80 years later, 'Citizen Kane' is still the greatest (and Oscar frontrunner 'Mank' helps prove it)

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

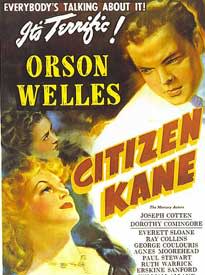

"Citizen Kane," which celebrates its 80th birthday May 1, is the Muhammad Ali of movies. The Greatest.

You can argue otherwise — just as you can argue that Lincoln isn't the greatest president, "War and Peace" isn't the greatest novel, Billie Holiday isn't the greatest jazz singer. People do.

But it doesn't make the film loom any less large. Attempts to de-throne it make news from time to time: as when a 2012 "10 Best Movies" poll from Sight & Sound magazine bumped "Citizen Kane," the traditional champion, to the No. 2 slot, and gave Hitchcock's "Vertigo" the crown. It caused talk, briefly.

But the stature, even now, of Orson Welles' 1941 classic is indicated by the fact that "Mank," the drama about the writing of "Citizen Kane" that led this year's pack of Oscar nominees — 10 nods, including best picture (the awards telecast is 8 p.m. Sunday on ABC) — isn't even the first movie made about the making of "Citizen Kane." It isn't even the second.

Which film deserves best picture?: We passionately defend all eight Oscar contenders

'Mank' review: Netflix's excellent 'Citizen Kane' origin story isn't just for film nerds

"The Battle Over Citizen Kane," a 1996 documentary, and "RKO 281," a 1999 HBO film, both covered this ground earlier. Pretty thoroughly, you might think. But it wasn't enough.

It didn't curb the appetite for more about "boy genius" filmmaker Orson Welles, about William Randolph Hearst, the powerful media mogul whose anger he dared by making a thinly-disguised biopic, and Herman J. Mankiewicz — "Mank"— the outrageous, sozzled screenwriter who was caught in the crossfire (played in the new film by Gary Oldman).

The making of "Citizen Kane" is one of the greatest stories about the movies. But no one would want to tell it, if "Citizen Kane" didn't also happen to be the greatest movie.

What makes it so? There are a lot of ways to answer that question. But one is to simply say that it is the moviest movie.

It's the film that celebrates, more than any other, the medium itself. It's a love letter to the movies — everything they are, everything they can do.

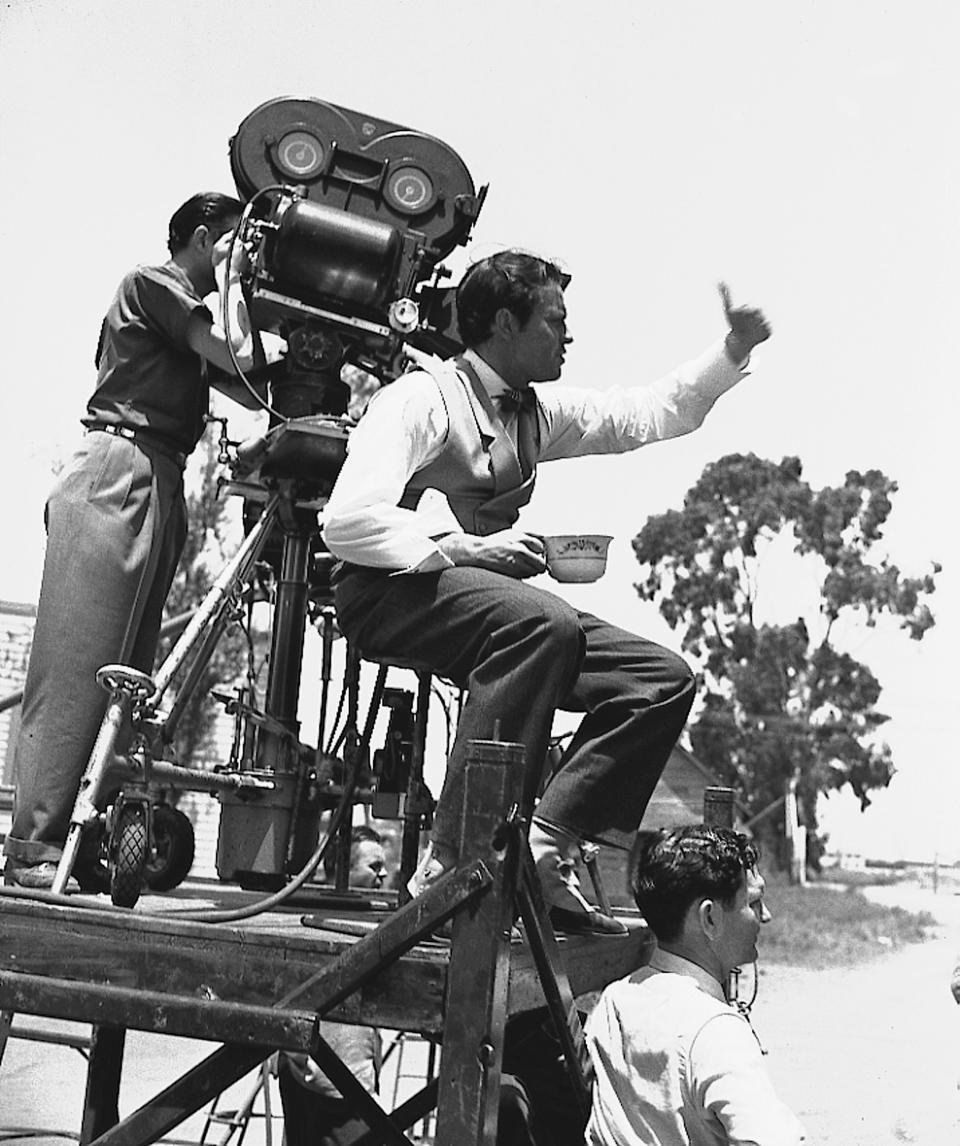

Orson Welles — all of 26 when "Citizen Kane" premiered — had already made a huge name for himself by pushing theater and radio to their limits. On stage, he had set "Julius Caesar" in fascist Italy and cast a Haitian "Macbeth" with African-American actors — commonplace ideas, now, but jaw-dropping to 1930s audiences. His experiments in making radio more vivid had reached a notorious climax when his 1938 "War of the Worlds" broadcast convinced a lot of listeners that squid-tentacled beings from the planet Mars had actually invaded Earth.

So when Welles arrived in Hollywood — given unheard-of carte blanche by RKO studios, who were desperate for a hit — it naturally followed that he would be making The Ultimate Movie.

He went into it with his usual gusto. "A movie studio is the best electric train set a boy ever had," he memorably said.

His Ultimate Movie would have everything in it — all he'd learned about staging from the theater, all he'd learned about sound from the radio, all that directors on multiple continents had learned, over 40 years, about making movies.

Historians fact-check 'Mank': Who really wrote 'Citizen Kane?' And does 'Rosebud' have a hidden meaning?

Oscar predictions: Who will win Sunday's Academy Awards – and who should

From Germany, he borrowed expressionism: grim gothic sets, shadowy lighting, dollying cameras and odd camera angles (he famously gave his sets ceilings, and shot up from the floor so they would be visible).

From the Soviet Union, he borrowed montage: the quick, nervy editing in such sequences as Susan Alexander's (Dorothy Comingore's) succession of disastrous opera performances.

From American filmmakers, he took action, pacing. He is said to have screened John Ford's 1939 western "Stagecoach" 40 times before making "Citizen Kane."

From Georges Méliès, the turn-of-the-century French magician turned filmmaker, he borrowed illusion. "Citizen Kane" is full of cinematic tricks: none so breathtaking as the moment when the camera seems to actually pass through a glass skylight as it swoops down into a deserted nightclub.

And going back to the origins of cinema, he borrowed one thing that had been missing from most movies ever since: sensation.

The first movie audiences had screamed in fear when the locomotive seemed to be rushing toward them. They gasped when "Little Egypt," the hoochie coochie dancer from the 1893 World's Fair, seemed to shimmy right in front of them. They were scandalized, in 1896, when the first movie actors kissed in close-up. These films caused a commotion.

Welles provided, for 1941, an almost equivalent shock. He made a "tell-all" movie about a powerful, dangerous public figure — William Randolph Hearst was the Rupert Murdoch of his day — and dared him to do something about it.

He did, of course. Which is why "Citizen Kane," despite rave reviews, opened in only a few theaters, and was mostly overlooked at the Academy Awards (it did win a best screenplay Oscar for Mankiewicz and Welles). Welles had his creative control taken away. After that spectacular debut, he struggled for the rest of his career.

"Citizen Kane" is a showoff's movie. Which is why there was a minority that didn't like it, when it opened at the RKO Palace Theater in New York on May 1 (it opened nationally the following September). And there's a minority that still don't.

"Some commentators permitted themselves to observe that Welles' much-discussed camera virtuosity consisted largely of devices more experienced directors had learned to avoid because they drew attention to the film-making process," Richard Griffith and Arthur Mayer noted in their book "The Movies."

But drawing attention to the film-making process was precisely Welles' style. Just as it was his style to draw attention to himself.

"Citizen Kane" may not be the subtlest movie. It may not be the deepest movie. But it is the greatest movie. And as critic Pauline Kael, one of the film's notable defenders, said, "it may be more fun than any other great movie."

Anyway, what's wrong with showing off? Welles, like Muhammad Ali, was a peacock. But it's not boasting if you can back it up.

Jim Beckerman is an entertainment and culture reporter for NorthJersey.com.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Oscar frontrunner 'Mank' helps prove 'Citizen Kane' is the greatest