You're Practically Guaranteed to Get Alzheimer's If You Have This Genetic Variant

A team of scientists seems to have discovered a previously hidden genetic cause of Alzheimer’s. In a new study Monday, the researchers found strong evidence that people carrying two copies of a genetic variation already tied to Alzheimer’s risk are practically destined to develop the neurodegenerative disorder as they get older. As much as 2% of the general population may have the same mutation, suggesting that the genetic risk of Alzheimer’s is larger than currently assumed.

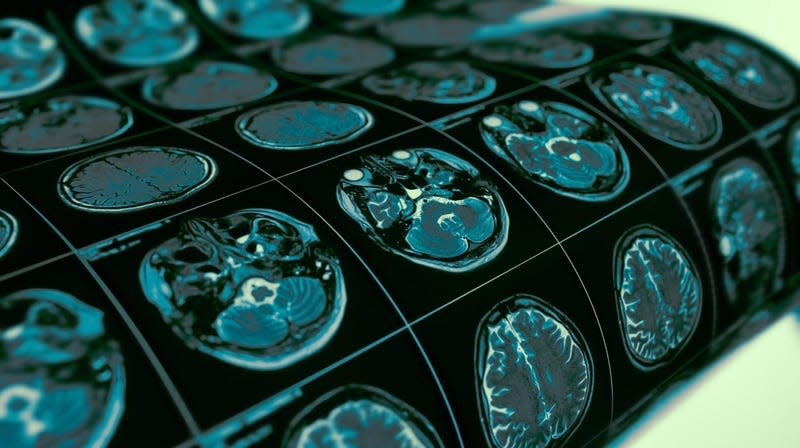

Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia, currently affecting around 7 million Americans. It’s a complex condition that can have many different risk factors behind it, including age, cardiovascular disease, and genetics. There are known rare mutations that almost always cause someone to develop Alzheimer’s at a much younger age than usual, while other mutations appear to raise the risk of the classic form of Alzheimer’s, which typically starts occurring after age 65. One of these latter mutations affects the apolipoprotein E gene, or APOE, and is known as APOE4.

About a quarter of the population carries at least one copy of APOE4, and the variant is commonly studied as an important aspect of Alzheimer’s risk by scientists. Often, these studies don’t distinguish between people having one or both copies of the gene, but some research has suggested that these dual carriers, also known as APOE4 homozygotes, have a much higher risk of Alzheimer’s than others.

A large team of researchers from Spain and the U.S. sought to settle the question. To do so, they analyzed brain donor data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) as well as data from five other large-scale studies that tracked people’s biomarkers related to Alzheimer’s, including their APOE4 status. All told, the analysis included over 13,000 people.

In the NACC data, the researchers found that nearly everyone with two APOE4 genes showed medium to high levels of brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s at the time of their death. For comparison, the same was only true for 50% of those with APOE3, the most common APOE variant, and which isn’t thought to affect Alzheimer’s risk. In the biomarker data, the team similarly found that almost everyone with two APOE4 copies had abnormal levels of amyloid beta in their spinal fluid (a potential early sign of the disease) by age 65, while 75% had positive amyloid scans. By age 80, almost 90% of these carriers had all of the biomarkers associated with amyloid and tau (another protein key to Alzheimer’s) that the researchers were able to track.

Not everyone with these changes will show clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s before they die. But the findings, published Monday in the journal Nature Medicine, provide a clear illustration of almost-complete penetrance, the authors say—the odds of a genetic mutation causing a specific trait. In this case, those with two APOE4 genes appear near certain to develop at least the early signs of Alzheimer’s by the time they reach their mid-60s. Given that level of certainty, it’s more accurate to classify this mutation as representing a distinct, “genetic form” of Alzheimer’s, the researchers argue. They also note that 2% of the population is thought to have two APOE4 copies, which would make this form of Alzheimer’s one of the most common diseases tied to a single gene.

The findings, assuming they’re validated by other researchers, could lead to important changes in how we study Alzheimer’s. For starters, it should lead to a broader definition of genetic Alzheimer’s, with the APOE4 form recognized as usually causing Alzheimer’s at an older age than other genetic causes of it. Given the much higher danger associated with two APOE4 copies, the researchers say, future studies should also not bunch them together with single copy carriers. And simply knowing about this heightened risk should hopefully help scientists better understand how Alzheimer’s can happen, which might one day lead to more effective treatments for it.

“In conclusion, our study provides compelling evidence to propose that APOE4 homozygotes [i.e. two APOE4 alleles, or copies] represent a distinct, genetically determined form of [Alzheimer’s disease], which has important implications for public health, genetic counseling of carriers and future research directions,” they wrote.