Is THIS the year Texas goes Democratic? How grassroots organizers hope to make it happen

EL PASO, Texas — Like millions of other Americans, Mary Ibarra started settling into a sports bar on Super Bowl Sunday hours before kickoff, a long day still ahead of her. But unlike most of the Brass Monkey bar’s patrons, she was not sporting Eagles green or Patriots blue, but instead a shirt that read “When they go low, we go local.”

Ibarra was at the Brass Monkey not to watch the game — as a Cowboys fan, she wasn’t enamored with either option — but to register voters for next month’s primaries. Texas’s primaries are early (March 6) and citizens have to be registered 30 days before. As a staffer for the voter outreach organization Voto Latino, Ibarra had been on the ground for three weeks organizing volunteers to expand the base of voters and encourage turnout in an area that’s highly populated (El Paso County is the eighth largest county in the state) and heavily Latino (82.2 percent, per 2016 census estimates). The Super Bowl registration effort, here and at another bar across town, was part of a final push. (Texans will still have until Oct. 9 to register to vote in the general election, and Voto Latino plans to keep up its efforts until then. But with studies showing voting as habitual, getting people to the polls for the primary is a good way to improve their chances of showing up in the general election.)

Voto Latino is one of the many groups addressing the biennial question posed by political prognosticators — “Is this the year Texas turns blue?” The Lone Star state hasn’t gone for a Democrat in a statewide race since 1994, and no Democratic presidential candidate has won here since Jimmy Carter in 1976, but there’s a belief that it’s just a matter of time. Texas is becoming more and more Latino, and because Latinos generally vote Democratic, turning blue is regarded as a foregone conclusion. There are encouraging signs for Democrats: Hillary Clinton lost the state by 9 points, the first single-digit margin for a Democratic presidential candidate since 1996. A January poll puts President Trump at 54 percent disapproval among Texans, at a sample size of over 13,000 respondents.

But hopes for a Democratic wave depend on correcting the extremely low turnout and registration among Texans, particularly among the Latino population. So there is plenty of work to be done on the ground, which is where Ibarra and other organizers across the 268,580-square-mile state come in.

(Voto Latino bills itself as nonpartisan, but it’s closely connected to a number of Democratic politicians, and polling says its target demographic of young Latinos strongly support Democratic candidates.)

“Voto Latino does national work, we register voters in all 50 states,” said Jessica Reeves, the group’s chief operating officer. “But places like Texas are incredibly hard because we focus on young Latinos who are very digitally savvy and trendsetters in terms of consuming social media … but when it comes to registering and becoming a voter in Texas, it’s incredibly hard and incredibly old school.”

The difficulty Reeves mentions is that Texas voters cannot just register online, because the state requires mailing in a form or in-person registration. The in-person option is tricky in Texas, which requires that voters be registered by a volunteer deputy registrar certified in a specific county to be legally permitted to register voters there. The process varies from county to county, but in some areas, the training or test might be offered only once a month. With 254 counties, it makes coordinating a statewide drive nearly impossible, leaving it to local organizations to do the work county by county.

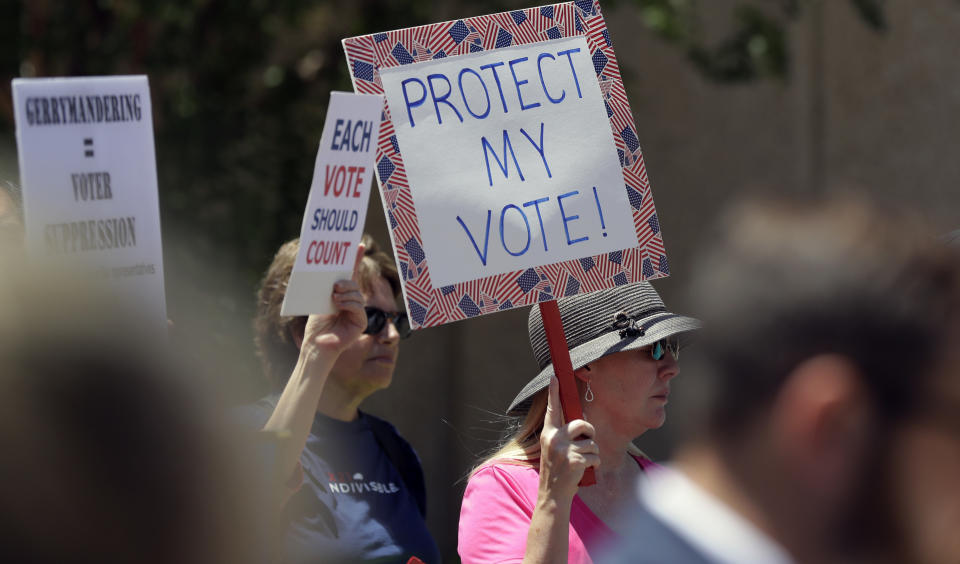

Compared to other states that offer same-day or even automatic voter registration, Texas’s process is exceptionally difficult to navigate. When combined with strict voter I.D. laws that hinder turnout of the voters who are registered, it creates a major challenge for organizers.

“Door-knocking, shopping malls, farmers’ markets,” said Ibarra, ticking off different tactics her team had used to seek out unregistered voters. “It’s hit or miss what will work and what won’t, so you try to cover as much as you can.”

“This is a citizen’s problem,” said Drew Galloway, executive director of MOVE San Antonio, a voter mobilization group that pushes for progressive policy. “You have to go out there and get that done.”

Galloway credits his organization’s work as one of the reasons San Antonio elected last spring a left-leaning mayor and a City Council that is perhaps the most progressive in the city’s history. Per MOVE, under-35 turnout was up 300 percent from the 2015 to 2017 municipal election, and the group has registered thousands more over the last three years.

In addition to the restrictive voting laws, the sheer size of Texas can make it difficult to use grassroots tactics generally deployed in areas with higher population densities. For that, the Texas Democratic Party has turned to a sort of digital door-knocking to reach voters of all ages.

“Traditional canvassing in these rural areas is pretty difficult turf,” said Tariq Thowfeek, communications director for the Texas Democratic Party. “So we’re trying to target them with social media and digital because everyone’s grandma and grandpa is on Facebook now.”

Thowfeek added there was a concerted effort to push voting by mail, which is available to senior citizens and people with disabilities.

There is a gubernatorial race and four congressional districts that could flip from red to blue, but the main target for Democrats is Ted Cruz, the state’s junior senator. Cruz has a slightly negative approval rating among Texans and a reputation of alienating people, from his college roommate and Senate colleagues to Inigo Montoya and Luke Skywalker. Cruz has definite advantages — name recognition following his 2016 presidential run, millions in cash on hand and the potential backing of the billionaire Mercer family — and early polling in the race gives him an 8-point lead with a large swath of undecideds. Although that’s a comfortable lead, that’s half his final 2012 margin.

The primary reason for the enthusiasm is the challenger who has the race within single digits: Rep. Beto O’Rourke, a former El Paso councilman and one of the city’s favorite sons. O’Rourke is putting the work in to get his name and message out — he’s over 80 percent of the way to hosting a town hall in every county since his campaign launch in March 2017, per numbers provided by his staff — but polling still paints him as an unknown to much of the electorate. On the fundraising front, O’Rourke outraised Cruz to close out last year despite declining corporate contributions, but the incumbent still has an overall financial advantage.

But if O’Rourke or the Democrats’ 2020 presidential nominee is going to have a chance in the state, it will be due to the work of people like Ibarra, a Rio Grande City, Texas, native who serves as Voto Latino’s organizing and operations coordinator. On Monday, the final day voters could register to vote in the primary, she started her morning signing up students at a local high school, an arena that has recently served as a contested venue in the state’s electorate skirmishes. There has been an effort to encourage principals and superintendents to comply with a laxly enforced 1983 law requiring schools to circulate voter registration materials to eligible students at least twice a year. But last month, the Republican state attorney general issued a nonbinding opinion stating that schools shouldn’t bus students to the polls. Considering a majority of younger voters voted Democrat in 2016, expanded registration in this area could be a boon for the Democrats.

As the deadline neared, the focus moved to colleges, with volunteers fanning out across community college campuses while Ibarra set up shop at the University of Texas at El Paso. The response of students passing through the university’s library was predictable: some eagerly signing up, some making promises to return after they rushed to their latest class and others simply ignoring the queries of “Are you registered to vote?” During a break in the action, one of the volunteers, Raquel Mejia, said she had registered members of her own family at a recent reunion, wasting no opportunity to expand the rolls.

Iliana Holguin, who is the chair of the El Paso County Democratic Party, is also doing her best to bolster her party’s chances. All 191 of her precinct leaders are volunteer deputy registrars, and they encourage door-knockers and activists to receive the training as well. She also has plans to expand the campaign to the more rural counties to the east. And it’s not just in West Texas: A member of O’Rourke’s campaign staff said that the staff regularly has town hall attendees across the state stand up and let the rest of the crowd know they’re volunteer deputy registrars if anyone needs to get registered.

One major obstacle for Democrats in their attempt at a Longhorn breakthrough is the reelection campaign of Gov. Greg Abbott. Abbott enjoys one of the highest net favorability marks of any U.S. governor and has raised over $43 million for the defense of not just his own seat — the status of the Democratic primary is too murky to predict his specific challenger at this point — but the rest of the contested races across the state. Abbott did well with the Latino vote during his 2014 run and has been looking to expand on that margin, but Democrats say his administration’s policy banning sanctuary cities could hurt his chances with Latinos.

“We plan to wage, if necessary, hand-to-hand combat with our opponents to win the Hispanic vote,” said Dave Carney, Abbott’s campaign adviser, in an October 2017 interview with the Texas Tribune.

Abbott’s policies have hurt registration and turnout in the state, endorsing tighter voter ID laws and targeting one group that registered low-income Texans. As attorney general, Abbott targeted an organization called Houston Votes, ordering an armed raid of its offices in 2010 under allegations of voter fraud. Charges were never filed, but the organization’s records and equipment were destroyed on his orders in 2013 and the group eventually folded. Abbott had called voter fraud in the state an epidemic that was “happening on a large scale.”

As his reelection campaign rolls along, Abbott’s team is well aware of the potential wave looming, despite their myriad advantages in the state. Carney issued a memo following Democratic success in the November elections warning that Texas isn’t immune to a similar result.

“The enthusiasm gap that we face is real,” Carney wrote to Abbott aides in a memo that was obtained by the Houston Chronicle. “It is going to take a concerted effort by the campaign to overcome it, not just for ourselves, but for the down ballot races that will be depending on us to pull them over the line.”

The final day of primary registration ended with Ibarra at El Paso’s county election office, where she and her team submitted the nearly hundred forms they had acquired on the final day. She gave the staffers there plenty of notice after she arrived in town — “You always want to be on good terms with the election officials, wherever you’re at,” Ibarra advised — and things went smoothly, every new registrant submitted before the 5 p.m. deadline.

“It’s definitely something that can be replicated, especially with our model of working with college kids and campuses,” said Ibarra when asked if the effort in El Paso was possible elsewhere. “There’s plenty of other cities in the state that have a wealth of community colleges and universities — Houston, Dallas, Austin, San Antonio, the Rio Grande Valley — but a longer period on the ground would be helpful.”

The focus on El Paso and other urban areas may seem misplaced, since those are already Democratic strongholds, but there is plenty of room for growth. Clinton won 69.1 percent in El Paso County, one of her best marks in the state, but turnout was just under 50 percent, with thousands more potential voters unregistered. (Voto Latino estimates there could be as many as 130,000 unregistered but eligible Latinos just in El Paso Country.) In the 2014 midterm, things were far worse, with only 20 percent turnout.

If Democrats, and O’Rourke specifically, want to have a chance, they’ll have to limit losses in heavily conservative areas (potentially aided by O’Rourke’s barnstorming), flip some disaffected Republican voters (Trump’s low popularity could help here) and run up the totals in favorable areas (due to the efforts of Voto Latino and similar groups). Do that, and the blue revolution pundits have been positing for years might finally come to pass. If not? Prepare for the fresh wave of “Can Democrats win in Texas?” articles coming your way in 2020.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Yahoo News’ Michael Isikoff describes crucial meeting cited in Nunes memo

The neo-Nazi has no clothes: In search of Matt Heimbach’s bogus ‘white ethnostate’

In wake of church shootings, pastors and worshipers arm themselves to shoot back

Photos: Syrian government airstrikes kill dozens in rebel-held Eastern Ghouta region