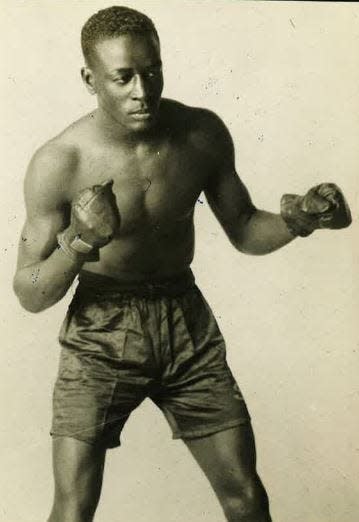

New Bedford's Suggs traded punches with some of the best known fighters of his era

Editor's note: Spotlight is the theme for the latest installment in the Buddy’s Best series, which kicked off last year and continues this summer. Former athletes, coaches and pioneers are among the people who will be highlighted.

Because he was good with his fists, Edward Murray Suggs planned a future around his hands. Boxing was merely the entry ramp to a route he hoped would lead to a career in the field of dentistry. At least that was the plan back in the early 1900s when the young man dubbed “Chick” was growing up in Newport, R.I.

Having left school in the eighth grade, Suggs hired himself out as a machinist’s apprentice and was working steadily in a local shop in his home city. Noon time was lunch — or break — time when some of the workers would stage impromptu boxing matches while others ate their lunch. Suggs was a regular among the punch throwers and always put on a show. He was so impressive in fact that a local boxing promoter took interest and signed him to fight a local boxer named Joe Azevedo in a sanctioned bout.

The prize?

Five bucks.

It wasn’t much of a match as both fighters clutched and grabbed their way through most of the rounds before Suggs was disqualified for throwing his opponent to the canvas.

Redemption, however, would come in his next bout when Suggs managed to stop his opponent (Young Melody) with a one-two combination. And when Chick knocked out Bob Boucher in the fourth round in his first fight at the Elm Rink in New Bedford, Suggs was on his way.

In 1917, Al Cassidy, matchmaker of the Union Athletic Association in New Bedford, welcomed Suggs to his stable. There was never any question about his physical skills and if there was anyone who questioned his integrity, Chick would answer that in his fight with Mickey Travers.

According to a story that appeared in the Sept.30, 1923 edition of The Evening Standard: “He (Suggs) had been signed to box Micky Travers in the old arena for $15 and his carfare from Newport,” the story said. “Before the bout the gambling ring approached Cassidy with offers of cash up to $200 to get Chick to dive. When he (Cassidy) refused they threatened and cajoled then went to see Suggs himself. They tried the same tactics on him but Chick just listened and didn’t say a word.”

His answer would come in the form of a reaction.

“When the fight started Travers was a heavy favorite to win by a knockout and according to the story “Travers beat Suggs quite badly in the first round. But in the second round Chick dropped him six times and finally put him down for the full count. Needless to say Cassidy and Suggs were mobbed by the would-be fixers when they left the club.”

But, Suggs fought on.

After turning 18, Chick married Elizabeth Spicer of Staten Island, N.Y. and shortly after, he retired his pick and shovel and left his job at the Coddington Point Naval Camp in Newport to accept a position as a private chauffeur in New York.

His boxing matches were few and far between for the next couple of years but when he returned to New England in 1921, Suggs met Dave Lumiansky, a well-known boxing manager who quickly lifted Chick from the ranks of the pork and beans fighter to the top of featherweight and bantamweight divisions in New England.

Many of his fights were at the Elm Rink in New Bedford, where Suggs would call home during the remainder of his boxing career. He traded punches with some of the best known fighters of his era and won New England championships in both divisions.

Name or reputation didn’t matter. Suggs took on all comers in his 11-year (1917-1927) boxing career including world champions Tony Canzoneri, Al Singor, Benny Bass and Bud Taylor. He also traded punches with such notables as Kid Chocolate, Babe Herman, Ray Miller and Sam Fuller, just to name a few.

According to newspaper accounts: “Suggs was the first Negro to fight a main bout in New York’s old Madison Square Garden.”

One of his most publicized fights came on Nov. 15, 1926 when Suggs lost the New England featherweight title to Dick “Honeyboy” Finnegan in a questionable decision before 13,000 howling fans at the Boston Arena. (The arena reportedly had a seating capacity of 9,000).

From all reports, the fight was a war.

The bout was billed as a world championship but was not universally recognized as such after champion Kid Kaplan could no longer make weight. So Finnegan had to be satisfied with fighting for the New England title.

Suggs reportedly dominated the early rounds but tired down the stretch and came out on the short end of a decision. When Mike Dundee stopped him in two rounds in Chicago on Nov. 19, 1929, Suggs called it a career.

He never did realize his dream of becoming a dentist and chose to work as a civilian employee at the Newport Naval Station in his later years. Throughout most of his sparkling boxing career, Suggs and his family lived in his adopted city of New Bedford, where he earned and maintained his reputation as one of the greatest boxers to represent the Whaling City.

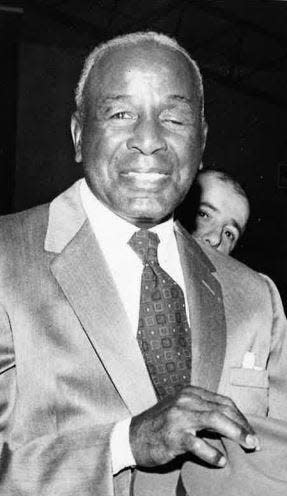

Suggs lived to be 74, passing away on Feb. 12, 1974.

This article originally appeared on Standard-Times: Suggs was one of the greatest boxers to represent New Bedford