With Trump CIA directive, the cyber offense pendulum swings too far

A recently revealed change in covert action authority may presage an escalation in the ongoing cyberwars and the distinct possibilities of excessively provocative U.S. action, retaliation on U.S. soil and attacks on financial institutions.

The policy pendulums in Washington are often at one extreme end of their swing, only to move to the other extreme a few years later. On most policy issues, being on the extreme end of the pendulum swing generates dysfunctional governmental action. Such risks are especially true when the policy governs cyberwar or covert action or both together.

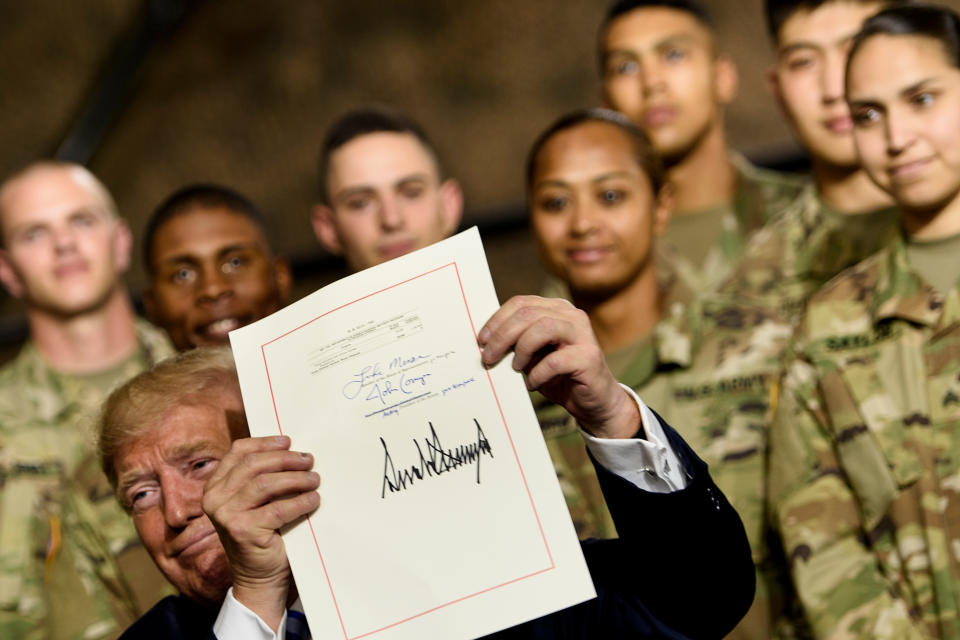

Yahoo News recently reported that in 2018 President Trump signed an intelligence finding, the requisite step under the laws governing U.S. intelligence activity to initiate covert action. Such covert actions are not about intelligence collection, but rather they concern changing things in the real world, sometimes by causing objects to be blown up. It appears that a 2018 finding on offensive cyber activity may be one of those times, according to Yahoo News, permitting CIA’s cyber teams to more easily cause explosions and other damage to critical infrastructure abroad.

After the exposure of the U.S. cyberattack on the Iranian nuclear program, President Barack Obama reportedly believed he had been misled about how effective and how secret that CIA operation would be. He then imposed new rules, requiring extensive, interagency policy and legal review of any new, offensive cyber operation. The Obama administration was heavily populated with attorneys and did sometimes engage in overly extensive legal review of national security issues, often allowing lawyers to intrude in the policy process with opinions not based on the law. The result was that the pendulum swung to one extreme, inaction.

The U.S. military was not allowed to hack into potential enemies’ systems so that, in time of war, they could disable them. That created a problem because it takes weeks or months to hack into some targets, and if the military had to wait until a war began, it would be too late. Congress fixed that problem in 2018 with the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act, and the administration followed with National Security Decision Memorandum 13, permitting “cyber preparation of the battlefield.” U.S. Cyber Command was off to the races. The military, however, is constrained by the laws of war and requires that attacks minimize collateral damage. Moreover, for most of what Cyber Command was authorized to do, there would be no damage, disruption or destruction unless there was a shooting war.

The CIA, it now appears, received new offensive cyber authorization at the same time. Usually covert action findings address a policy issue such as nuclear proliferation or terrorism. Instead, the new finding reportedly addressed a capability, which involves hacking both to collect information that would then be publicly revealed and to destroy physical objects in the real world. No longer would the CIA have to go through any interagency review before attacking. Decisions would be made with only CIA personnel involved. The State Department would not be at the table to offer considerations on timing or diplomatic initiatives. The Department of Homeland Security would not be present to express concerns about retaliation or the revelation of a cyber exploit that could then be employed against U.S. companies. The Treasury Department would not be there to insist on the sanctity of financial institutions.

About to invade Iraq and cause the deaths of thousands of U.S. military personnel in the process, George W. Bush was still unwilling to allow hacking of an Iraqi bank to move money out of the country. He did not want to create a precedent. The international banking system depends upon a level of trust that the numbers in financial institutions’ accounts are accurate and have not been manipulated by nation-state attacks. Bush, therefore, maintained the red line against covert action against banks. This administration has apparently crossed that Rubicon and authorized CIA cyberattacks resulting in the public release of credit card information.

The revelation of the CIA’s cyber covert action authorities comes within days of a series of explosions in Tehran, Iran, some at infrastructure facilities and some at nuclear and missile plants. Suspicion was focused on Israel for some of those explosions. Now we must consider whether the U.S. partnered with Israel or acted unilaterally as part of its “maximum pressure” campaign against the Tehran regime.

Iran has retaliated for past cyberattacks, including creating a massive outage at major U.S. banks, destroying systems at a Las Vegas casino owned by Sheldon Adelson, wiping all software at Saudi Aramco’s corporate network and attempting disruption of an Israeli water system. We can expect further retaliation as the U.S. tightens the vice on Tehran.

There are many dedicated professionals at the CIA and its cyber division, and much of what they do is necessary. However, the CIA has a history of excesses, for example taking its authorities a step too far with prisoner interrogations and drone attacks. Letting the CIA engage in unsupervised cyberattacks is likely to be a recipe for disaster. The pendulum needs to swing back toward a middle ground.

Richard A. Clarke was the national coordinator for security and counterterrorism in the White House from 1998 to 2001. He is chairman of the board of governors of the Middle East Institute, and CEO of Good Harbor Security Risk Management, which advises companies and governments on cyber security.