Wisconsin mom decided ending pregnancy was safest, most humane option. Then she had to leave state.

TAYLOR − Before leaving their home Nov. 9 for the Mayo Clinic across the state border in Rochester, Megan and Sam Kling sat down with their oldest daughter to tell her why they would be spending a night out of town.

"The baby is sick and is going to heaven," Megan remembers telling her 4-year-old, Greta. She and her husband knew their youngest, Elma, 20 months old at the time, was too young to understand. "We wanted Greta to know and remember the baby was real."

The path to that conversation began 10 days earlier when a routine, 20-week ultrasound − conducted when Megan was 21 weeks and 5 days into her pregnancy − at the Krohn Clinic in Black River Falls found a low amount of amniotic fluid surrounding the fetus.

At the appointment, her physician, Dr. Kaitlyn Cunningham, could not confirm the diagnosis but said she had "a pretty good idea" what was going on. The fetus likely had a condition that is impossible to survive.

"I try to be as careful with my language as possible," Cunningham told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. "I do not want to offer false hope, and I want my patients to be able to make informed decisions."

(The Journal Sentinel received permission from Megan to discuss her medical history with Cunningham, who has worked at the Krohn clinic for three years in family medicine and surgical obstetrics.)

Cunningham's medical assessment was confirmed four days later by a second, more specialized, ultrasound for high-risk pregnancies performed at Gundersen Lutheran Medical Center in La Crosse. The fetus had bilateral renal agenesis, a condition incompatible with life because the two kidneys never develop. The kidneys are responsible for clearing waste out of the body and controlling fluid balance.

The condition occurs in approximately 1 in every 3,000 to 4,000 births, with overwhelming predominance in males, according to the National Institute of Health. It has a 100% mortality rate and there is a 33% chance that the baby will die in utero, Cunningham said. The cause of the condition is unknown.

"My initial reaction was "I don't want to be pregnant anymore,'" Megan said. "It was like going into survival mode. I did not want to deal with whatever was going to happen next."

In a typical pregnancy, vital organs begin to develop around eight weeks. If the kidneys, which process urine, do not properly develop, the amount of amniotic fluid surrounding the fetus will be low, since urine is a component of the fluid.

Although Megan never missed a prenatal appointment, it is impossible to diagnose the condition prior to the 20-week ultrasound. The organs are too small to see if they are developing properly, Cunningham said.

Cunningham said even with more frequent, weekly ultrasound monitoring and the mother delivering early, the outcome is the same, a deceased baby.

"I knew the baby was not going to survive," Megan said. "To carry my baby that I knew was going to die for another four months sounded to me like pure torture."

But that was and remains the only option for women in her situation in Wisconsin.

Doctors stopped performing abortions in Wisconsin for more than a year following the overturning of Roe v. Wade in June 2022 by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Planned Parenthood’s Milwaukee and Madison clinics had resumed abortion services for those up to 20 weeks pregnant in September, following a Dane County Circuit Court judge’s preliminary ruling in July that signaled an 1849 law banning feticide did not apply to consensual abortions.

But Megan’s pregnancy was too far along.

On Nov. 3, the date of the Gundersen appointment, Megan was 22 weeks and 2 days pregnant. She remembers the doctor, who happened to be a traveling doctor on hire from California, looking at the nurse and asking about Wisconsin's abortion law.

Megan wanted to stay in Wisconsin. She wanted to be induced and have her baby in Black River Falls. She wanted Cunningham to be with her through the process. That was not an option.

"We talked after that appointment," Cunningham said. "She was venting frustration at the law, at the system. Having little control over such a life-changing event was understandably hard for her."

Cunningham continued to support and advise Megan and Sam on their options.

They decided to keep an appointment Cunningham had advised her to make with the Mayo Clinic, in case the baby's condition was confirmed as incompatible with life. Megan had less than two weeks to have the procedure in Minnesota, where abortions are legal up to 24 weeks.

Sam remembers Megan calling him after initial ultrasound in Black River Falls.

"She kept saying there was something wrong with the baby," Sam said. "There is not enough amniotic fluid."

As soon as the wheels of her truck came to a stop on the gravel driveway, Sam was at her door. Greta had been with her at the appointment.

Once Greta was with her dad, Megan broke down.

Megan worried about causing pain

Megan, originally from Holmen, a town of about 11,000 people north of La Crosse, met Sam shortly after graduating from college and accepting a job near Tomah. She now works as an agronomy sales lead. Sam grew up on a dairy farm about a country block from the couple's current home in Taylor, a community of about 500 north of Black River Falls in Jackson County.

Sam is the seventh generation of Kling men in the welding-fabrication business and owns a shop on the property. It is not uncommon for a horse-drawn buggy to be seen on their property, with many in the nearby Amish community dropping off equipment for Sam to fix, Megan said.

The couple has been married for seven years. They would like their family of four to expand to five. Megan describes their daughters — Greta and Elma, who turned 2 on March 3 — as social butterflies. Photos of the family hang on the walls of the living room, a mini-slide and other toys stacked in the room's corner.

"Ever since I was a little girl, I looked forward to being a mom," Megan said. "I feel good people have to have children. That way, we have good people coming into the world."

They had been thinking through options together, then discussing those options with Dr. Cunningham since the first ultrasound.

Factoring into their decision was the quality of life the baby growing inside her would be experiencing if she carried it to term. Movement is difficult with low amniotic fluid. Low amniotic fluid also means there is no cushion for protection. Babies carried to term are often born with skeletal defects. The pressure from the mother's body forces the fetus' bones to bend as they grow.

When she leaned over to pick up or put Elma in her crib, she found herself wondering if she was hurting the baby.

"I envisioned him somewhat on life support inside of me," Megan said. "I didn't want that for my baby."

Her own mental health also was a factor. She imagined walking through the grocery store, wondering how she would respond to strangers asking her how far along she was, when her baby was due or if she knew whether she was having a boy or a girl.

"How would anyone handle that? Would you give an answer or would you tell them the truth — my baby is already dead or is going to die?" she asked.

The couple was surprised to learn that intentionally inducing a pregnancy is an abortion. Scheduled inductions are typically performed at 39 weeks or later, when the baby is viable.

"We didn't try to think of it as an abortion or a termination of the pregnancy," Megan said. "We are going to hand our baby over to God a few months early. My dad is there, Sam's grandfather is there. That's how we thought about it."

The closest option for Megan to be induced was at Rochester Mayo Clinic. Her other options for terminating the pregnancy in Minnesota included going to a Planned Parenthood clinic in the Twin Cities or Gundersen Winona Campus.

She quickly ruled out the two other options once she learned she would be sedated and the fetus removed from her uterus.

“I am still this baby’s mom,” Megan said of her thought process at the time. “We created this baby, and I’m going to be the one that brings it into this world. I felt that was the least I could do.”

She acknowledged the decision they made — to willingly deliver a baby that would be dead or die soon after birth — is not one everybody would make. But everyone should have the right to decide for themselves, she said.

"No matter which way you decide, the end result is the same. You are losing a baby," she said.

Nolan snuggled his mom skin-to-skin

Megan and Sam arrived at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, the afternoon of Nov. 9.

The process at Mayo began with confirming the diagnosis they had received at Gundersen by performing another ultrasound. Megan said they wanted to be sure there was no chance their baby would survive.

“The diagnosis was correct,” Megan said. “There was no question about it.”

Health care workers began inducing Megan around 8 p.m. She was given mifepristone to soften her cervix, then misoprostol to soften and dilate her cervix, and Pitocin to begin contractions. She had to sign for the abortion pills, the only time the word abortion was brought up during her stay at Mayo.

She was given medication during the night “so she could rest,” but a full night's sleep proved elusive. She was given IV pain medication to lessen the labor pains but as labor progressed throughout the night, "the less and less sleep" she got heading into the morning hours.

"Every time I felt a kick, I would wonder if it was the last," she said.

The Mayo staff prepared Sam and Megan for the fact their baby could be stillborn. In the event the child was born with a beating heart, staff informed them they would provide comfort care until the baby passed.

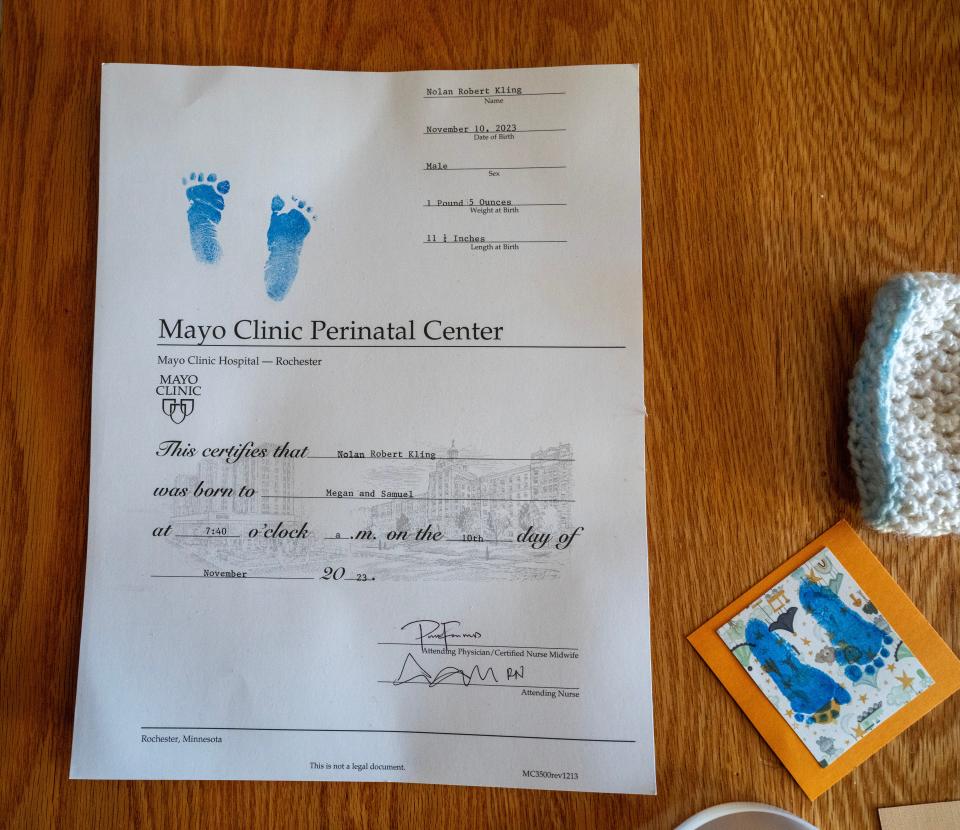

At 7:30 a.m., following nearly 12 hours of labor, she pushed once, and the baby was born. It was a boy. Megan and Sam named their son Nolan Robert Kling; Robert in honor of her dad and Sam's grandfather.

Nolan's heart was still beating.

The nurses cleaned him up, put a diaper on him and a cap on his head, then handed him to Megan to snuggle skin-to-skin to her chest, covered with a warming blanket.

"I was scared, wondering what he would look like," Megan said. "He was a little peanut. He had one club foot. It wasn't severe but it was there. He had soft baby skin and the same button nose as our daughters."

Sam and Megan took turns holding and comforting Nolan. Every five minutes or so, Nolan would kick and gasp for air. Megan had cut a piece of her dad's favorite flannel shirt and brought it to the hospital with her for support. When she held Nolan, she held the piece of flannel next to him.

"In the long run, it was a gift," Megan said. "But it was also pretty traumatic to hold him as he was trying to breathe."

It was a situation with no possibility for a positive outcome, Sam said.

"I can't say enough about the staff in Rochester," he said. "They were supportive of our choice. All we wanted was to end the pregnancy in how we believed was the most humane way possible."

Driving back home on Nov. 10, the day of Nolan's birth and death, the parents passed a billboard that read, "Abortion is not health care," with an image of a young women slouched on a bathroom floor.

"I never felt those billboards were great but I feel like the law, religion to a point, and those billboards bring an unnecessary amount of shame on women like myself. I feel it's being kicked when you are already knocked down."

That feeling is a reason she is sharing her story.

"The fact I have two daughters is the reason I am speaking out and sharing my experience," she said. "I want the world to be better for them. I don't want them to feel the unnecessary shame that I had to feel."

Sharing the message: 'People need to show more grace'

It has been four months since Nolan's death. His sister, Elma, just turned 2 years old, and Nolan's due date passed on March 6. An autopsy confirmed his condition occurred naturally, not because of a genetic defect, as can be the case with renal agenesis.

"I believe every woman has a story and every woman needs to have health care options with their doctors. It is a private matter," Megan said. "Everyone has their own story. I am a living example of that. I never thought the abortion law would affect me personally because Sam and I could never make that choice."

After going through the experience, the term pro-life carries a new meaning for her.

"I can't help but feel I am pro-life but in the sense I am pro-the mother's life," Megan said. "If we take care of the mothers, the mothers will take care of the babies and their families. Every woman should have the right to do what is best for her family."

She recalls seeing Kate Cox on news reports in mid-December when the 31-year-old Texas woman learned her third pregnancy was not compatible with life and challenged the Texas' abortion law in an effort to end her pregnancy. Cox was just a year younger than Megan, and also had two children.

Cox's case drew national attention and forced the abortion issue before the Texas Supreme Court. Like Megan, Cox ended up traveling out of her home state to terminate her non-viable pregnancy.

"I 100 percent can identify with her," Megan said. "To hear the arguments she had to listen to in court was appalling. People need to show more grace for one another."

Lawmakers in Wisconsin and the country as a whole continue to debate at what point in a pregnancy people should have the ability to terminate a pregnancy. Megan said her experience highlights the "gray area" that few people talk about, know about or acknowledge.

She has written and sent her story to a half dozen state lawmakers, including the two who represent her in the Wisconsin Legislature. Megan received a call from the office of one Democratic lawmaker she reached out to, asking if her story could be shared. Others did not acknowledge receiving her email.

"I feel dismissed," she said. "And these are supposed to be my people."

Cunningham said it is fairly common for people to end their pregnancies by being induced and giving birth, like Megan did.

"Megan made a decision to have a life-saving termination of her pregnancy. Her pregnancy was not viable," Cunningham said. "Every time a woman gets pregnant, they are risking their lives. That might sound dramatic, but you never know who will develop pre-eclampsia or some other life-threatening condition. For a mother to continue with a pregnancy that is not viable is only a risk to her."

The risk of death associated with childbirth is approximately 14 times higher than that with abortion, according to a 2012 study published in Obstetrics & Genecology.

Her short-term plans include focusing on her career, completing their family with a third child in 2025 and keeping Nolan's memory alive.

Her favorite mementos of Nolan are two books they received at Mayo, "God Gave us Heaven" and "God Gave us Angels.". The inside cover of each book includes his footprints. She reads the books to her daughters often.

"This helps them understand Nolan was a real baby," Megan said. "Even though they never got to see him and never got to meet him, he was real."

Jessica Van Egeren is the enterprise health reporter with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. She can be reached at jvanegeren@gannett.com or 608-320-3535.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Pregnant Wisconsin mom went to Minnesota for an abortion. Why?