Along with police reform, America needs to fix its broken parole system

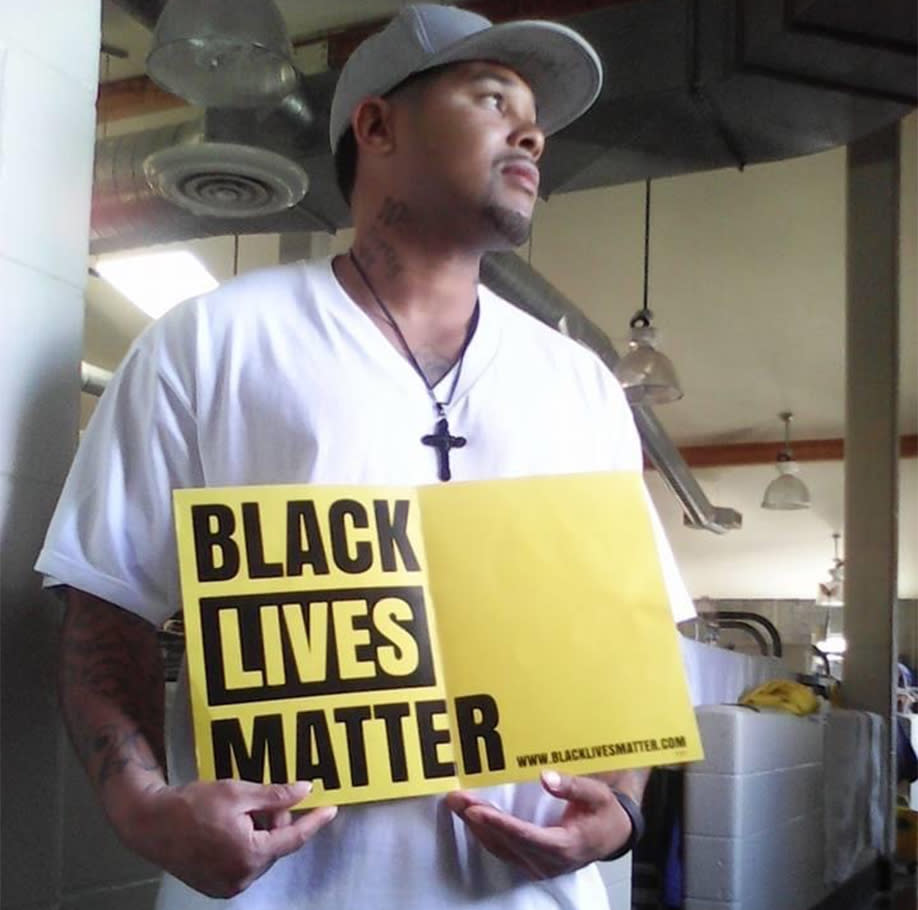

As America struggles to figure out how to fix systemic racism in police departments following the killing of George Floyd, we must also acknowledge that our country’s entire criminal justice system needs to be reformed. After all, while the United States represents about 4.4 percent of the world’s population, it houses around 25 percent of its incarcerated. Forty percent of those behind bars are African-Americans, who make up just 13 percent of the U.S. population. Another way of looking at the stark, discriminatory efficiency of the American model is that the system is working exactly how it was designed to, as a business, as my own story illustrates.

On Sept. 25, 2018, I was paroled from San Quentin State Prison after serving 13 years for assault with a deadly weapon. I grew up in California’s Central Valley, mostly in a small town called Tulare. I entered foster care when I was 8 years old and was passed around often between group and foster homes. The feeling of being disposable was real for me at a young age. I always had a challenging relationship with my birth mother, and my father passed away before I really got a chance to know him.

My world was not molded from opportunity and access, but from unprocessed trauma, abandonment and neglect. When I was 11, my best friend was murdered right in front of me. I still remember that moment vividly, the feeling of losing what little trust I had in the world. I joined a gang that same year because, though they might not have had the tools I needed to process things, at least they could relate to the pain I felt. Without proper guidance, I navigated the world I lived in to the best of my abilities. By my senior year I became a father, and soon after high school I had my second child. I told myself at that time I would do whatever it took to protect them from the world that left me so vulnerable.

So when I learned that my 8-month-old daughter had been sexually molested, I lost it and decided to take justice into my own hands. I tracked down the man who had done it and shot him in the leg. Seven days later the police arrested me at my home. I was charged with attempted murder and went to trial, where I was judged by 12 of my “peers” who didn’t know any of my life story, just what was written in the police report. I was found guilty of a lesser charge — assault with great bodily injury — and was sentenced to 14 years in prison.

I spent the first few years in prison projecting my anger with my life onto anyone and everyone. Then, in 2014, something interesting happened to me. I joined a computer coding program run by the Last Mile, a San Francisco nonprofit. Crazy thing is, I didn’t even know what coding was before this program. I didn’t grow up with a computer, let alone an understanding that people got paid to code them. I thought the program meant I’d play solitaire for a couple of months and then quit.

But then I realized I was good at coding and it was another way for me to articulate my thinking. I struggle with reading a lot. I read my first book in prison, but our classroom facilitator printed code out for me to read so I didn’t have the challenge of all the technical jargon. We had this MIT graduate who came in and asked us to build an algorithm that could solve sudoku puzzles. He gave us 72 hours. I was able to do it in 48 hours.

Belief is a powerful agent of change, and the founders of the coding program started saying they believed in me. For the first time in my life, someone told me I didn’t have to be defined by my current situation. That ignited a thirst to learn, explore and be curious. I began to question things, starting with my own situation. I had also enrolled in the Prison University Project, the only college program in California that offers an associate’s degree to the incarcerated, and studied business, philosophy and psychology while I continued to learn coding.

Finally I connected with some family on my father’s side and started to learn about him. To my surprise, I found out that he came to the U.S. from Samoa on a computer science scholarship. The one thing that he left me was the one thing that I love doing. So when I sit in front of my computer I don’t just connect to the internet, I connect to my father.

As I continued with the coding program, I met a filmmaker named Bradley Smith, from Google, who made a short documentary about my story. Three weeks before I was paroled, I signed a work agreement to start as a software developer with a tech company in San Francisco, which I started a month after my release. Coding gave me my first real opportunity in life, and when I was released from prison I began my parole in Oakland.

I was surrounded by some beautiful people who taught me the difference between transactional love and unconditional love. One of those people eventually became my wife, and I felt like my life was starting to come together. But the system didn’t recognize any of my growth or progress. It treated my situation as if I was stagnant and didn’t have anything going for myself. To this day, I am still at the mercy of the system that isn’t on my side. The conditions of my parole specify that I can’t leave a 50-mile radius from my doorstep without permission. That greatly limits my advancement opportunities, such as when I had a chance to join a team from Stanford University that was building technology for the reentry space. Because of the travel restrictions, I had to remove myself from consideration. Even when permission to travel is granted, I have to get a further written OK to stay overnight, and I have to ask at least 10 days in advance, which means no spontaneous dates with my partner or unexpected life events.

Another condition of my parole was that I was required to take anger management classes, even though I had already completed them when I was still behind bars. In fact, I got certified as an instructor for the course and taught it to other incarcerated folks. Yet after my release I was forced to take it a second time, and there’s no arguing about it unless you want to be cited for a violation and risk being sent back to prison.

As my situation came into focus, I found myself asking why things are like this. The more I started looking for answers, the more I realized it had to do with a system designed to make money off the formerly incarcerated. The system is a business, and what it’s selling to society is the feeling of protection. When programs like anger management or domestic violence are run by the state, parole gets more funding for every person enrolled, which means there is an incentive to fill classes regardless of whether they will help those they are intended to.

The same system criminalized me before I had committed any crime, and looked to turn a profit. While society largely turns a blind eye to the crimes committed by those of privilege, it scapegoats the communities like the one I come from, keeping their population underserved. My community is overpoliced and demonized by society.

Institutionalized racism has perpetuated unconscious biases against people who look like me and against communities that look like mine. What is normal in my neighborhood is not accepted by mainstream society. For example, Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS, for short) is a risk assessment that is used by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to measure the threat of an individual while they are incarcerated. Each incarcerated person receives an assessment score, and it follows you even when you are paroled. The software for assessment cost the CDCR a lot of money to implement and use, but what disturbs me most is the data it generates based on roughly 100 questions about your upbringing. Has anyone in your family been arrested, been involved in gangs or drugs? There’s a vicious cycle at work here. Information about the community I was born into is used against me when the risk I may pose to society in the future is assessed. With COMPAS, the theory is that anyone who grows up in a poor or underserved community is a threat for the rest of their life, and state and federal resources are based upon that conclusion.

Believe me, after spending years in jail, it’s hard enough adjusting to civilian life. You have to deal with managing your own expectations and those of others, reestablishing relationships with family and friends. The triggers that result from incarceration are everywhere, such as anxiety from loud noises, keys jingling or lights shining in your eyes. My body still becomes alert at 4 p.m. every day from being conditioned to stand for count.

I had naively thought parole was there to assist with job placement, housing or mental health services. Instead, I find it hinders me from regaining my humanity and starting a normal family life. My wife and I are subject to random searches of my vehicle or our household. I have to plan around my parole officer’s schedule, and simple things like not answering his phone call can be seen as an attempt to go AWOL, which is grounds for a violation. When I successfully complete parole it will not be because of anything it has assisted me with, yet countless resources and funding are being poured into this system, like oil into an engine. If money, volunteerism and resources are going to be brought into this space, then it should be to actually assist people to get their lives back on track. Yes, I made mistakes and bad decisions in life that I learned and grew from, like any human being, but completing parole in its current version does not make society safer. It would be wiser to create a system that gives people leaving prison the tools to cope, process trauma, establish healthy relationships within a community and obtain marketable skills. We should get rid of the for-profit business plans of these systems that are designed to oppress. Instead, we should invest in people who suffer from an upbringing marred by poverty and neglect, and recognize that that doesn’t have to be the end of the story.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: