Your kidney stone: A user’s guide

I know, I know. Ew! Who’d want to read about kidney stones? That’s gross and unpleasant!

So if you’re pretty sure you’ll never have one, feel free to skip this story. But just remember: 19% of all men and 9% of all women will one day get a kidney stone. That’s 300,000 Americans every year — half a million emergency-room visits.

And in our new, hotter world, those numbers are going up. Heat leads to dehydration, which leads to kidney stones.

A kidney stone generally won’t kill you. But the pain is so intense that you might wish it would. According to some women who have both had a kidney stone and given birth, the stone hurts more than childbirth.

I never ever ever thought I’d get one of these things. And when I did, I was astonished to find out how little we know about them and how crude the treatments seem. The Web is full of conflicting information, jargony information and bad information. Even among urologists — the kind of doctor who treats kidney stones — you’ll get different advice. I should know; I’ve had three. (Urologists, that is.) (Also kidney stones.)

Furthermore, once you get a kidney stone, every step of the treatment usually comes as a rude surprise, terrifying and unknown. For most people, a kidney stone means intense pain and fear.

When my kidney stones attacked, I desperately wished I had an article like this one: a user’s guide to kidney stones.

So sit back, read and enjoy — if “enjoy” is the right word.

What it is

A kidney stone is an ugly, jagged crystal that grows inside your kidneys. It’s made of salts and crystals. It can be as small as a grain of sand, or several inches across.

A kidney stone can strike anyone. But your chances are much higher if you’re white, middle-aged or obese. The chances are even greater in hot climates, if you don’t drink much water, or if you have a family history of stones.

Oh — and if you’ve ever had one before, you’re 50% more likely to get another one within five years. What an awful piece of knowledge! It’s like a curse.

Now then: If your stone is small, you may never know you had one. You just pee it out without even noticing.

The nightmare scenario is when the stone is small enough to escape the kidney but big enough to get stuck in your ureter — the skinny, fragile tube that connects your kidney to your bladder. Usually, stones get stuck in one of three spots in the ureter: the top, the bottom, or the middle.

And since you’ll probably ask: No, there’s no way to dissolve a kidney stone. (At least not the kind that 80% of us get — the kind made of calcium oxalate. More on that in a moment.)

How to know when you’re having an attack

When a stone gets stuck — oh, dear heaven, you’ll know it. The hours of your first attack, you’ll remember until the end of your life.

The pain is beyond description. You may feel it in your side or back, below the ribs, or down by your groin. You’ll try to find a position that eases the pain, but there isn’t one. It’s a stabbing, vicious pain that takes your breath away. People liken it to dragging razor blades through your guts or twisting an ice pick around your insides.

Surprisingly, the pain doesn’t come from the stone; it comes from the blockage. The stone plugs your ureter, so pee starts backing up the tube and making your kidney swell up. That’s what hurts.

You can’t believe this is happening to you. If it’s your first attack, you also have no idea what is happening to you, and that’s part of what makes it terrifying.

Your body starts going haywire. You’ll probably start throwing up, shaking, and feeling like you constantly have to go to the bathroom.

I’m telling you this not to gross you out, but to reassure you. Believe it or not, this train wreck inside you is normal. For someone having a kidney stone attack, that is.

Just when you’ve decided you’d better get to a hospital, your stone may play a cruel trick: You suddenly seem to feel better. Abruptly, the pain eases up a lot.

What has actually happened is that a little urine has managed to push past the stone, relieving the pressure. (You go, pee!)

Unfortunately, the pain returns shortly thereafter. Kidney stone attacks can go through 20- or 30-minute pain cycles like that.

Anyway: Sooner or later, you’ll get yourself to the emergency room.

Pro tip No. 1: Start drinking water. A lot. The more you pee, the better your chances of flushing the thing out.

Pro tip No. 2: Do not drive yourself to the ER during an attack.

The ER visit

At the hospital, you may have to sit there in agony, waiting for your turn. Eventually, a nurse will record your blood pressure, weight, and other vitals.

Once you’re checked in, an ER doctor will finally visit you. If the physician thinks that a kidney stone is causing your pain, you’ll probably get a CT scan or an X-ray to confirm your stone’s size and position.

A nurse will probably start you on hardcore pain meds like morphine, plus antivomiting meds, and fluids through an IV.

Scan, pain meds, fluids. And that’s really all they can do in the ER.

Stones, like most other medical things, are measured using the metric system. Pretty soon, you’ll hear the statistic that you’ll be able to swap with other sufferers for years to come. You’ll hear, “You’ve got a 3-millimeter stone” or “a 7-millimeter stone,” or whatever.

If your stone is 4 millimeters or smaller (about one-fifth of an inch across), it’s 80% likely that you’ll just pee it out. The ER doctor will send you home with instructions to drink like a fish and pee into a strainer, so you can catch the stone for analysis. (To be clear: Drink water.)

If the stuck stone is bigger than 4 millimeters, though, they’ll tell you to make an appointment to see a urologist.

Just pray to the kidney gods that you can get in to see one promptly. Until you do, the only thing that will keep you sane is drinking lots of water and taking pain pills.

Three kinds of scans

Through your kidney stone adventure, you may be sent in for any of four kinds of scans:

X-ray. Simple and quick, but the picture isn’t especially detailed. It might miss smaller stones. X-rays subject your body to radiation, which could slightly increase your risk of cancer.

CT scan (or CAT scan — same thing). This kind of picture is much sharper and more detailed, because the scanner rotates around your body in a complete circle. (You’re lying on a table that slides into a body-size tunnel.) The drawbacks: A CT scan is very expensive; it’s not available in rural hospitals; and it too involves radiation.

Ultrasound. This is the same kind of test women get throughout their pregnancies. You lie down on a special bed, and a technician runs a handheld scanner over your abdomen. What’s great is that an ultrasound doesn’t give you any radiation at all. What’s not so great is that an ultrasound provides a pretty crummy picture. Most kidney stones don’t show up at all. All an ultrasound can see is whether your kidney is swelling up because of a blocked ureter. That’s a good way to answer the question, “Is the stone still there?”

None of these tests hurt at all; they’re just a little weird.

Blasting your stone to dust

OK then. It’s been determined that you’ve got a stuck stone, and it’s too big to “pass” (to get peed out by itself).

In that case, someone’s going to have to get it out. Modern medicine offers two ways to do it: Blast it or grab it. (The urologist may refer to these as surgeries, but neither one, in fact, involves cutting you open.)

Since I’ve had both procedures, I’d be delighted to describe them for you. I also met with an expert in the treatment of kidney stones, Dr. Joseph Del Pizzo, Director of Laparoscopic and Minimally Invasive Urology at NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medicine, to help explain them. (Dr. Del Pizzo did not treat my kidney stones.)

First, your urologist may offer you shock wave lithotripsy. (The full correct term here is extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, meaning an “outside the body” “stone-crushing” “with pressure waves.” No wonder doctors often just say “ESWL,” and patients just say “lithotripsy.”)

On the appointed day, you lie down on a special table. You’ll either be put to sleep (general anesthesia) or just sedated enough that you won’t remember anything beyond the popping sound of the cannon. (Doctors try to avoid general anesthesia if possible, because it carries risks of its own.)

Then they park a rather amazing cannon over your body. In the course of 30 minutes, it fires 2,000 highly targeted shock waves at your stone. If all goes well, the blasts smash the thing into kidney-stone crumbs. In the days and weeks to come, you’ll pee them out without a care in the world.

The shock wave machine has a built-in X-ray gun, so that the urologist can check the focus every now and then. (The stone can move around during the procedure. You would too if you were being blasted 2,000 times.)

Once you wake up, you can go home after about an hour. You’ll be really sore for a couple of days because, as my urologist explained, “it’s basically like someone punched you 2,000 times in the same spot.” You’ll be given prescription pain pills and encouraged to drink a lot of water. (Pain pills and water. Starting to sound familiar?)

You’ll also be given a strainer and instructions to pee through it. The hope is that you’ll catch what’s left of your stone, so that a lab can analyze its makeup.

So, yes: It’s very cool that doctors can blast your stone to bits without having to cut you open.

Unfortunately, shock wave lithotripsy isn’t especially effective. Your urologist may not even try it if the stone is really big or in a bad spot in the ureter.

And get this: Even when you do have the procedure, it succeeds in blowing up your stone only 60% of the time.

Yes, that’s right: You might go through all of this and wake up to find that it didn’t work.

Or that it only partly worked. It may have broken up the stone, but the pieces may still be too big to pass, so you’ll have to have another shock wave session later.

Reaching in and grabbing it

The shock wave treatment is the most common kidney-stone procedure, but there are lots of reasons you might need plan B instead. Maybe your stone’s size or placement isn’t right for shock waves. Maybe the shock waves didn’t work. Maybe you didn’t want shock waves, because you’d rather have something that’s more likely to work the first time.

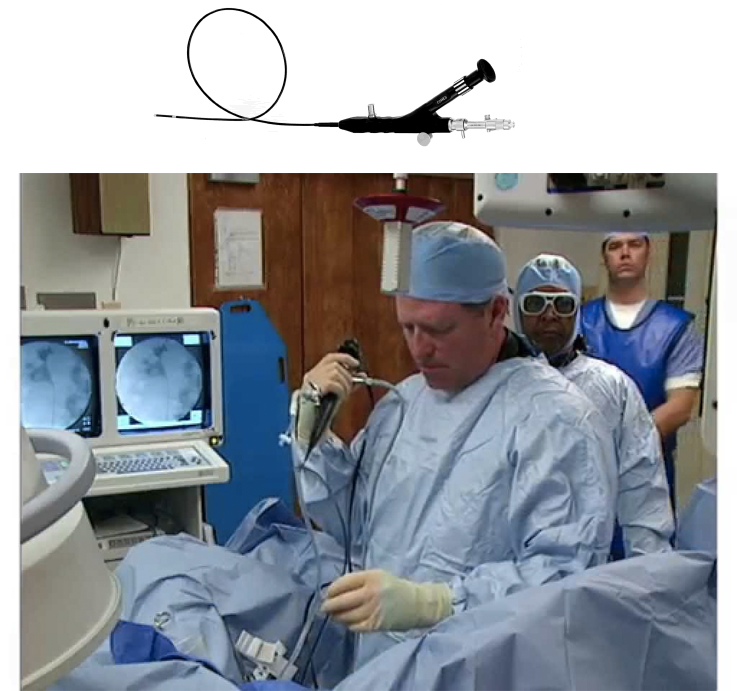

So what’s plan B? It’s called ureteroscopy. (“Ureter-OSS-ka-pee.”)

And that’s when they slide a skinny tube up into you — through your bladder, into the ureter, even all the way to your kidney, if necessary. There’s a camera on the end of the tube and a fiberoptic light; the urologist watches on a screen. The physician can even slide a laser on a wire into this tiny tube, with which to blast your stone to bits. Then the doctor can thread in a tiny grabber basket to pull out the pieces.

This scoping business has a 90% success rate. It can also handle any size stone, although it’s best for stones in the bottom half of your ureter. (If it’s up high, the urologist may use the scope to push the stone back up into the kidney, so that it can then be blasted apart with the shock wave lithotripsy. You get to enjoy both procedures for the same stone!)

So how do they get these tools into your body? Well, they — how shall I put this? They thread it in the way nature intended for pee to come out.

And yes, if you’re a guy, that’s a horrific thought. They thread a tube up your… you know.

Now, let me stress that you’re unconscious for this procedure — general anesthesia. You wake up and it’s all over. Gentlemen, your private parts aren’t even sore afterward.

The only actually horrible part is anticipating what’s going to happen to you.

Actually, some people are fine with it. “Go for it. As long as you’re going to get the damn thing out.”

Other people, not so fine. Some guys, my urologist told me, are so repulsed by the concept that they decline the procedure.

(There is, by the way, a third approach to removing your stone: actual surgery, in which the doctors make a small incision in your back, then break up and suck out the stone. You might get this operation—called percutaneous nephrolithotomy—if your stone is really big, or if there are a whole lot of stones. This surgery is fairly rare, though.)

The horror of the stent

I would love to tell you that once you’ve had your stone smashed or grabbed, your journey through the hellish underworld of pain is over.

For most people, though, there’s one more unpleasant chapter.

During your shock-wave or scoping procedure, the urologist will probably leave a little parting gift inside you: a stent.

It’s a very thin plastic tube — looks almost like a fat wire — about 10 inches long. It runs from your kidney, through your ureter, down into your bladder. Each end has a curl, which is supposed to hook the stent in place at each end.

The purpose of this stent is to prevent the ureter from swelling shut after either of these procedures. It allows urine to flow freely and lets stone particles flush on out. You’ll have to have the stent in place for anywhere from a couple of days to a few weeks.

The problem with the stent is that it’s another thing that hurts.

Especially during the first few days, you’ll have to pee a lot. (What’s happening? The curl of the stent rubs against the lining of your bladder, which sends your nerves the false message that you have to pee.) And the peeing hurts a lot. And is bloody.

By the second or third day, the discomfort of the stent may ease up. At that point, it’s merely uncomfortable for some people; it just feels like there’s a 10-inch plastic tube inside your guts.

But for some people, it’s excruciating. Worse than the kidney stone attack. Especially when you’re peeing. Which happens a lot, because (shocker) you’re supposed to keep drinking a lot of water.

That, alas, was my deal. Peeing felt like a red-hot poker in my back, a sledgehammer in my gut, and burning at the exit.

If you really want your hair to stand on end, read some of the testimonials from stent sufferers on kidneystoners.org:

“I have never felt pain like this. I can’t walk or stand because the pain is so bad. I just want all the pain to just stop.”

“Last night I wanted to pound my skull on the driveway to make myself unconscious.”

“Death sounds better than living another day with this pain.”

Of course, the people most likely to post comments online are people with bad outcomes. Here and there, you can also find comments like this one: “I was so afraid of having this procedure done after reading all of these comments. But I can honestly say that I have had minimal discomfort. Everyone has a different experience, but they are not all horrible.”

(My urologist says that maybe 20% of patients with a stent have excruciating pain; a poll on kidneystoners.org puts it at 60%.)

Anyway, here’s what I learned about stent pain.

If you’re having stent pain, ask the urologist about it! Hardcore pain meds like Percocet and Vicodin generally don’t help much with stent pain. But there are meds that relax your bladder to prevent spasms, and there’s a urine-numbing pill.

My urologist recommended slow, deep breathing during peeing. That sounded at first like new-age hogwash, but it really helped. (Much later, I asked him why. He said that it’s because all the anxiety about the pain you’re about to feel actually makes you clench up and feel worse.)

A heating pad can help.

Short-term stents (a couple of days) often come with a string hanging out of you. Believe it or not, you’re supposed to pull the stent out yourself when the time comes, by smoothly hauling on that string. It’s over in three seconds.

If your stent doesn’t have a string, you have to return to the doctor’s office to get it out. The urologist will numb you up, then go inside with that tube-scope thing (the cytoscope) and grab the bladder end of the stent. (You’re fully awake for this; usually, if you’re interested and you ask nicely, you can even watch on the screen. For me, it was a welcome distraction.)

Then there’s a three-second gentle pulling sensation, and the stent is out.

Lots of people worry about the stent coming out, but trust me: It’s a nonevent, a big fat nothing. There’s no pain. It’s quick. And after the ordeal you’ve been through, it’s a huge relief. The stent pain and the peeing pain stop almost immediately.

My stent enjoyed three weeks inside me. Once it was out, I was pain-free for the first time since the stone attack two months earlier. I’m a fairly stoic guy, but I’ll confess: After the stent came out, I walked out of the medical building, collapsed against the wall, and let tears of relief and emotion run down my face.

About the lemon water

No medicine can prevent future kidney stones (at least, not the calcium-oxalate kind that most people get).

What you can hope to do, though, is change the chemistry of your kidney. You can deprive the crystals of the ingredients they need to grow.

The urologist may order for you what looks like a big orange gasoline jug. You’re supposed to pee into it for 24 hours and then send a sample of your urine to a lab, which then analyzes how your diet may be contributing to your stones.

If you’ve got calcium-oxalate stones — the common ones — you may be advised to cut back on foods that contain oxalate, like chocolate, nuts, and dark leafy vegetables. (So much for that favorite chocolate-almond-spinach salad you love so much.)

Furthermore, the usual dietary advice for everyone in America — less salt, sugar and meat — goes double for kidney stone sufferers.

Do not cut back on calcium, though. Calcium is good. It binds with the oxalate and flushes it out of your body.

But the dietary changes are small potatoes next to the big one: Drink lemon water. A lot of it. Every single day from now on. Carry around a water bottle with you, and drink all day long. Drink so much that your pee comes out clear.

The citrate in the lemon juice is the key. It makes it hard for stone crystals to get a foothold. If you keep up with your lemon-juice drinking, you can cut your chances of getting another stone by half.

Adopting this new habit is worth it. It’s worth doing anything to avoid another stone.

Straight-up lemon water tastes pretty good, actually, but the second choice is lemonade. It’s the same lemon juice, but of course you’re getting a lot of sugar.

Third best is just drinking a lot of water. A common thread in kidney stone cases is dehydration.

(Online, people suggest Crystal Light lemonade. One urologist told me that it’s basically the same as actual lemon juice; another said it’s worthless, except as a tastier way to drink straight water.)

Kidney stones and the future

For a medical nightmare that affects so many people so traumatically, it’s fairly amazing how little we know and how little we can do about kidney stones.

That’s why people online talk about herbal remedies or about jumping up and down (or even riding roller coasters) to dislodge a stone. That’s why we’re still placing stents, the way we have been for 50 years.

We don’t know exactly why kidney stone occurrence is on the rise. We don’t know why kidney stone formation peaks in your 40s (women) or 50s (men). We don’t know why some people get them and others don’t. We don’t know if herbal remedies work, if cranberry juice works, if Crystal Light works, or if Flomax (tamsulosin) does any good. (It’s a prostate medicine that might be prescribed for you to help a stone move along.)

“There have been studies,” one urologist told me, “but it’s mostly soft data.” (That is, small studies with not-ironclad protocols.)

If you get a kidney stone — well, first of all, I’m sorry. It’s an awful, awful experience and you don’t deserve it.

Once you’ve lived through your first kidney stone, by the way, your next attack may be a lot less traumatic. For one thing, I recommend carrying around an emergency kit: a set of pills (prescription pain pills, antinausea meds, and Flomax). That way, the next time a stone attacks, you can avoid going to the ER. You already know what’s happening to you, and you have exactly the same tools that the ER would use: pain meds, antinausea meds, and fluids. (Why antinausea? So that you can keep fluids down.)

My three stone attacks (2012, 2014, 2016) have introduced me to a remarkable community: the millions of people who’ve had kidney stones. We’re part of a club nobody wants to join, but we’re also strong. We’re not squeamish when we talk about bodily processes. We’ve lived through agony and emerged with a deeper appreciation for the simple gift of being pain-free.

Many people are thrilled to find a community of fellow sufferers online, at sites like kidneystoners.org. I was among them; this site was a revelation.

There are, by the way, people whose life timelines are studded with kidney stones. Some people have had seven, or 30, or hundreds. Some people live with constant stone attacks and have mastered the art of medicating and passing them. Somehow, life goes on.

All right: That’s the end of my kidney stone user’s guide. Now go drink some water.

David Pogue is the founder of Yahoo Tech; here’s how to get his columns by email. On the Web, he’s davidpogue.com. On Twitter, he’s @pogue. On email, he’s poguester@yahoo.com. He welcomes nontoxic comments in the Comments below.