COVID-19 antibody tests remain elusive in Canada

In March, a few days after returning home from Vancouver, I started feeling sick. First, it was sneezing and a runny nose, which lasted two days. Then my symptoms morphed into fatigue, aches, chest congestion, digestion issues and no appetite. It was a sickness I’d never experienced before, with a cycling of ailments that weren’t getting better or worse over time. By the fourth day, my sense of smell and taste were gone, despite no longer being congested. I consulted with Telehealth and an on-call doctor at my doctor’s office, who both advised me not to get tested for COVID-19 since I didn’t have any serious symptoms. Instead, I was told to stay home until I felt better. That didn’t happen for two weeks.

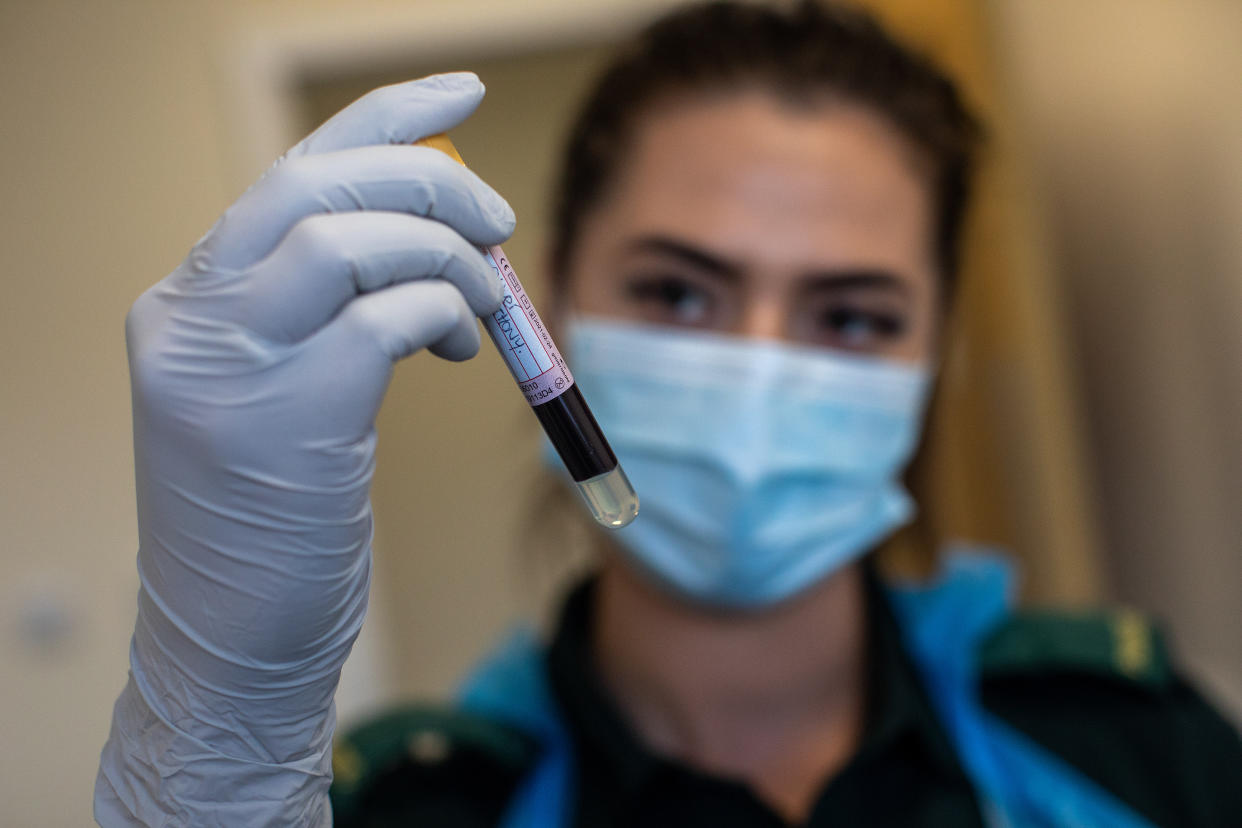

While I strongly suspect I had COVID-19, there’s not many ways to know for certain. When I learned in May that Canada had authorized the first COVID-19 serological tests, which can determine whether a person has antibodies against the virus, I was interested to learn more. I was eager to know where I could access these tests but when I spoke to my doctor, she told me she had little information. I recently went to a COVID-19 testing clinic to get swabbed since I was planning on spending time with my parents, who are seniors. When I asked the nurse who tested me if he knew anything about the antibody tests, he also told me he had no information, though he got asked about it regularly.

A spokeswoman for Health Canada said oversight of testing services falls within the jurisdiction of the provinces and territories. That means it’s up to the jurisdiction to determine whether the tests will be done in a clinic, a hospital or in public health settings, as well as the related fees, provincial fee coverage and supply and outsourcing.

Montreal announced earlier this month that antibody tests would soon be available for health care workers. In B.C., lab-based and point-of-care COVID-19 antibody testing kits are being used for research purposes only. A spokesperson for Ontario's Ministry of Health says the details around antibody testing, such when and where they can be accessed, are still being determined as further research is needed.

Getting a better picture of COVID-19 in Canada

In the meantime, a research study involving 10,000 Canadians will attempt to further understand COVID-19 and its impact on immunity.

Prabhat Jha, director of global health research at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, is leading the study. He says the objective of the research is to help inform public health authorities how many Canadians have been infected by the virus that causes COVID-19.

“The approach to do so that we’ve taken is to try and get as good a snapshot of the country as possible by trying to select people at random,” he tells Yahoo Canada.

Reachers teamed up with polling company Angus Reid to randomly select Canadians for the study, with the goal of oversampling people over the age of 60, since that’s the demographic most vulnerable to the virus.

Those taking part will fill out a questionnaire asking about COVID-19 symptoms and if they agree to the survey, they’ll be sent a blood kit from the lab. They aim to send out a total of 10,000 kits.

The kit will include a needle to puncture the ring finger in order to draw five drops of blood on a special paper, which is then dried and sent back to the lab. The test will then determine if the person is highly likely, somewhat likely or unlikely to have been infected.

“The tests still have a fair amount of uncertainty and we don’t want people to think the test is able to give them protection,” he says. “It’s not an immunity passport.”

The research will follow up with an online poll in a few months, then with a second test for samples of blood. That way they can determine how many people continue to test positive for the antibodies and how many people lose them. This information will give insight into predicting a second wave of infection, and help determine whether people who have antibodies have lower rates of subsequently testing positive.

“Then we have the ability to look at whether the antibodies are protecting you from fresh infection,” Jha says.

Learning how to learn more

Researchers are eager to get the study underway by July, since they believe the peak of the infection happened in mid-April. Antibodies typically kick in about a month after infection, and are believed to stick around for about a month or two. However, since so much is still unknown about COVID-19, that’s one aspect that Jha and his team are hoping to understand more about.

The research poll will use two different types of assays, which have yet to be chosen. Jha says it’s like the “wild west” when it comes to antibody tests available around the world, and their accuracy. There are reviews currently underway at different labs in Canada, England and Spain to determine which assay is most accurate. Jha suspects that in the near future, the tests will improve substantially.

“In a month, things will be a lot better,” he says. “Without the information from our study, we don’t know how to interpret an antibody test."

Jha says these assays have to be used prudently, even in a clinical setting, to make sure people don’t take it as a license that they’re hyper-immune. Just like if you have a flu one year, it doesn’t mean you’ll be immune to it next year.

“We’ll have to be careful that people don’t use (the tests) inappropriately and use them as immunity and just carry on,” he says. “We don’t know that yet.”