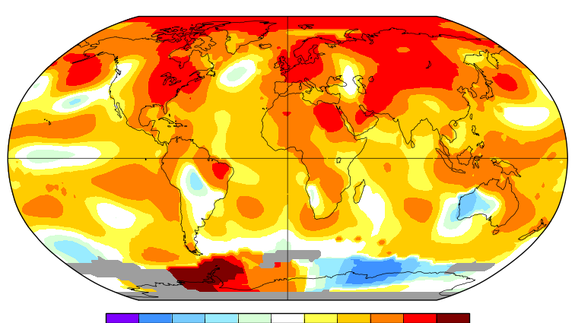

World headed for up to 3.4 degrees of warming despite Paris treaty

Although historic international progress has been made in the fight to slow global warming during the past two years, it may not be enough.

The world is still headed for a temperature rise that is well above the target the international community is aiming for.

This is the sobering conclusion of a new U.N. report released on Thursday morning, which found that warming of between 2.9 to 3.4 degrees Celsius, or 5.2 to 6.1 degrees Fahrenheit, is likely by the end of the century if countries meet their pledges under the Paris Climate Agreement but don't commit to cutting another quarter off predicted 2030 greenhouse gas emissions.

SEE ALSO: The disturbing climate implications of this sailboat's Arctic voyage

The target set under the Paris Agreement, which goes into effect on Friday, is a maximum warming of 2 degrees Celsius, or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, above preindustrial levels by 2100.

Anything more than that, scientists and political leaders say, would carry too high a risk of irreversible impacts on global ice sheets, resulting in the drowning of small island states. The likelihood of other dangerous outcomes such as longer droughts, more intense and lasting heat waves would also increase.

The assessment comes a few days before U.N. officials begin the next round of climate talks in Marrakesh, Morocco.

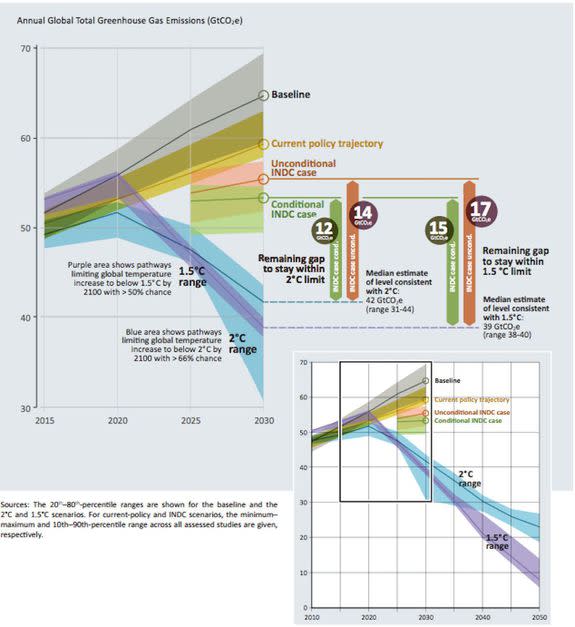

Image: UNEP Emissions gap report 2016

A key topic at the climate summit will be whether countries, particularly the biggest polluters like China and the U.S., will step up and offer more stringent emissions cuts on near-term timetables. So far, most emissions cuts under the Paris Agreement are pegged to 2030.

The U.S., for example, is expected to present a plan in Marrakech to largely decarbonize its economy by 2050, though it may not formally commit to taking that step in part due to uncertainty surrounding next week's election.

The UN report, known as the "Emissions Gap Report," is an important report card for the world's government and business leaders who are seeking to curtail the speed and severity of global warming.

Although it does not give the world a letter grade, a close reading of the document reveals such an evaluation would likely be a C, or the minimum passing grade, at best.

Image: Zhou jianping - Imaginechina

The report found that under current emissions reduction commitments, the world will have burned nearly all of the carbon that can be combusted while still remaining under Paris' 2-degree Celsius target. This would leave little room for rapidly developing countries like India to grow their economies while wrestling with rising emissions.

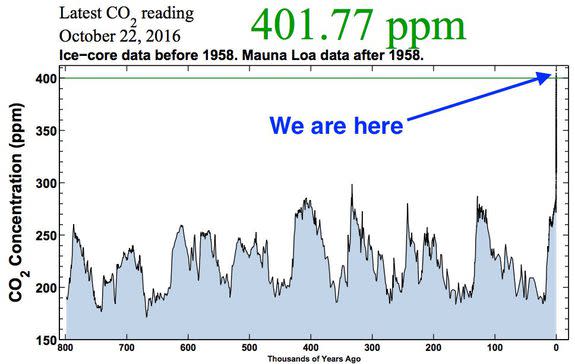

To put that another way, this means that the so-called "carbon budget," which is the amount of carbon dioxide-equivalent pollutants that can be released into the atmosphere without exceeding a particular temperature target, will be "close to depleted" by 2030 even under a scenario in which all of the world's Paris pledges are met, the report found.

After 2030, then, the world's carbon account will be overdrawn, and incurring increasingly painful penalties.

Image: Scripps institution of oceanography

"This year's Emissions Gap Report brings a greater awareness of the challenge ahead of us," the United Nations Environment Programme's (UNEP) chief scientist Jacqueline McGlade told Mashable via email.

Even including the Paris Agreement as well as other recent steps, McGlade says that countries will still need to cut an additional 12 to 14 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents per year in order to reach the 2-degree target by 2100.

"Given that 1 gigatonne is the equivalent of taking all cars [off] European roads for one year, it is clear that we have much to do. And the earlier we act the better," she said.

Interestingly, the UNEP report notes that most scenarios limiting warming to 2 degrees Celsius or less by 2100 foresee a reliance on as-yet unproven technologies that would yield actually remove carbon from the atmosphere.

Some climate scientists have dismissed such an assumption as overly optimistic at best.

"If we don’t start taking additional action now, beginning with the upcoming climate meeting in Marrakesh, we will grieve over the avoidable human tragedy," said U.N. Environment director Erik Solheim in a press release.

"The growing numbers of climate refugees hit by hunger, poverty, illness and conflict will be a constant reminder of our failure to deliver. The science shows that we need to move much faster.”