Why the World of Typewriter Collectors Splits Down the Middle When These Machines Come Up for Sale

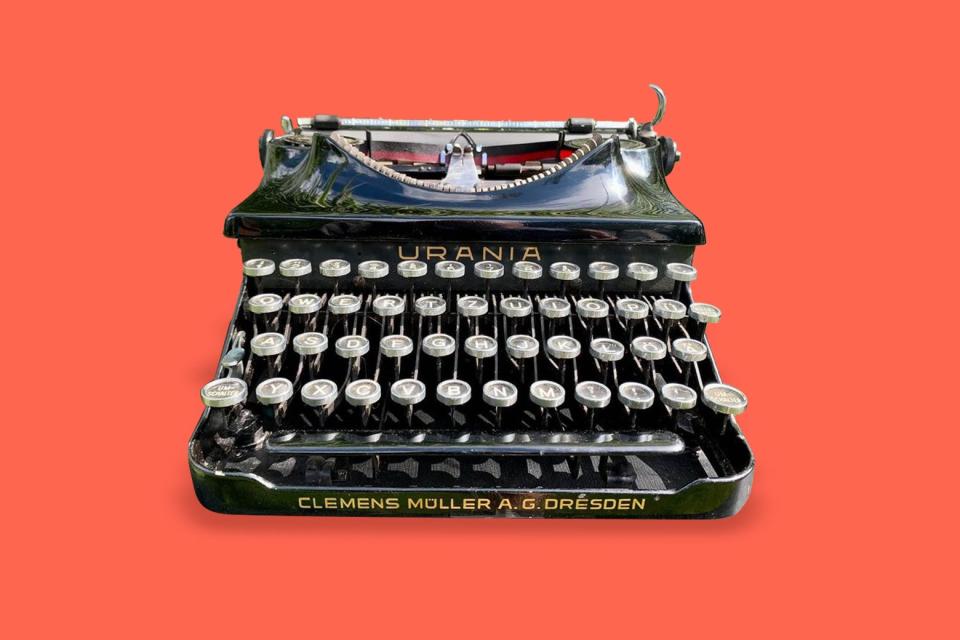

“It’s a Urania Klein,” my friend said, as he lifted the shapely antique typewriter from his car trunk. “German-made portable. Nazi-era. Built in 1939.”

It was a stunning machine—he certainly knew how to close a trade with a fellow typewriter collector.

To the uninitiated, it looks quite like any of the countless outmoded typewriters that are gathering dust in antique malls across the country. Their brand names became the vernacular of the 20th-century American office: Royal. Underwood. Remington. Smith-Corona. But this wasn’t one of those. It had a history far more tumultuous than anything Mad Men could devise, and its existence shows how those troubling historical legacies resonate into the present day.

You don’t have to be a connoisseur of antique office machinery to identify the Urania as a Nazi-era typewriter; it has that particular aesthetic. The shine from chrome-ringed, glass-topped keys accents its stern profile. From the keyboard, the high-gloss curves accelerate smoothly upward toward the basket of typebars. The position of every knob, lever, and button has been well thought-out and positioned most logically, and engineered to maximize utility.

It has the contours of a Darth Vader helmet, and shines just as black.

This machine just looks Nazi, and unapologetically so.

But how are we to appreciate these machines of both menace and beauty? Are they simply inanimate tools for writing, and nothing more? Or are they relics of the most odious regime in human history—cursed forever to be symbols of the Third Reich where they were birthed? And if such objects were born with some kind of original sin, is there any hope for redeeming them?

Strange thoughts? Perhaps. But as both an academic and collector, these are the questions that confront me every time I come across such mechanical artifacts from Nazi Germany. Encounters like this are actually a surprisingly frequent occurrence.

“It was a war trophy,” my friend interjected, though that went without saying. “It was lugged home in some GI’s duffel bag, without its case.”

As strange as it sounds today, German klein (“small” or portable) typewriters were among the most sought-after souvenirs for soldiers fighting in World War II. Think of it: Adjusted for inflation, top-of-the-line portable typewriters cost roughly the same as your MacBook Pro today, and their usable lives were measured not in months or years, but decades and generations. Consequently, thousands of Uranias, Gromas, Erikas, Rheinmetalls, Continentals, Olympias, and other high-quality, precision-made German machines were looted from Nazi military and government offices, businesses, and even from civilian homes, whether their owners were dead or alive. “War trophy” is of course a pleasant euphemism: It denotes a reward for heroism, bravery, and sacrifice, while simultaneously acknowledging that even the good guys steal, pillage, and destroy amid the haze of total war.

In most cases, the new lives of these machines were decidedly more tranquil than those they left back in Europe. This particular Urania, for example, was built in Dresden, and was sold at a shop on Ferdinandstraße in central Hamburg in 1939. But after spending its first six years in whatever unknown capacity in Nazi Germany—and a few months in a duffel bag—it then passed the next 75 years typing out invoices and receipts at a mom-and-pop general store and service station outside of Bel Air, Maryland.

Far fewer Nazis in Bel Air.

It doesn’t take an animist—going around attributing a soul or life force to inanimate objects—to anthropomorphize this Urania into some elderly German American immigrant who never acclimated to using dollars instead of deutschemarks, never lost his accented Ös und Äs, and occasionally still confounded his Ys and Zs on the German QWERTZ keyboard.

But one needn’t delve into fantasy to grasp a typewriter’s history—one need only listen and chronicle the oral histories of their owners, who are often more than happy to share.

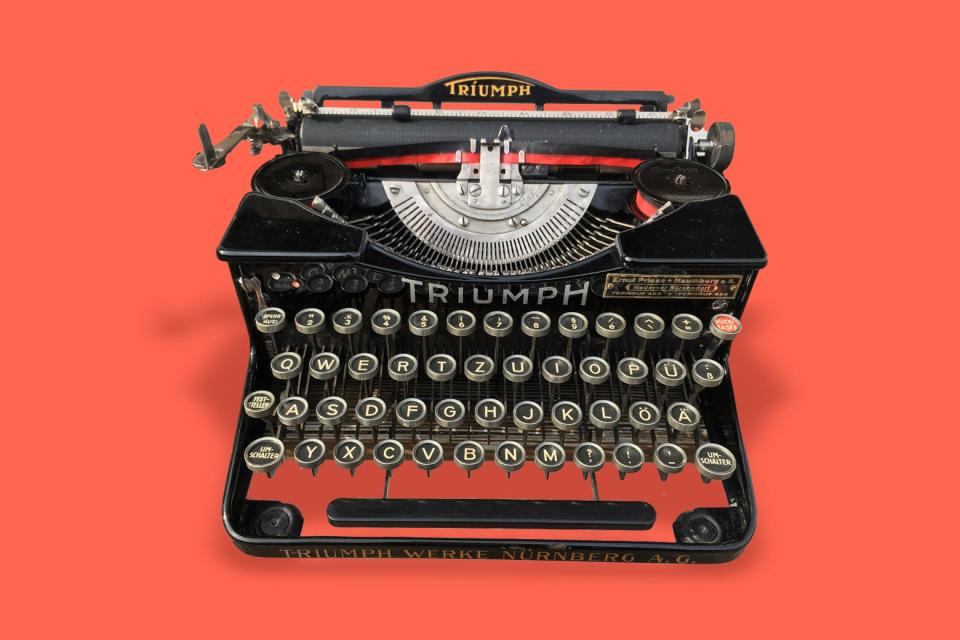

In March of 2020—as the entire country was shutting down ahead of the rapidly spreading coronavirus—my last major errand was to track down a 1929 Tríumph portable typewriter spotted on Facebook Marketplace. A young woman was selling it for her elderly Oma, so I made arrangements to visit the family’s well-kept townhouse in suburban Philadelphia.

A simple pickup that should have taken five minutes instead stretched into a two-hour interview over tea and biscuits at the dining room table as the spry grandmother with a barely perceptible accent shared with me the story of the typewriter.

She was a Sudeten German, as it turned out: part of the sizable minority of Bohemian Germans in the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia, which Adolf Hitler annexed to Germany in 1939. Keen to avoid war, at the 1938 Munich Conference, France and Britain (in-)famously hoped sacrificing the Sudetenland would satiate Hitler’s territorial ambitions.

It was a fatal mistake, and “appeasement” would become the byword for naïve Western dithering in the face of a totalitarian menace.

In the Sudetenland, the future typewriter-seller fell in love with a young Wilhelm Müller—a pacifist, poet, and aspiring musician. The typewriter was his. She smiled while recounting to me how her “Willie” would write her sonnets and love poems on it. Just glancing at the machine filled her heart with warm memories.

In the waning months of the European war in 1944—as the Nazi death machine was desperate for warm bodies to ship off to the Eastern Front—they conscripted young Willie, then only 15 years of age. Once at the front, he was wounded: Both of his legs crushed. He returned home on crutches. Most men weren’t so lucky.

At the conclusion of the war, local Czech authorities, armed militias, and regular military units ethnically cleansed nearly 3 million Bohemian Germans from Czechoslovakia. From the high-altitude perspective of postwar geopolitics, President Edvard Beneš dubbed it Czechoslovakia’s “final solution of the German question.” The view from ground level was different: Armed with AK-47s and an official ordinance, the local Czech militia knocked on their doors, informing the young couple’s families that they had 18 hours to leave their homes—and the country—forever.

As she poured me more tea, the seller matter-of-factly recounted how they explicitly instructed her to put clean sheets and linens on the beds for their home’s new inhabitants and stipulated that they could only take 50 kilograms (110 pounds) of their belongings with them. Willie’s 15-pound typewriter was one of the few things she grabbed as they were expelled to Germany.

After a brief stint in Soviet-occupied eastern Germany, they joined more than a million ethnic German refugees in the American sector of occupation. They were among the lucky ones, as some 30,000 Bohemian Germans died in the expulsions. The couple soon married and settled in Nuremberg, where the criminal trials of the remaining Nazi leadership were ongoing. Willie became a music teacher and armchair composer before passing away in the 1950s.

She later remarried the captain of an oceangoing ship and immigrated to the United States in 1961. She brought with her the typewriter as one of the few mementos of her first husband; her first love.

From the murmur of the usual family rhythms emanating from the kitchen and living room while she spoke, it seemed she’d nurtured a warm and happy family, full of loving and prosperous children, and then grandchildren. But none of them, apparently, had any interest in keeping the Tríumph typewriter. She was thankful to leave it in my charge.

“I don’t mean this to come off as strange,” she hesitated as we said our goodbyes and she showed me to the door, “but you really are the spitting image of my dear Wilhelm. I was actually shocked to see you in person, the likeness is so striking.”

That final utterance shook me, and stays with me to this day.

Still, as I drove off with the Tríumph Klein seat-belted securely beside me, I was grateful to have been privy to their fascinating story, which would have been entirely lost were it not for a collector’s quirky interest in typewriters and their history.

Unfortunately, few encounters over Nazi-era machines end so amicably.

The “Special Key”

Over the past two decades, antique typewriters have experienced a renaissance mirroring the resurgence of vinyl records. Larry McMurtry thanked his trusty Hermes 3000 typewriter while accepting his Golden Globe for Brokeback Mountain. 2016 saw the release of the acclaimed documentary California Typewriter, starring famous typewriter enthusiasts including Tom Hanks, John Mayer, and David McCullough. Ever more writers, artists, and thinkers are cutting the digital umbilical cord to their laptops and cellphones, and the persistent demands of social media and 24-hour news cycles that lay beyond. Typewriters are at the forefront of an analog counterrevolution against the nagging persistence of connectivity and information technology, in favor of privacy, thoughtfulness, and creativity.

It is ironic, then, how social media has both supercharged and democratized the hobby, whose denizens have gone from a small handful of (predominantly older, white, male, American) collectors to a truly global “typosphere” of individuals of every race, religion, gender orientation, and political persuasion, whose uniting feature is an obsession with these antiquated writing machines. The largest online typewriter community currently boasts some 29,000 members, with no signs of slowing down. As online forums go, it is a remarkably congenial and respectful bunch, with a penchant for proper spelling and punctuation.

Predictably, however, the one topic that invariably polarizes the online community is Nazi typewriters … especially those sporting the “special key.”

By the late 1930s, the iconography of Hitler’s Third Reich had even made its way onto typewriter keyboards. In very rare circumstances, a German typewriter would be made with a dedicated swastika key, like this one at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

More frequent were machines built with the double-lightning-bolt SS Siegrune, usually above the No. 3 or 5 key. With sieg meaning “victory,” the runes became ubiquitous in Nazi Germany as a shorthand rallying cry for “victory, victory!” In their more sinister application, the SS runes became the logo for the Schutzstaffel—the notorious paramilitary units most responsible for the wanton slaughter of 6 million Jews across Europe.

It is a symbol imbued with powerful resonance even today. Since modern German denazification laws prohibit the displaying of SS runes, and French laws prohibit the sale of such Nazi memorabilia—including by online auctions to sellers in other countries—savvy collectors have avoided the scorn and suspicion of mentioning the runes by name, instead simply suggesting that a given typewriter has a “special key.” Perhaps because the typical group of typewriter buyers overlaps with the far larger community of militariana collectors, typewriters with the “special key” usually command a premium, making them far more expensive than run-of-the-mill German machines, like Willy’s Tríumph or that Urania from Bel Air.

Some collectors ante up to buy “special key” machines. Others have vowed that if they come across one, they’ll grind down the metal SS-key slug to complete their denazification conversion, as many such war trophies had done to them in the immediate postwar years.

Even in this traditionally even-keeled online community, discussions of machines with the “special key” invariably go sideways, and always in the same way. Upon spotting the runes, a commenter will usually reply: “How dare you! That machine may have sent my grandparents to the gas chamber!!” (or similar), and the conversation only spirals downward from there. If you’ve ever had a political discussion online, you can probably imagine the vitriol and name-calling that follow.

To be sure, it is difficult to deny both the veracity and emotional power of this anti-fascist perspective. But the collectors of special-keyed machines also have a point.

Rightly, they argue that only in truly exceptional circumstances can one meaningfully link any individual typewriter to its particular usage within the Reich. Also, just because a machine has an SS key doesn’t mean it was used by the Schutzstaffel units involved in the Holocaust. Moreover—just like when Second Amendment defenders say to blame the shooter, not the gun—some argue that the typewriter is just an inanimate object; a tool crafted for a specific purpose, which assumes neither the responsibility of the user nor his blame. Likewise, they conclude, a typewriter with the “special key” is no more or less odious than one without; it is just a matter of the meanings we humans impart upon it.

The argument is not totally without merit. Certainly, a typewriter is not a living object, so how is it to be responsible for how and by whom it was used?

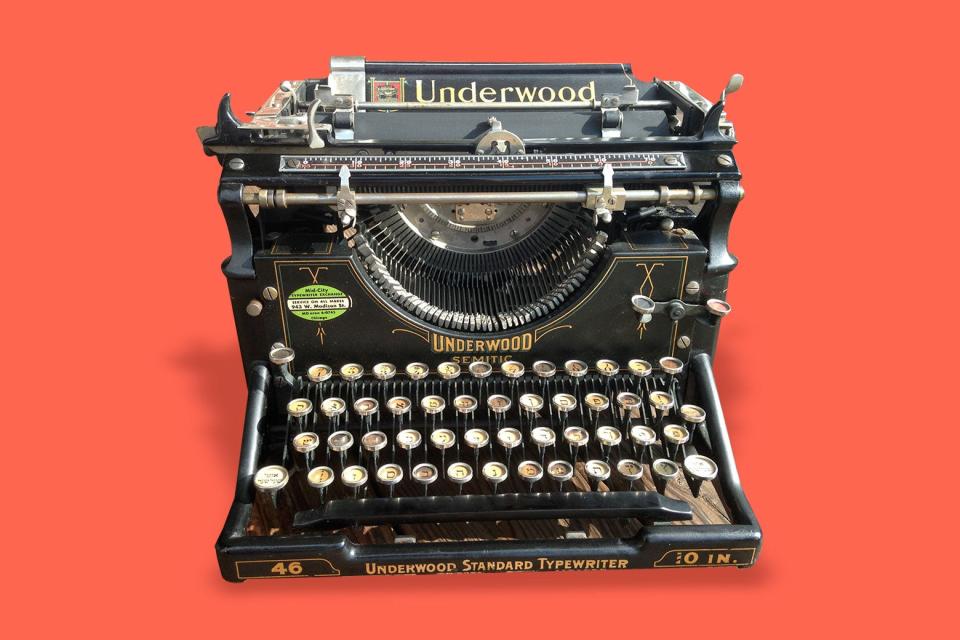

But this argument is also unsatisfactory in its downplaying of the polarizing resonance these machines have within the community. Yes, swastikas and SS runes are “just” symbols. But all the other letters on a keyboard are likewise symbols. These symbols are only imbued with meaning by the individuals who encounter them, in the broader social environment in which they’re embedded. For illustration: One of the most amazing typewriters in my collection is a rare 1923 Underwood “Semitic” 46, which types right-to-left in Hebrew script with Yiddish diacritic marks—or at least that is what I have been told. Even as I lovingly restored it, and admire it as a magnificent work of industrial art, I still cannot decipher the meaning of any symbol on the keyboard.

Yet if all symbols are created equal, and only differentiated by the meanings societies inscribe upon them, then why are some individuals drawn to the Siegrune symbol, which repulses so many—drawn to it to the point that they’d be willing to pay an additional premium for it? Even if the collector values the machine for what it does, rather than what it represents, he (and let’s be frank … it is, still, almost always a “he”) still operates within the larger society that understands and largely scorns the inhumanity the runes represent.

What these interactions with Nazi-memorabilia collectors have highlighted is that we are ultimately interested in fundamentally different things: They collect artifacts, I collect histories.

Archeologically, artifacts are simple objects, created by humans in a particular place and time—nothing more. Museums around the world are populated by historical artifacts whose meanings are murky to us, because the human context has long since been lost. Typewriters with the “special key” are unarguably artifacts of the Third Reich, just as a Royal or Smith-Corona from the same era is an artifact of our American past.

Histories, on the other hand, are chronicles of past events, which are imbued with shared meaning by human beings. Artifacts are simple objects; histories are the interpretations and values we overlay upon those objects, whether by the people who originally designed, built, or used them, or by historians who seek to understand those systems of meaning. For me, the histories of Willie Müller or that Urania from Bel Air are more interesting than a special-keyed typewriter displayed behind glass, with no human context.

As time marches ever onward, Nazi typewriters such as these will endure as artifacts, but it is their histories that are being erased as the humans who imbued them with meaning gradually pass into oblivion.

Typewriter Penance

So if an inanimate object indeed carries such symbolic baggage—even if not due to any innate fault of its own, but by the meanings society imbues it with—is there anything that can be done to cleanse a machine of those social meanings? Can a “penitent” Nazi-era machine be somehow rehabilitated? And how could that even be done by an inanimate object with no free will of its own?

The answer, I believe, is yes. If you’ve followed me this far, and agree that an inanimate tool can be denigrated and scorned by society, it logically follows that it can be redeemed by society, too. Perhaps another illustration will suffice.

In the summer of 2019, yet another German typewriter emerged for sale locally that piqued my interest. Rather than a klein, a portable machine built for mobility, this was a hulking “standard” typewriter—35 pounds of iron and steel meant to be bolted to an office desk and stay there forever. While portable German typewriters were easy enough to stash in a soldier’s duffel bag for the boat trip home, very few desktop machines made the journey across the Atlantic. This one was a 1936 Continental Standard: top-of-the-line; pound for pound one of the best writing machines ever made … and there were a lot of pounds. When the seller said it had “quite a backstory,” I was eager to find out for myself.

The typewriter was made in Siegmar-Schönau—a suburb of Chemnitz—by Wanderer, an early German pioneer in manufacturing bicycles, motorcycles, cars, and later military trucks and tanks for the Wehrmacht, the armed forces in the Nazi era. In the 1930s, Wanderer’s automotive division was one of four car companies consolidated into the Auto Union AG, which later became Audi. Indeed, one of the four interconnected rings on the Audi brand logo represents Wanderer. The typewriter division of Wanderer Werke continued unencumbered, manufacturing precision typing machines such as this one, emblazoned with its striking “WW” crest (which bears a striking similarity to the Wonder Woman logo from the 1980s). The dealer plaque affixed to the front testified that it was sold by the Baum & Herzog company in Nuremberg, while the serial number dates its production to 1936: just after the passing of the infamous anti-Jewish Nuremberg race laws. The seller filled in what happened next.

In Nuremberg, the machine was installed at Wehrkreis XIII headquarters—the German military district for northern Bavaria. The organization was charged with building and supplying the entire XIII army corps, which had spearheaded the occupation of France in 1940, and invaded the Soviet Union as part of Operation Barbarossa the following year. It makes sense that such an expensive piece of equipment would be outfitted to serve the Nazi war effort, even if it didn’t have the “special” lightning-bolt SS runes.

In April 1945, with Hitler’s forces collapsing, American armed forces conducted a pitched, five-day battle for Nuremberg en route to liberating Nazi concentration camps across Bavaria. As part of the U.S. occupying forces in the city, the seller’s grandfather had procured the hefty Continental typewriter for his own while sweeping through what remained of Wehrkreis headquarters. For a time, he kept his prize at Ferris Barracks in Erlangen, the former German military base just north of the city that housed American occupation forces after the war.

When the victorious Allies decided to move the planned trial of Nazi war criminals from the capital of Berlin to Nuremberg—itself a symbolic location, associated with Hitler’s infamous Nazi rallies and race laws—they ran into severe logistical problems, including a dearth of translators, office equipment, and functional typewriters amid the destruction and looting.

It was at this point that the American soldier’s recently appropriated Continental was drafted back into service, this time in pursuit of justice for some of the worst atrocities ever committed by mankind. The machine was leased to the Allied prosecutors and relocated to the Justizpalast in Nuremberg, where the top 21 surviving members of the defeated Nazi regime would be tried as war criminals.

The quantity of typewritten evidence presented at the trials—200,000 affidavits and sworn depositions of over 360 live witnesses, according to the last living signal-corps typist—all needed to be translated into English, French, Russian, and German. This kept an entire pool of court reporters, secretaries, and typists endlessly busy for the duration of the nearly yearlong proceedings.

In the end, the International Military Tribunal convicted 19 of the top surviving Nazi officials, with Hermann Göring, Wilhelm Keitel, and Joachim von Ribbentrop among the 12 sentenced to death. The verdicts offered little satisfaction—to say nothing of justice—to the millions of victims of the Holocaust and Hitler’s war of aggression. But for the first time, Nuremberg established individual criminal responsibility for wars of aggression, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. If Munich represented kowtowing to authoritarianism and bending principle to the demands of power, Nuremberg represented not a victory for principle, but at least its beginning.

Nuremberg marked the origins of international criminal law, international human rights law, and a generations-long normative shift in international relations that increasingly places the rights of individuals and communities ahead of the prerogatives of states and their leaders. From Israeli reprisals in Gaza to Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, today it is easy to be cynical about international law’s ability to confront unjust military aggression, much less deter it. Still, as a professor of international law, I occasionally glance up from my desk toward the Nuremberg Tribunal Continental that now graces my office shelf to consider both how far we’ve come and how far we have yet to go in the pursuit of international justice.

Of course, over those intervening decades, there were likely few such moral and legal musings surrounding the typewriter itself. After the tribunal’s conclusion, the Continental was returned to the GI who “liberated” it from Nazi headquarters, disassembled, and shipped to his home in Pennsylvania. There, three generations of American schoolchildren used it to type their classroom assignments. Indeed, the soldier’s daughter confided to me as she was showing me to the door that she still makes mistakes when typing on an American QWERTY computer because she learned to type on the Continental’s German QWERTZ keyboard.

So then—can an inanimate tool such as this typewriter be penitent, reformed, and redeemed from the original sin of its creation? Logically, one has to think so … if one believes that an inanimate object can be imbued with original sin to begin with.

And if any artifact of Nazi Germany has the potential to be so redeemed, surely it must be the typewriter. Unlike all the other war trophies of that heinous regime—Nazi battlefield flags, daggers, Lugers, and the like—typewriters are ultimately instruments of human creation, not destruction. Whether it be writing generations of children’s school essays, or the commercial invoices for a thriving mom-and-pop general store, or even the poems and love letters of a young Willy Müller, the typewriter’s very raison d’être is to enable human curiosity and creativity, which is fundamentally the core pursuit of humanity itself. It is that which translates artifact into history.

As cherished, personal, intimate, and lifelong tools of an individual’s passions and creations, typewriters are an excellent repository of such oral histories. Their stories shed new light and perspectives not just into the history of the everyday and the mundane, but also the very real and human connections and consequences of major historical events. The microhistorical perspectives these machines convey are largely absent from our conventional history texts.

Unfortunately, with the passing of generations, we lose ever more of these historical relics themselves, but also the cherished family histories that they can tell. The importance of these mechanical writing machines is not simply in what they are or what they do as artifacts, but ultimately in what they represent within our shared social communities. And what they can represent—and how—is not some innate feature imprinted on the machine at its creation, but a reflection of our ever-evolving and ever-progressing social and political conceptions.