Former WWII refugees send letters of hope to Syrians

This article originally appeared on The Daily Saint.

Gunter Nitsch lived on the brink of starvation after he and his mother and brother were captured from their home in East Prussia by the Russian Army in 1945 and forced to live in labor camps for three and a half years.

Despite the war raging in Europe, Nitsch and his family had lived relatively unscathed in the countryside. When the Soviet army moved on the offensive through East Prussia in early 1945, Nazi officials gave strict orders to the civilian population not to flee. When his family finally and desperately tried to make their way to safety in the west, it was too late.

Nitsch was seven. His mother worked 12-hour days in the fields in exchange for 300 grams of bread each day. There were no toilets, no showers, no toothbrushes and certainly no toys. At night his mother would go into the field and steal potatoes for her family. Nitsch’s biggest fear as a child was that his mother would be caught and sent to Siberia.

He was 11 when they crossed illegally into a West German refugee camp, a former ammunition dump. The war was finally over. But his family had no clothes or papers. They were infested with lice and bed bugs. “It was the first time I held soap and took a shower in three and a half years. I just washed and washed and washed. I was afraid the dirt around my knees was embedded in my skin,” Nitsch said.

The refugee camp was better — there were toilets and he and his family were no longer starving — but still they couldn’t afford anything more than bread, potatoes and vegetables. His clothes were shabby, and they barely had enough food, never mind toys to play with. Nitsch became enamored with paper planes, entertaining himself for hours by folding up scraps of paper and watching them soar through the air. Schoolmates called Nitsch and the other refugee kids “Pimocken,” (Polish for Potato Beetle) and “Rucksack Deutsche” (“Backpack German”). “It referred to the fact that we came with nothing but maybe a backpack on our back,” explained Nitsch.

When asked how he kept hope when life felt so hard and uncertain, Nitsch recalled a phrase his mother repeated when he was young: Weeds like us don’t perish.

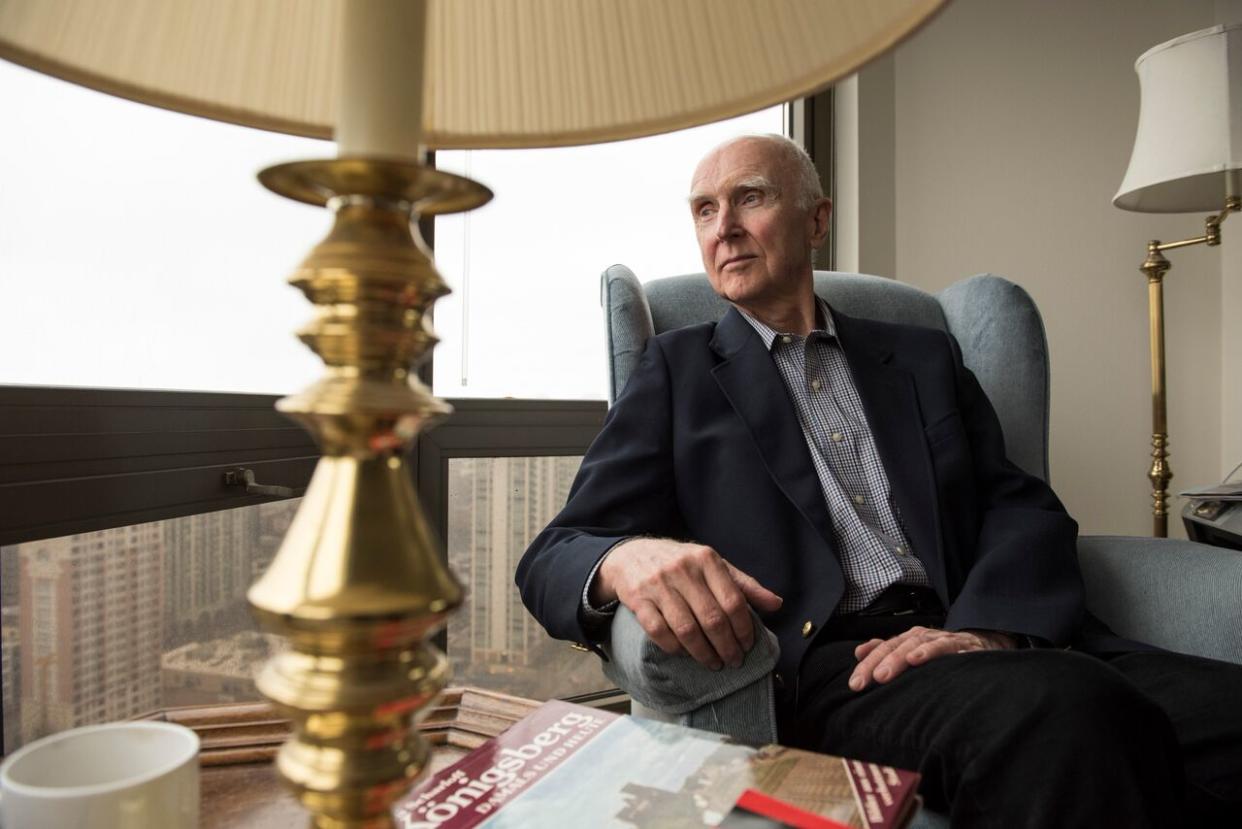

“One day out of the blue” in the early 1950s, a package from people in Belville, Penn., came for Nitsch and his family. It had been sent through the new organization CARE (then the Cooperative for American Remittances to Europe), which was created to send parcels for people struggling and starving in the aftermath of World War II. “I had never seen anything like what I saw in front of me,” Nitsch, now 78, said. The box was filled with rice, ham, prunes, fruit salad, “all in fancy packaging,” cocoa powder, coffee, and a one-pound chocolate bar. “When I took a bite of the fruit salad, I’d never tasted anything like it. I thought, ‘This must be what angels eat in heaven.’”

Over the course of two years at the camp, Nitsch and his family received more than a dozen packages from that same family — the Peachys. His mother would write back, and though neither family could read the language, they continued to correspond. After Nitsch moved to the United States in 1964, he and his American wife, Mary, whom he met in New York, tracked down the family in Pennsylvania. Nitsch considers the Peachys among his best and most life-long friends.

“They saved my life. They gave us hope.”

School and reading books were other areas where Nitsch said he found hope. “War changes people, and the best thing someone can do is keep getting an education.” He couldn’t read enough of the dime novels he’d find about the Wild West. “I wanted to go to America and be a cowboy.”

Instead he got a job at a supermarket when he arrived in New York at the age of 26 and eventually went on to receive his B.A. from Hunter College and his master’s degree from Pace University. The Chicago resident has continued to take classes in “literature and art and music and history” throughout his life.

More than one million CARE packages were sent from the U.S. during the post-World War II era, and the organization recently reached out to some of those original CARE recipients to see whether they wanted to write letters to those who are currently living as refugees. Nitsch jumped at the chance to extend the same lifeline to others that he once received.

Nitsch wrote to 8-year-old Zaher, a Syrian boy living in Jordan, the same age as Nitsch when he lived the life of a refugee.

“I am 78 years old and live in the United States,” Nitsch wrote from his Chicago home in a letter to Zaher. “Seventy years ago, when I was 8 years old like you, I was also a refugee. I‘m writing to share my story with you to let you know that, no matter how bad things may seem, there are good people in this world who can make everything better.” (Read and listen to Nitsch’s full letter to Zaher here)

A week after Nitsch put the parcel in the mail, Zaher sat with his father and siblings in Jordan and opened it. An aid worker helped to translate the letter from English to Arabic. “He reminds me of my grandfather,” Zaher said as he looked at the current photo that Nitsch included in the package. Zaher then pulled out the paper airplane Nitsch had folded for him. “Zaher’s Airline” was written on the piece of paper. Zaher threw it, and he and his sibling giggled as it soared through the air.

According to the UN, there are currently more than 4.8 million externally displaced refugees by the Syrian Civil War, and more than 1.2 million are living in Jordan.

“Living through this war has affected Zaher’s psychological state so much,” Zaher’s father told CARE. “Things are not available the way we need them to be, and I cannot provide for him like I did when we were in Syria.

“My hands are tied here. I have nothing to give now.”

In regard to Nitsch’s letter, Zaher’s father said: “I felt like it was me who was also suffering right with him. It was like reading my life.”

Nitsch isn’t the only World War II refugee who has sent letters to displaced Syrians. After receiving a letter from World War II refugee Helga Kissell, who now lives in Colorado, 16-year-old Syrian refugee Sajeda said: “[She] made me feel like I exist.”

Syrians “have been struck by how similar the stories of the World War II refugees are to their own, in terms of those feelings of isolation and a longing for home,” said Brian Feagans, director of communications at CARE. “They also have drawn hope from learning that people in dire circumstances much like their own have gone on to live happy, full lives.”

“But I think the most overpowering emotions are appreciation and comfort knowing there are people out there who care for them,” said Feagans.

The Syrian refugees’ living conditions are undeniably harsh, said Nitsch, so he was “relieved” to hear Zaher is among the children who are able to still go to school while living in the camp. He wonders what will happen to Zaher, in the same way he wondered as a boy what his future would hold. “Will he get a good education, a good job? Will he get married?”

The day after receiving the letter from Nitsch, Zaher and his siblings woke up. The 8-year-old boy got dressed, ate breakfast, and filled his backpack with the new markers, pencils, and crayons he’d received from Nitsch. He left his temporary home and walked to school with his siblings.

Weeds like us don’t perish.

The Daily Saint is a blog focused on people doing good things for one another. Find more stories from The Daily Saint on its Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter pages.