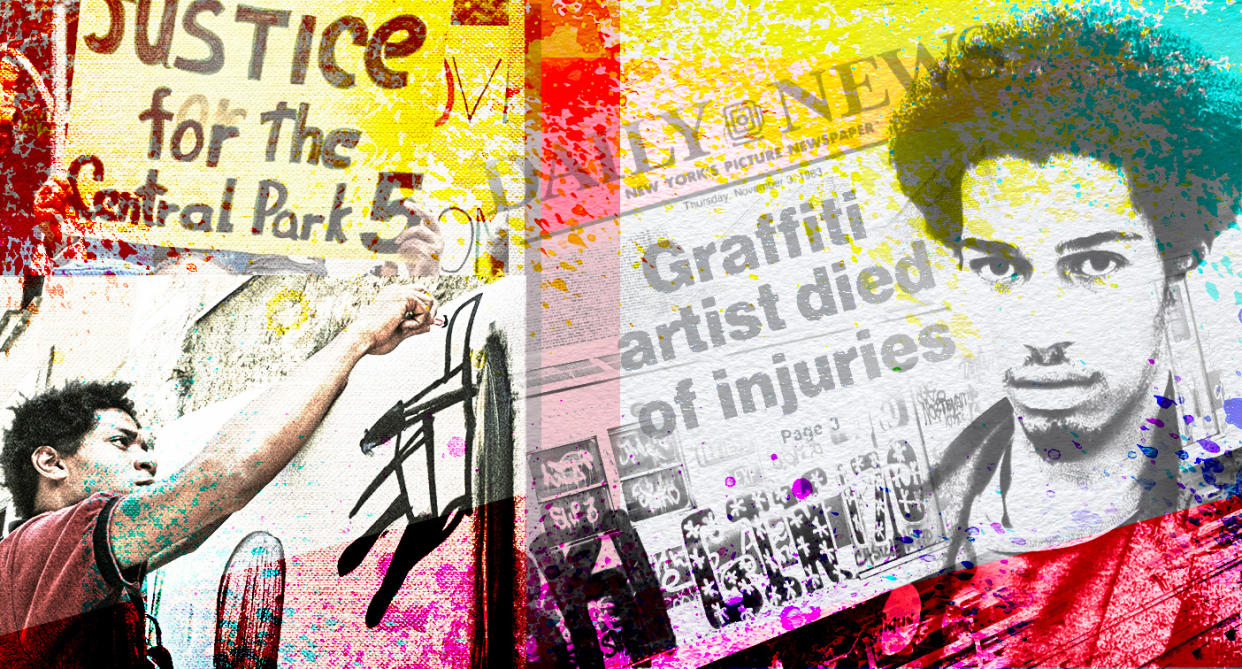

Many New Yorkers today are learning about Stewart’s fate for the first time — 36 years after his death — because his story is on vivid display in a current exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum, “Basquiat’s ‘Defacement’: The Untold Story.” “Defacement,” also known as “The Death of Michael Stewart,” is a Black Lives Matter painting created three decades before the movement against police brutality took hold. That painting is the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, who was born to a Puerto Rican mother and Haitian-American father and raised in relatively prosperous circumstances in brownstone Brooklyn. He dealt frequently with issues of race in his work but never as arrestingly as in his portrayal of two pink-faced cops beating a black figure into a shapeless pulp.

The show comes amid a broader reassessment of recent American culture, the 1980s in particular. This spring, director Ava DuVernay’s miniseries “When They See Us” offered a reassessment of the five young black men wrongly convicted of raping a jogger in Central Park in 1989. At the time, Donald Trump called for those young men, known as the Central Park Five, to be put to death. He has recently defended doing so, arguing that “you have people on both sides of that.” Those words were an echo, at least to critics, of Trump’s claim that there were “fine people on both sides” of a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Va., that descended into violence and left three dead. And more recently, Trump has opened a feud with the Rev. Al Sharpton, whom he has known — in part as a friend — for decades.

That led the MSNBC anchor Joy Reid to write on Twitter that “Trump has turned the whole country into 1980s New York,” reanimating the racial and cultural grievances of that time.

Trump built his eponymous tower on Fifth Avenue in 1979. Three years later, he appeared on the first Forbes list of wealthy Americans, though he vastly exaggerated his net worth in order to do so. It was also in that same year, 1982, that Basquiat, who had gotten his start as a graffiti artist known as Samo, entered a fecund period that would last for six years. During this time, he painted the works that would make him “America’s first truly important black painter,” as Vanity Fair would later write.

Basquiat wanted fame as badly as Trump, but whereas celebrity sustained Trump, it crushed Basquiat. Stardom made him miserable, and he fell into a deepening heroin addiction that claimed him on an August night in 1988. He was 27, just two years older than Stewart at the time of his death.

Stewart was largely forgotten, as the names of other black victims of racism (perpetrated by both officers and citizens) overtook his own: Michael Griffiths, Yusuf Hawkins, Amadou Diallo, Abner Louima, Sean Bell. Meanwhile, Basquiat’s stock has only kept rising, culminating in the $110 million sale of one of his paintings two years ago. “Defacement,” the painting now on display at the Guggenheim, was reportedly loaned to the museum by the musician and entrepreneur Jay-Z (the Guggenheim denied that he was the donor).

The show was organized by Chaédria LaBouvier, the first African-American to curate an exhibition at the Guggenheim. On a recent Sunday afternoon visit, the gallery was packed, even as Central Park beckoned from across Fifth Avenue with perfect summer weather. The museum was closing soon, yet a line of visitors waited eagerly to see the Basquiat exhibit. Among those waiting was an executive for Bomber, a company that makes high-end skis, include a collection adorned with Basquiat paintings. Those retail for $2,500. Forty years ago, you could have bought a Basquiat for practically nothing on a SoHo street.

The exhibition could not be more timely. A month after “Defacement” opened, the federal Department of Justice announced that it would not seek new charges in the death of Eric Garner, a black man who was killed in 2014 by an NYPD officer who used a prohibited chokehold to restrain him. The officers who killed Stewart in 1983 were tried and ultimately acquitted of all charges. Daniel Pantaleo, the officer who killed Garner, survived multiple legal challenges but was fired in late August after a sustained public outrage.

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, who won City Hall in 2013 on a social justice platform, did his best to say nothing about Pantaleo, even as presidential candidates challenged him on the issue repeatedly during the second Democratic primary debate.

“It’s almost as if God keeps giving us the same scenario and waiting for us to get it right,” says Hawk Newsome, a leader of Black Lives Matter in New York who grew up in the city in the 1990s.

Garner’s death has been considered by some as the watershed moment of Black Lives Matter. His last words, “I can’t breathe,” became a sort of rallying cry for the movement against police misconduct. But though it took place many years before social media had the power to galvanize millions, the killing of Michael Stewart — and the response to his death — proved an eerily prescient sketch of the contours along which the fight for social justice in law enforcement would be waged.

“It energized a lot of us,” remembers Sharpton of the Stewart killing. “Police brutality was more the norm than exception in our community,” he told me in a recent conversation. “We were radical outsiders. By the time of Garner, we had more political strength.” That strength was largely symbolized by de Blasio inviting Sharpton to City Hall to discuss the Garner killing. The meeting also included Police Commissioner William Bratton, whom Sharpton loudly criticized. Speaking five years later, Sharpton has no regrets about that confrontation.

Sharpton spent the 1980s and 1990s protesting racism in New York. Such efforts were sometimes greeted viciously, as when one furious white counterprotester in Brooklyn attempted to assault him with a watermelon. (There were also errors of judgment, which hound Sharpton to this day.)

Much as he believes in the value of activism, Sharpton admits that the biggest victory for social justice in law enforcement has been the advent of the body camera, which officers in New York and many other municipalities are now required to wear. “We didn’t have a tape with Michael Stewart,” he says, contrasting that with video of the Garner killing taken by bystander Ramsey Orta. “This is on tape — choking him.”

Charles Rangel, the longtime Harlem congressman, echoes that appraisal. “It’s hard for me to say there’s been an improvement,” he said in a recent conversation. Like Sharpton, he cited police cameras as the sole reason that police killings no longer encounter public (and prosecutorial) indifference. “Cops were able to create their own story” in the 1980s, Rangel says. And while that’s still possible even with body cameras, it is much more difficult to do.

Trump, Sharpton charges, is “trying to undo everything gained in the movement” that began in the 1980s, with the Stewart killing and other deaths of black men and women at the hands of police. “The challenge is that the rhetoric and the policy is headed back,” he says. “The question is whether or not there will be a resistance movement strong enough to face the tide and turn it around,” in the direction of justice once again. Otherwise, Sharpton warns, “the tide will drown us all.”

In his own way, Basquiat was fighting against that same tide. Several days after the Stewart killing, he painted “Defacement” on a wall in the lower Broadway studio of the painter and muralist Keith Haring. “He was completely freaked out,” Haring would recall of Basquiat’s reaction to the Stewart killing, “It was like it could have been him.” Haring cut the painting from his studio wall and had it lavishly framed. “Defacement” hung above Haring’s bed in his Greenwich Village apartment until his death from AIDS-related complications in 1990. A white native of Pennsylvania, Haring painted his own tribute to Stewart, a not entirely successful large-format work that has been lent to the Guggenheim.

Even if the paintings of Basquiat and Haring were not necessarily faithful to reality, they did what, today, social media can do far more quickly. “This was a form of evidence, in a sense,” curator LaBouvier told the New York Times. Her small but powerful exhibition chronicles how the insular lower Manhattan art community took up Stewart as a cause. This was largely because Stewart was involved in that scene himself and was close friends with Suzanne Mallouk, Basquiat’s sometime lover and muse.

“This incident electrified the scene,” recalled influential gallerist Jeffrey Deitch, “and people talked of nothing else for months.” Protests were organized by artists at Union Square and at the Manhattan Criminal Courts building on Centre Street. Danceteria, the famous club, held a benefit featuring Madonna. In a 1984 documentary made by Franck Goldberg, Madonna appears in an early scene. “Racism didn’t end after the ’60s,” she tells Goldberg.

Mallouk is in the documentary too. “I know in my heart that Michael was murdered by the police,” she tells Goldberg. Today a psychotherapist in Manhattan, she recalled the Stewart killing in an email exchange with Yahoo News. “Michael was a busboy at the Pyramid Club,” she wrote. “This is how I met him. We became good friends, and at times we were romantic.” Mallouk found that “no white journalist would cover” the murder, “so I went once a week to Peter Noel, of the Amsterdam News, a black newspaper, and updated him on the case.” She also helped organize the many benefits held in lower Manhattan for Stewart. But she had nothing to do with the Guggenheim exhibition. “I chose not to be involved in it,” Mallouk said.

In a recollection for a book associated with the Guggenheim exhibition, Goldberg writes that Basquiat at first did not want to address the killing “because he did not want to be political.” But he was plainly haunted by Stewart’s plight, ever aware of the fragile sense of security enjoyed by people of color. “It could have been me,” Basquiat would say of Stewart.

Nor was Basquiat the only artist to memorialize the slain student. Stewart was the inspiration for Radio Raheem, a benign neighborhood character killed by police officers in Spike Lee’s 1989 film “Do the Right Thing.” As that killing happens, during a violent confrontation between Bedford-Stuyvesant residents and police officers, one observer says, “They did it again, just like Michael Stewart.”

Asked if anything has changed since the young artist went down the subway-station stairwell at 14th Street, Mallouk was blunt. “No, nothing has changed,” she answered. “It breaks my heart.”

_____

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News:

Greta Thunberg: Powerful men 'want to silence' young climate activists

'I've never had a crystal': Marianne Williamson demands to be taken seriously

Trump tweeted ‘billions of dollars’ would be saved on military contracts. Th

Before a notorious phone call, the Trump administration was lauded for helping Ukraine