Yukon gov't working to ensure school water meets lead guidelines published 5 years ago

The Yukon education department says it's working to ensure drinking water in schools meets national guidelines on lead levels — more than five years after those guidelines were last updated, and only after a recent Grade 8 science fair project brought the issue to light.

Why the government didn't act sooner, though, remains unclear.

The Yukon government announced this month that it had recently reviewed water testing reports from 2018 and 2019 and found that "further testing and possible remediation" was required at 30 schools to guarantee that lead levels met standards introduced in March 2019.

The review came after a science fair project by Lilou Lefebvre and Olive Passmore, students at Del Van Gorder School in Faro. The two found, among other things, that there was lead in their school's water due to the building's pipes and fixtures.

Elevated lead levels at Del Van Gorder in 2018 were also what triggered the Yukon government to do water testing and make subsequent repairs at that time.

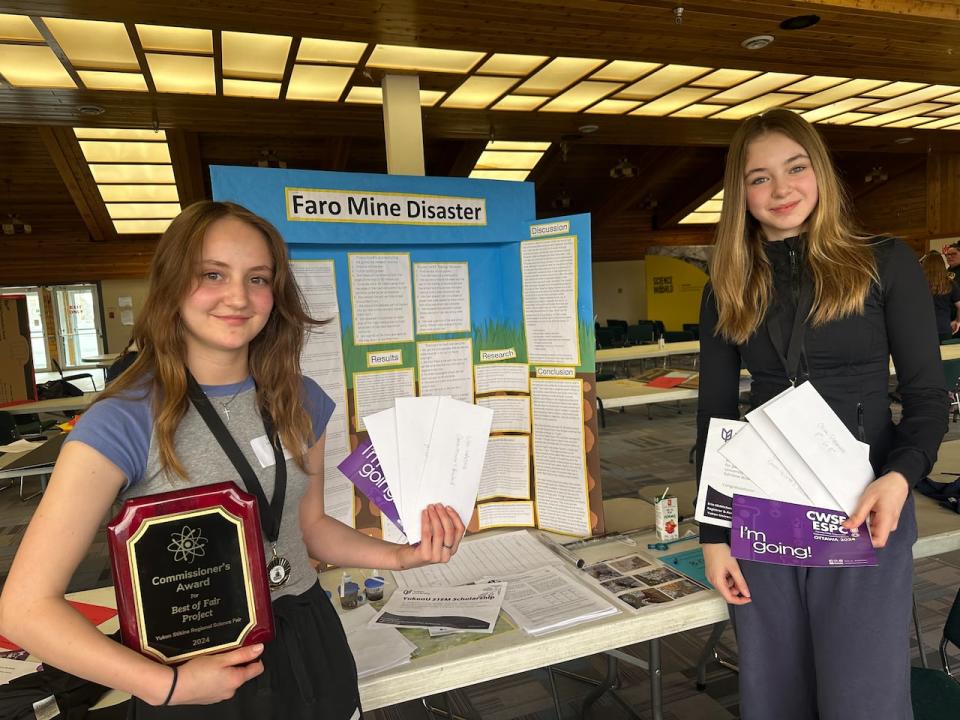

Lilou Lefebvre, left, and Olive Passmore at the Yukon-Stikine regional science fair in Whitehorse in March. The Del Van Gorder School students' award-winning project found, among other things, that there was lead in the drinking water at their school in Faro, prompting the Yukon government to test drinking water at all of the territory's schools. (Elyn Jones/CBC)

The education department's acting director of operations confirmed in an interview May 14 that the students' findings triggered the review of previous test results, and that the department would be hiring an external contractor to test the water at all Yukon schools.

"What I would reiterate is that, you know, we always look at the health and safety and well-being of our students and staff — that remains our highest priority," Jayme Curtis said.

Curtis also pointed to comments from the Yukon's chief medical officer of health (CMOH) that there are no immediate health risks associated with consuming lead concentrations "slightly above the national standards" for a short period, and that concerns arise with exposure to lead over a lifetime.

Curtis has only been in his role since April and said he could not answer questions about why the department hadn't reviewed the old test results earlier, or done a new round of testing.

CBC News asked the education department for an interview with someone who had been at the department longer, and who could speak to why the department didn't act when Health Canada updated its drinking water guidelines in 2019.

Department spokesperson Michael Edwards responded via email eight days later.

"We acknowledge that the new Health Canada guidelines were published in 2019," he wrote, "and are committed to ensuring all our facilities meet the safety standards set out by the Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality."

Department used different lead standard

The education department's commitment to meeting the standards in the Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality, however, appears to be a new development.

While the department made multiple references to the guidelines in an email to parents earlier this month and in public messaging, it was following a different standard — outlined in another Health Canada document entitled "Guidance on Controlling Corrosion in Drinking Water Distribution Systems" — until very recently.

That standard allows for a much higher maximum concentration of lead to be present in the drinking water of non-residential buildings — 0.02 mg/L.

The Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality only allowed a lead concentration of up to 0.01 mg/L, until March 2019 when Health Canada cut that to 0.005mg/L.

Edwards, the department spokesperson, confirmed that water in Yukon schools was being held to the corrosion standard, writing that it was a "joint decision made by the Department of Education and the chief medical officer of health, based on the guidance available at that time."

The school water testing reports in 2018 support this, with the equipment used only able to detect a minimum lead concentration of 0.02 mg/L. Any samples below that threshold were described as having less than 0.02 mg/L of lead, making it impossible to tell if the samples met the drinking water quality guideline at the time of 0.01 mg/L or less.

The Yukon education department, however, has publicly conflated the two different standards, stating in its email this month to parents that testing of school water fixtures took place in 2018 to "make sure they met the Canadian Drinking Water Guidelines in effect at that time."

The department also claimed in a May 1 news release that "Health Canada has revised the Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality, lowering the maximum allowable concentration (MAC) for lead from 0.020 mg/L to 0.005 mg/L." In fact, editions of the Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality dating back to 1968 have never listed 0.02 mg/L as the maximum allowable concentration for lead.

It's unclear why the department is now choosing to follow the drinking water quality guidelines instead of the corrosion guidance.

All testing and fixes, if required, are expected to be completed over the summer and before the start of the 2024-25 school year. In the meantime, Curtis, the acting director of operations, said that any school water fountains that previously tested above acceptable lead levels have been shut off and have had signs placed on them.

Del Van Gorder School, he said, has also been given bottled water for students and staff, and a handful of other schools in the territory have recommended that students bring water from home.

Del Van Gorder school in Faro has been given bottled water for students and staff, according to the education department. (Paul Tukker/CBC)

Elsewhere, staff have been instructed to "flush" fountains for five minutes in the morning. While flushing is a common way to reduce lead concentration in stagnant water, the Guidance on Controlling Corrosion in Drinking Water Distribution Systems notes that it "may not be sufficient to reduce the levels of lead and copper below the guidelines."

It quotes a paper from 1993 that "demonstrated that the median lead concentration in samples collected from drinking fountains and faucets in schools had increased significantly by lunchtime after a 10-min flush in the morning."

'There's a lot of questions out there and it's concerning'

At least one school council thinks that the department has more explaining to do.

The Selkirk Elementary School Council in Whitehorse, sent a letter on May 9 to Education Minister Jeanie McLean asking, among other things, why action wasn't taken sooner.

"There's a lot of questions out there and it's concerning," council member Melanie Davignon said in an interview.

"Those are our kids, right? And those teachers, those administrators, all of the adults working in that system in those schools, is that going to be an issue for them down the road?"

The Yukon's opposition parties also want answers.

While Yukon Party MLA Stacey Hassard praised the Faro students whose project brought the issue to the government's attention, he questioned why the education department hadn't been proactively testing for lead.

"I mean, it's interesting and maybe a little bit scary that this is what caused the department to finally take some action," he said.

Yukon NDP leader Kate White said the government had to take more accountability, especially given that elevated lead levels in school water had triggered the testing in 2018.

"I'm not sure why this dropped off or why someone wasn't paying attention, but my expectation is now that it's been brought back up to the surface again, thanks in large part to those students in Faro, that now we'll see, you know, concrete actions taken to resolve the issue," she said.

Yukon CMOH Dr. Sudit Ranade, meanwhile, reiterated in an interview that generally, short-term exposure to higher levels of lead don't raise concerns about "acute toxicity."

While he had not reviewed the test results from 2018 and 2019, he said he was in discussions with the education department about its current response and next steps.

"It's funny, I was thinking about, you know, how would I position this as an issue along the list of all of the issues that we deal with in public health" he said of the situation.

"And I would say at this point … it's not an emergency, but it's something that requires action."