Anthony Miller was exonerated after 6 years in prison. Now every move feels like a gamble

Nov. 17, 2020: Don't linger too long

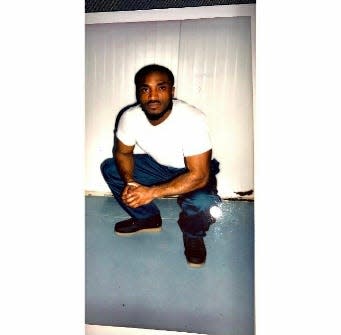

Anthony Miller is free from prison. The quaint city block of Bradburn Street where he walks is calm and friendly, far from his former cell. As cars pull in and out of driveways, residents greet Miller as if he were family. He points to a half dozen homes while discussing childhood memories.

"It used to be normal for me to be out here," Miller said, gazing down the street. "Hanging, playing basketball, cooking out, or getting ready to go somewhere."

The world he returns to is in the thick of a global pandemic and a renewed social-justice movement fighting for police reform. As the country deals with those complex challenges, Anthony copes with the reality that his youth has vanished in the six years he spent behind bars for a crime he didn't commit.

Once a dreamer, his goals have changed. Happiness is now attached to life's simpler pleasures.

When Anthony recollects life behind bars — nights with friends at the casino felt like perfect opportunities for fun now that he's a free man. Instead, he finds himself isolated and in a constant state of paranoia.

Like the casinos he patronizes, every move feels like a gamble. Everything from the clothes he wears to driving with a hooded sweatshirt on is examined. He bypasses certain stores or specific neighborhoods. Lingering anywhere with anyone for too long is triggering.

Sept. 25, 2013: False identification

Miller was 21 years old when he was arrested.

"I got up at around 6 a.m. and got ready to put my little sister on the school bus. What was different about this morning was when I woke up, I got on my knees and said a prayer. I asked God not to give me anything I couldn't handle."

That morning, he had an interview for a warehouse job. His dream, though, was to make it big as a rap music producer, and he spent most of his free time in a garage, crafting creative endeavors with his friends.

After the job interview, he went home. He got a phone call while he was playing video games.

Someone he knew had been attacked on Bradburn Street, a popular meeting place for Miller and his friends.

According to police reports and trial testimony, Miller met up with Aaron Hinds on Bradburn Street at about 7:30 p.m. They stood outside in a driveway, trying to sort out what happened to their friend.

At 8 p.m, a half-mile away on Roslyn Street, Jack Moseley was robbed at gunpoint. An assailant took Moseley's iPhone, cash, and a pack of cigarettes.

The Rochester Police Department began its search. Around 7 minutes later, police officer Daryl Hogg spotted Miller and Hinds on Bradburn Street.

"That's when they told us we matched the description of robbery suspects," Anthony Miller said.

Moseley, the crime victim, had told 911 dispatchers that the gunman was a 5-foot-9-inch, young Black man wearing a gray hooded sweatshirt and blue jeans.

Miller was 4 inches shorter. His hoodie was red. His pants were black. But his skin color matched.

Hogg and Daniel Watson, another Rochester police officer, frisked Miller and Hinds. The officers found none of the items Moseley said were stolen.

Despite the lack of evidence, Miller and Hinds were taken into custody. As they sat in the back of a patrol car, a police dog followed the scent of the alleged gunman to Genesee Street — several blocks south of Bradburn Street.

The police officers drove Miller and Hinds to Moseley. He identified Miller as the gunman even though Anthony did not fit the description given during the 911 call, stating that Miller must have changed his clothes. Anthony was put in handcuffs. Hinds was accused of being a lookout but was not arrested.

Inaccurate witness identification contributed to 784 of the 2,783 cases in the National Registry of Exonerations. Of those 784 cases, 508 wrongfully convicted people were Black — two-thirds of all cases.

Jack Moseley's eyewitness testimony changed the course of Miller's life.

Assuming wholeheartedly that his innocence would set him free, Miller decided to go with a public defender for his case. He also rejected a plea deal of 3 1/2 years, believing jail time would hinder his pursuit of a career in music production.

At trial, a jury convicted Miller of first-degree armed robbery. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Working toward justice

It felt surreal when Anthony arrived at Elmira Correctional Facility, a maximum-security state prison in Chemung County.

Over the next 3-4 years, Miller spent the maximum time allowed in the prison's law library with the mission of educating himself on the justice system. He researched similar cases and reached out to lawyers and grassroots organizations to advocate for his release.

He filed motions and contacted news organizations to create awareness around his story. The pursuit of justice kept him busy, making his lengthy sentence somewhat bearable.

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, innocent Black people spend an average of 13.8 years wrongly imprisoned before being exonerated — about 45% longer than innocent whites.

A childhood with ups and downs

Miller mentions his father a lot in conversations. He is quick to combat the stereotype that his incarceration stemmed from a fatherless childhood. Miller is candid about his youth — an imperfect past he doesn't avoid.

"My parents have been together 37 years," Miller said. "My upbringing was good. There was always food in the refrigerator. I didn't even realize we were on Section 8 until I got older."

Anthony was a regular kid, riding bikes and playing football with his friends. But once his boyhood dream of going to the NFL faded, he began to act up for reasons he can't explain to this day.

"I can't say that I was the kid that started selling drugs at 13, 14 years old because my dad went to jail," Miller said. "There was no significant event in my life where I can say that's where things went bad. I was a normal child."

Nevertheless, 17-year-old Anthony dropped out of high school in the 11th grade. Suddenly, indifference led to youthful desires overcoming his psyche as money, and material possessions became his motivation.

Ultimately, bad decision-making led to Miller pleading guilty to misdemeanor charges which landed him in a juvenile detention center for 60 days.

"My father had no idea what I was doing. When I was out in the streets, he thought I was playing basketball," Miller said. "I sat back and really thought about my life. I couldn't go out like that -- going to jail. That's when I decided to change my thoughts."

When Anthony Miller was released, he attained a GED. A year later, he attended Monroe Community College, studying liberal arts.

Seemingly back on the right track, Miller worked multiple temp jobs and developed a love for rap music production, a career path he believed was his destiny. He and his friends got serious about the pursuit and dedicated their time to the craft. He avoided his old routines and stayed clear of Bradburn Street for months.

Nolan Wengert was one of the officers that arrested teenage Miller.

Years later, Wengert, an RPD veteran, was the lead investigator on the scene of the Roslyn Street robbery.

Miller said that link sealed his fate and ended his redemption story.

"Everybody has a past," Miller said. "But that shouldn't be evidence of my guilt. To the system, I'm just a criminal."

Nolan Wengert was named the Rochester police department's Investigator of the Year in 2015. He died in 2017. But available public records provide insight into the investigation he led.

According to an RPD case file, two days later, while Anthony was in jail, Wengert used a serial number provided by the victim to track the stolen iPhone.

The GPS signaled him to Genesee Street and W. High Terrace, where a group of 30 people fled after the phone's alarm was activated by police.

According to court papers in Miller's lawsuit against New York, the last GPS hit on the phone indicated it was at an unknown location on Stratford Street. Investigator Wengert never received any other updates regarding the tracking of the phone. While Anthony sat in jail, Jack Moseley received three emails from Apple regarding his stolen phone's "Find My iPhone" application.

Anthony was never found to possess the stolen phone.

Empty promises

Still trapped behind prison bars, Miller's calls, letters, and proclamations of innocence elicited nothing but empty promises.

As the years began to add up, frustration took over.

"It was hard hearing it in his voice," Troy Frierson, a longtime friend of Miller from Bradburn Street, said. "We would talk all the time. He was tired of sitting -- crying out and nothing happening."

"When it came to the justice system, I was so lost," Miller said. "It's harder to get justice after you've been convicted because the burden is on you."

In spring 2019, Monroe County District Attorney Sandra Doorley created the Conviction Integrity Unit to review claims of innocence on behalf of defendants.

After learning that the unit decided to review his case, Miller assumed it was finally his time to be acquitted.

In an October 2020 email to Doorley, Monroe County District Attorney's Office Chief Investigator Charles Dominic stated that he interviewed various people and examined several documents on Miller's case.

"I can't exonerate him from a timeline standpoint because he could have been there," Dominic wrote.

Dominic writes about his concerns over Anthony's alibi, about Hinds (who was with Miller when he was arrested) never being questioned the night of the crime or called to testify at trial.

Aaron Hinds was prevented from testifying at Anthony's criminal trial because Miller's defense attorney failed to timely file a notice of alibi, and the motion was denied.

Investigator Dominic accuses Miller's parents of being uncooperative in his investigation, citing failed attempts to meet in person.

"The parents' silence speaks volumes to me," Dominic writes. "I think their message is loud and clear!!"

Anthony firmly rebuts this claim.

"This could potentially free their son," Miller said. "My parents were fully cooperative."

Miller's case was closed again, but his will was unflappable.

"I was innocent," Miller said. "I kept fighting, filing 440 motions,"

A 440 motion is a New York post-conviction law that allows a defendant to ask the court to vacate a judgment against them or re-open the case.

On Nov. 13, 2020, 17 days after the Appellate Division, Fourth Department heard an oral argument, they decided on Anthony's case. According to Elliot Shields, Miller's current attorney in his lawsuit against the state, the speed of the ruling is unheard of.

"It thoroughly placed blame on the police and the prosecutors," Shields said.

The Fourth Department stated in part:

"There is considerable objective evidence supporting the defendant's innocence. The defendant was found standing in a driveway half a mile from the crime scene only seven minutes after it occurred, wearing clothing different from the clothing worn by the gunman. He was not in possession of the fruits of the crime or of a firearm."

Four days later, Miller was a free man.

Starting over during a pandemic

Eight months free, Anthony Miller is experiencing the challenge of restarting his life. Within his thoughts, the line between blessing and bitterness is razor-thin.

"I'm working on getting an apartment and getting my first car at 29 years old," Miller said . "It's times like that when I think about the six-and-a-half years stolen from me."

Time is now precious to Miller. His movement is minimal, and his circle of friends is kept small. He mentally prepares himself for various scenarios when people want to hang out. The ability to live in the moment has dissolved. Instead, every minute is defined by the perils of his past or his plans for the future.

As weeks turn to months, Miller approaches the anniversary of the day he was set free.

When his new journey started, he disclosed his need to play things safe and his caution with being in particular places and wearing certain things. But the more time he spends in his new reality, the less he wants to conform.

While preparing to visit his lawyer downtown, Miller's father suggested wearing a shirt and tie. His retort was rebellious.

A system that failed

Troy Frierson and Anthony Miller are still good friends, hanging out at the gym instead of basketball games on Bradburn Street. While working out at LA Fitness, Frierson notices Miller's evolution.

"He's wiser," Frierson said. "You can just tell by the way he talks now."

When news of injustice breaks, Anthony finds himself increasingly immersed in discussions. Fighting for social change was a trait Miller always believed he possessed, but now it's heightened by his experiences.

"I'm definitely more emotionally invested because I've dealt with the system," Miller said.

Most of the attention given to police reform revolves around the shooting of unarmed people of color, but Anthony hopes betterment also involves those with stories similar to his own.

Miller has filed a lawsuit against the state for his wrongful conviction. In New York, those who show credible evidence of their innocence can collect damages.

"The first young Black man they encountered on the street, they stopped," said Elliot Shields, the lawyer representing Miller in the lawsuit.

According to court documents, Anthony was the first Black man confronted by Rochester police after the victim's call to 911.

"It could have been anyone in Rochester," Shields said.

The most important thing for Miller is that those who are responsible for his imprisonment are held accountable.

"Without accountability, the system will remain unjust," Miller said.

From Miller's vantage point, the entire system failed him. The police, the prosecutors, the District Attorney's Office, his trial lawyer, the jury and the man who identified him.

According to the Innocence Project, a nonprofit legal organization committed to exonerating individuals who have been wrongly convicted, mistaken eyewitness identifications contributed to approximately 69% of the more than 375 wrongful convictions in the United States overturned by post-conviction DNA evidence.

A dream deferred

Stories like Miller's tend to come with the revelation of a silver lining at some point.

While Miller concedes that he doesn't know how Sept. 25, 2013, would have turned out had the rage for his friend's attack not been interrupted by his arrest, he declares that there is no silver lining in his story and that he is not better after serving six-and-a-half years in prison.

Miller hopes he can just be himself without being judged in the future, which is a modest desire amid challenging times.

One question does remain. Would Anthony still leave the house after receiving that phone call if he could relive that day?

Anthony's music producer aspirations have faded and been replaced with an urge to attain a sense of normalcy: a stable job and a family to call his own. He believes the only crime committed in his case was the theft of his dreams.

Contact Robert Bell at: rlbell@gannett.com. Follow him on Twitter: @byrobbell & Instagram: @byrobbell

This coverage is only possible with support from our readers.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: Anthony Miller Rochester man exoneration rebuilds life false identification