Aeon Station: ‘This is the story of how not to do it’

There’s a reason why one of this year’s very best releases sounds a little old-fashioned: it’s that it is, at least in part, the follow-up to one made back at the dawn of the new millennium. Observatory, by Aeon Station, is a big, bruised record of indie rock, both anthemic and melancholy. Guitars fuzz and roar; ballads burn and wane. It’s an album through which male relationships and loss run deep – in this case, the loss of the singer’s father nearly 20 years ago – but that’s how long it has taken some of these songs to surface. And it comes shrouded in another kind of separation, too; that of its maker from the man who was his band mate for three decades.

To get to Observatory, one has to rewind to the last century. To New Jersey, where a little indie band called The Wrens made two albums in the mid-Nineties that won them major-label interest – they never signed a deal – and a handful of fans. Battered by their experiences, it took them six years to make a third, The Meadowlands, released in 2003 on the tiny Absolutely Kosher label. It was made by four men on the cusp of middle age who felt as though they had been trying to get noticed for ever. It was battered and desperate; sometimes its tracks sounded degraded, as though the master tapes were eroding as they were recording; sometimes they sounded euphoric, but with an air of manic desperation.

Probably no one would have noticed The Meadowlands either, had one of those few Wrens fans not been a young man from Minnesota called Ryan Schreiber, who had set up an album reviews website in 1995. By 2003 his website, Pitchfork, had become hugely influential within independent music, and when Schreiber gave a rave review to The Meadowlands – rating it 9.5 out of 10 – suddenly The Wrens got noticed. They were able to sell out shows, play in Europe, and were covered in The New York Times. A young Canadian band called Arcade Fire was listening, and realised they too could explore the combination of scale and intimacy that was The Meadowlands’ trademark. And everyone waited to see what The Wrens would do next.

The Wrens duly started recording, though not until 2010. And then they didn’t stop. It seemed as though every year was going to be the one in which the sequel to The Meadowlands came out; the American writer Steven Hyden called it “the Chinese Democracy of indie rock albums”. But unlike the epically delayed Guns N’ Roses album, The Wrens’ next masterstroke never came out, even though they had signed to Sub Pop to release it.

For four or so years, the band’s two driving forces – singer/bassist Kevin Whelan and singer/guitarist Charles Bissell – would write their songs separately, recording them skeletally at home, then come together to alter them, improve them, make them Wrens, bringing the other members – drummer Jerry MacDonald and guitarist Greg Whelan, Kevin’s brother – to record their parts as and when needed. Never was the four-piece band together in one studio. Still, by 2014, a very early version of the record was being taken to labels, and Sub Pop signed the band later that year. But still nothing happened. The years passed and still there was no sign.

Finally, earlier this autumn, Whelan announced he’d had enough of waiting for Bissell to be done with his half of the album. Whelan’s songs for The Wrens – recorded the best part of a decade ago – were going to come out, along with some new ones, under the name of Aeon Station.

“I had lost music. I had lost my way. I just wanted to get back,” Whelan says, speaking from his suburban New Jersey home, so early it’s still dark outside. Eventually, he began to make some new songs. “I really hadn’t done any music since 2013. I started recording and writing last fall. It was just for my own enjoyment, not with this master plan. I believed there was always going to be a Wrens record. No one believed it more than me. My wife and my friends would be saying, ‘You’re stupid.’ But I never didn’t believe it, because I wanted that. It was all I ever wanted.”

Then this year began, again, with Bissell publicly saying – as he had before – that there would be a new Wrens album in 2021. This time, Whelan didn’t believe it, even if he still lets himself cling to the notion The Wrens can still be a band.. “I’d had it. I told them, ‘If we don’t do this by this date, I am finally going to move along. I am not moving away. I am not breaking up the band. I love the band. But I want to enjoy music and have fun doing music.’ That was in March of this year. But it wasn’t that I’m not in the band. I want to be in the band, and until we can figure out our stuff, I am going to do music. I am not going to sit in my room and hope and pray and wait.”

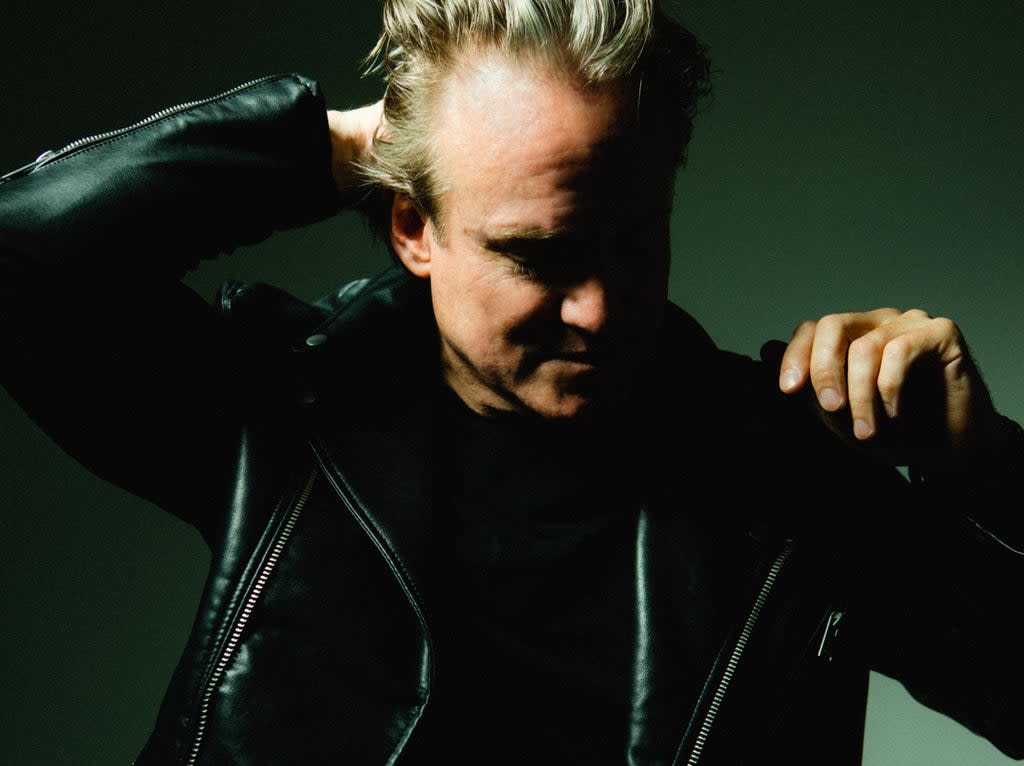

When you lose your way, how do you get it back?

Kevin Whelan

Whelan’s 51 now, a married father of two kids. Much of the music on Observatory was born when he was a different man. He recorded his first demos in 2007, already four years after The Meadowlands, an eternity in independent music. “It definitely has a theme,” he says, “because it was written in my late thirties. And I think when people go through their forties, it’s like a minefield. My wife and I got married; we had two kids. I’d lost my job. We moved to Asia. I think the theme is around life really being complicated, and how you keep passion, and commitment through tough times and not lose your way. When you lose your way, how do you get it back? It’s all those themes, but it’s a positive one; it’s not a negative one. We get beat up enough, day to day.”

He says he had his five Wrens songs completed – recorded, mixed, ready to go – eight years ago. “The ones you hear on Observatory were truly completed in 2013. Not moved. They’re little statues, for better or worse. All that music was recorded in my basement with one amplifier, one microphone. It was DIY, as we always were. Unfortunately, my partner has a bigger process. So he worked on his, and that was Chinese Democracy.”

In the end, something had to give. “I was very upfront. I was saying every option is on the table. Everything. We could scratch the record and go and make a new punk rock record. We could do everything. The only thing I could no longer do was wait. I could no longer believe it was going to be finished.”

That’s not quite how Bissell remembers it. To find out that “a separate solo album was already being worked on and arranged for release in secret” was, he says in an 8,000-word email that itself prefigures a 40-minute Zoom conversation, was, “goddamn – yes, a surprise”.

These days, though Whelan says The Wrens can still be a band, Bissell insists not. “That will never happen, given a finite universe.” They haven’t communicated for months now, but for years the two of them were inseparable. As a young band, the four members shared a house. The other two moved out, but Whelan and Bissell lived together for 15 years, before each married. You can hear the bond they had in the way they talk about each other’s music. For all his anger, Bissell says of Whelan: “He is an effortlessly good singer.. He is literally Sinatra-like in his ability to sing it, from the top, two or three times and have it be great all three.” Whelan says of Bissell’s unreleased songs: “They’re very very good. They’re great.”

That his and Whelans’s songs are not being released together as a Wrens record is quite evidently heartbreaking to Bissell. When I contact him, he says it will force him to finally address what has happened – he spoke only briefly to The New York Times for a long piece it ran about Whelan in September – and to set out how he feels. Which, in short, is sold out.

He’s especially aggrieved about a narrative that paints him as the Axl Rose of the story, the obsessive, delaying, temperamental one (“as if I had somehow held him/them back, intentionally or at least thoughtlessly and selfishly even, which I’ve gotta say, was really confusing and weird,” he wrote in his email). He says his music is done – and sends me not just his eight songs for The Wrens’ album but the others he has written to complete his own album.

“Our definitions of done are different,” Whelan had told me. “My definition is that it is written, recorded, mixed, mastered and it’s not in my house.” And, it should be said, Bissell’s tracks arrive unmixed and unmastered – though that can be fixed quickly – but the best of them are astounding.

And, Bissell says, for all Whelan’s insistence his work was done years ago, that’s just not the case. He still had little dabs of polish to apply as late as 2019, just as Bissell did. He says the album was, to all intents and purposes, ready by 2019, but the problem was that relations within the band deteriorated catastrophically over the following year, so that by the start of this year he was resigned to The Wrens’ album coming out posthumously.

“It would’ve been a great way to go out on a high note,” says Bissell. “It would be the first time we’d be putting out a Wrens record on a big label; it would enable him or any of us to then go from there and do whatever solo thing they cared to, with real momentum behind them.” (He notes that by the time he gets round to releasing his music, The Wrens’ story will have been told, and there’ll be no New York Times feature for him.)

But Bissell’s biggest bone of contention is that Whelan never told him what he was going to do. He says there was no warning in March and that he only found out in June, when he called Sub Pop to talk about The Wrens’ future, or lack of one, and the need to discuss what to do about the music.

“And they told me – and this is for me, the classic moment in this whole thing – ‘Oh, well we already have a release date for Kevin’s record,’ which was one of those moments when, if this was an early-aughts [noughties] indie film, the camera would’ve done that telescoping dolly zoom thing to show the character’s world inverting.”

All the problems that beset The Wrens lie in the failure of their first two albums, Silver and Secaucus, between 1995 and 1997. The band didn’t get popular enough to justify keeping at it full time and so they took on day jobs. And it turned out they were good at their jobs, and the jobs got serious – the reason Whelan has to do interviews before work is that he’s the global head of R&D, strategic initiatives and operations at the pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson. The jobs, the family commitments – in short, the adulthood – meant The Meadowlands itself took an eternity to record, in bits and pieces in their home studio, overseen by Bissell.

They were all pushing middle age by the time it came out, and with more commitments in their lives, and they weren’t going to become a 200-nights-on-the-road band. So rather than get back to recording straight away, they spent several years promoting it as best they could around their work – flying to England for a weekend to play a London show, for example (they were an extraordinary, incendiary live band, one of the best I have ever seen), but it was always part-time.

“Those three guys had very serious careers,” Bissell says, “which were going better and better, and then a couple of weekends a month – like Army Reserve – they get to go play this show where people clap for you and buy your merch and you make extra money on the side. It was pretty nice. And we’d been a band for pushing 20 years. So it became easy to coast along and years start to go by.”

If Bissell makes The Wrens seem like a holiday from real life, Whelan points out how arduous it could be: to play Europe, the band would fly over at the end of the working week, do a Saturday night show and fly home, so as not to miss work. “At the height of it, the best days of the best year, we were making $,7000 a show,” he says. “Between four men in their late thirties with families, what are you gonna do with that?”

The sheer effort made things take longer. “That absolutely is a part of it,” Whelan continues, “and also, you don’t want to do s****y work. But I also think that obstacle of having [another] life helped the art. There was no expectation. The pressure was just: why are you doing this when you have a full-time job and a family, and a special needs kid, but you still do it?”

I think the obstacle of having another life helped the art

Kevin Whelan

By the time they came to follow up The Meadowlands, their lives were even deeper into adulthood (Bissell lost his job in the accounts department of an advertising firm – a job Whelan had found for him – for spending too much time attending to Wrens activity, but he became the main carer to his kids). So it wasn’t just that Bissell was taking forever, it was that everything was hard to organise. Bissell says he would have been happier with a much more direct way of working, getting the band together to record live, instead of their patchwork of individual home recording.

That was impossible, though, he says. “I live in Brooklyn, Greg’s in south Jersey, Kevin’s in central Jersey, Jerry’s outside of Philadelphia. That would mean organising a central rehearsal place, because I’m not doing it in a basement. I’m not going to fix the PA. If we’re incredibly on top of our game and can assemble one song every two get-togethers, to album level quality, for an album of 10 songs, that’s 20 rehearsals plus studio time. You’re committing to driving two hours a time, 20 to 40 times over the next year. There’s real nuts and bolts involved in all of this.”

Then you have to add in all the extraneous things that come with ageing. Health problems, for example: Bissell, now 57, notes he has just finished five years of treatment for cancer, and has had mental health issues as well. It’s just not like being 25 with all the time and all the energy in the world to spare.

And so here we are. Now, the good news for music fans is that two stellar albums will emerge from all of this, first Aeon Station, then Bissell’s when his own record also comes out on Sub Pop. Both are aware of the unimportance of their travails in the wider world – indie rock band who haven’t released anything for years have broken up – but both are equally wrapped in the personal tragedy of something that partly defined both of their lives falling apart.

“Isn’t it f***ed up?” Whelan says. “This is a story of how not to do it. If you really want The Dummies’ Guide To Rock, you don’t do it our way. We’re the case study in the bubble in the corner of the page.”

‘Observatory’ is released on Sub Pop on 10 December

Read More

Adele review, 30: Patron saint of heartbreak licks her wounds in a divorce album that takes risks

From SwiftTok to #Taylurking: How Taylor Swift redefined online fandom

‘It’s brutal out here’: How Olivia Rodrigo’s acerbic pop speaks for an anxious generation

Robert Plant and Alison Krauss: ‘When we get it right… we just look at each other and laugh’