World Bank president to teen robot-builders: Build technology that helps people

A horde of rolling robots overran a concert hall in Washington, D.C., on Monday and Tuesday.

The machines built by 163 teams of teenagers to compete in the inaugural First Global Challenge had one job: collecting and sorting plastic balls in a small arena approximating a stream passing through a village. But they also had a higher purpose: reminding everybody watching to make technology that helps people.

“Automation, technology, artificial intelligence will eliminate half to two thirds of the jobs in developing countries,” World Bank president Kim Yong Kim said in closing remarks. “Be focused on ensuring that technology actually creates new jobs.”

Kim pointed to the use of drones in Rwanda to deliver donated blood to anywhere in the African nation in less than hour, while in Kenya 98% of money transfers now happen via mobile phones. Similar ingenuity, he suggested, can make drinkable water a reality everywhere.

Said Kim: “You can be the generation that solves the most difficult problems in the world.”

The competition held at DAR Constitution Hall benefited from bonus publicity beyond what it could have earned from being founded by Segway inventor Dean Kamen. The U.S. State Department refused to issue visas to an all-girl team from Afghanistan, then upheld the decision even after reversing an earlier denial to Gambia’s team. Those rulings and their subsequent override (as the White House first told Politico) by President Donald Trump only raised the event’s profile.

Geopolitical drama, however, was nowhere in sight Tuesday afternoon and evening. What I did see: a lot of motivated gearheads working side by side—often from traditionally opposed countries—to get their mechanical contraptions to work as advertised before the clock ran out.

One set of parts, many outcomes

The idea behind the First Global concept was to raise awareness about bringing drinkable water to the 663 million people who lack it. So each team’s robot had to collect blue balls (symbolizing clean water) and orange balls (contaminants). They deposited the blue ones into a “water reserve” and dropped the orange ones into a “laboratory.” To finish, robots had to avoid a coming flood by driving atop a bridge at one end of the 4-meter by 5.5-meter arena or hoisting themselves on the railing around it.

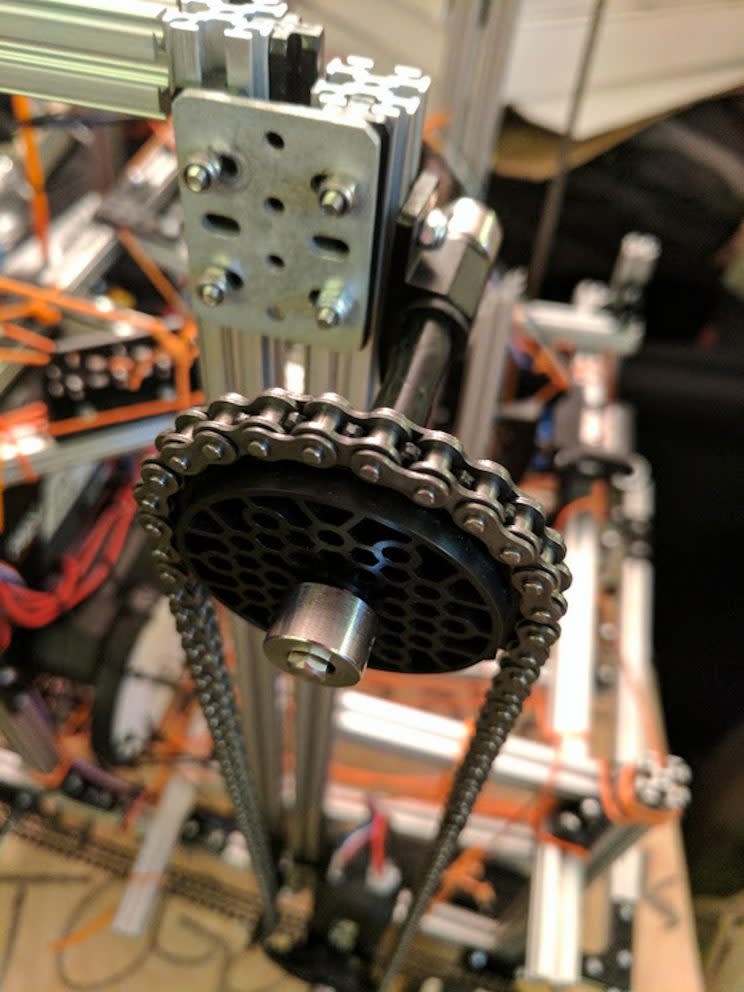

To keep things fair, every team got the same box of components. The resulting machines all had wheels on the bottom and didn’t exceed 50 centimeters on a side when placed on the field. But they often had little else in common.

“There’s so many different ways to approach the same problem,” said Team USA member Sanjna Ravichandar of Plainsboro, New Jersey. The robot she and her Everett, Washington-based teammates Katie and Colleen Johnson built—nicknamed “Rosie” after World War II’s Rosie the Riveter—featured six wheels for greater stability. It swept balls up from the floor and past an optical sensor that sorted them by color and dumped them into one of two storage compartments.

Katie Johnson said the design—developed over one and a half months through “a ton of Hangouts, Google Docs and texting”—needed multiple revisions before the robot could hoist itself properly.

Team Israel’s robot was on display across a hallway from Team Palestine’s and only a few feet from Team Iran’s. It required its own frequent iterations, as documented in a glossy volume. “All the mechanisms were changed at least two or three times,” said Rinat Hadad, a student from Beersheba.

Team Afghanistan had the same parts as everybody else but much less time, owing to shipping delays. “Other teams had four months, we had two weeks,” said mentor Alireza Mehraban.

Robots can be fussy

In each match, three teams on each side using video-game controllers had 2.5 minutes to collect and sort balls, then either park or hoist their robots, as color commentators excitedly talked up the details.

That sometimes proved impossible. Team Ethiopia’s robot shed a chain and stopped. Team Mali’s had a battery come loose. Robots from Kyrgyzstan and Georgia fell over, while Team Russia’s couldn’t hoist itself at the end of a match. Machines from Kuwait and a continent-wide team representing Asia got their wheels stuck together.

Audience members waved flags and cheered, but not always for their own countries. As the robot from the Syrian-refugee contingent Team Hope scooted around during a round late in the afternoon, Team Lebanon’s members—easily identified by their giant rainbow wigs—led a “Team Hope! Team Hope!” chant in the stands.

Team members’ t-shirts and flags grew increasingly cluttered with the signatures of other teams’ members as the afternoon went on and empty pizza boxes accumulated in the hallways around the auditorium that the Daughters of the American Revolution opened in 1929.

At the end of a closing ceremony featuring nine other awards in such categories as “Engineering Design” (India) and “Courageous Achievement” (South Sudan), top honors in the contest went to Team Europe, followed by a silver for Poland and a bronze for Armenia.

A serious purpose

The challenge laid out by Kim and Kamen–who in his own closing remarks told contestants “you’ve got to develop your skills and technology to end extreme poverty”—would be a tall order for any demographic.

But after seeing what groups of teenagers from around the world could build in their spare time, I feel a little more optimistic about their ability to fulfill it.

More from Rob:

How a system meant to keep your money safe could put it in danger

A ruling against Google in Canada could affect free speech around the world

Email Rob at rob@robpegoraro.com; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.