Why Walmart Still Hasn't Crushed the Regional Grocery Store

Traveling across the United States, you can find diversity in the landscape, in the food, in the way people talk.

RELATED: It Only Took About 20 Years for the U.S. to Turn Smokers into Pariahs

And in the supermarkets.

RELATED: Our Books Are Morbidly Obese

RELATED: Americans of Mixed-Up Priorities Fighting over Air Jordans

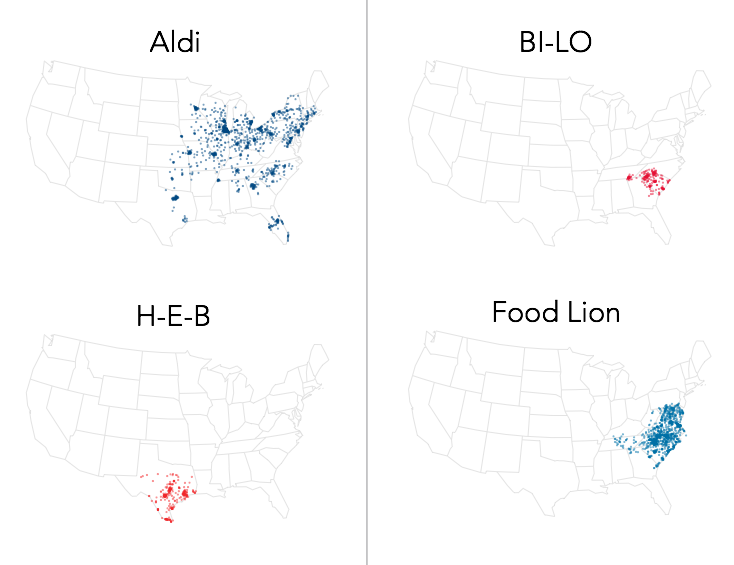

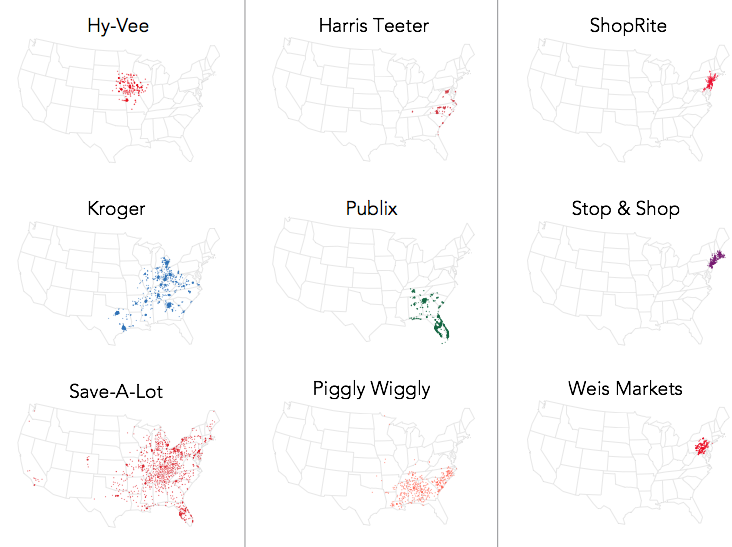

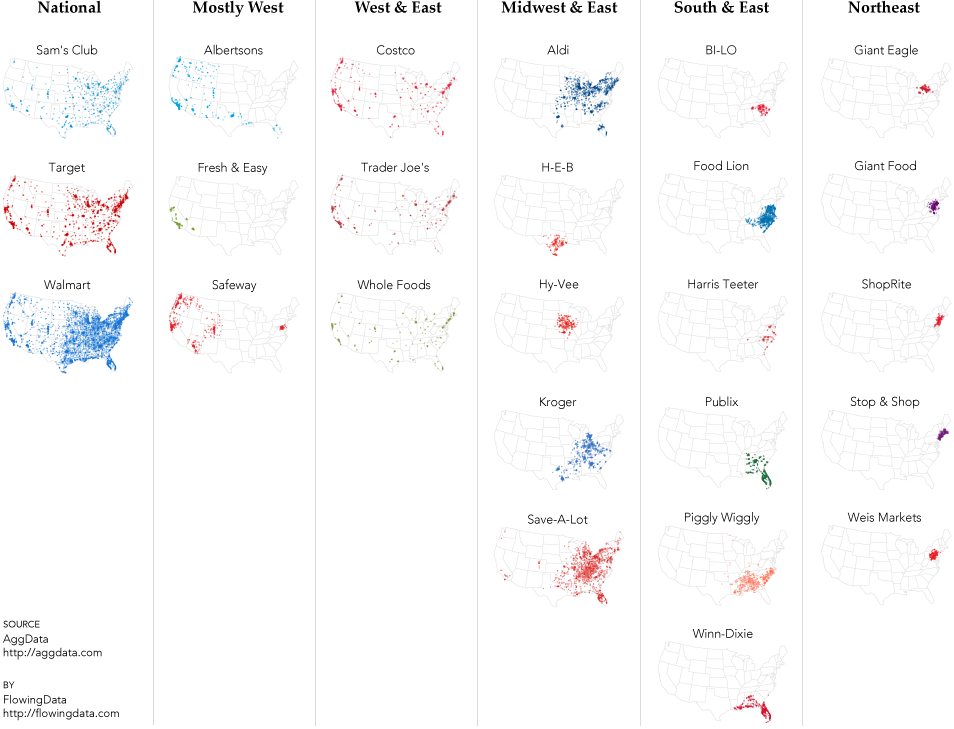

To be precise, you can find a remarkably diverse array of regional supermarkets, their geographic boundaries weird and firm, even though their contents – from cereals to soups – remain largely the same. The above maps, by Nathan Yau at Flowing Data, show the peculiar geography of American supermarket chains.

RELATED: How Walmart Employees Ruined Jon Stewart's Black Friday

MORE FROM THE ATLANTIC CITIES

According to a 2011 report by the U.S. Treasury’s CDFI Fund [PDF], the country’s top ten supermarket conglomerates accounted for only 35 percent of grocery stores and 68 percent of grocery store sales. (That discrepancy is due in large part to Walmart, which sells a lot of groceries in relatively few locations.)

RELATED: The Quest for Gender Equality Stops and Shops

But that statistic doesn’t do justice to the on-the-ground diversity of America's supermarkets, because the “top ten” actually comprises nearly 30 different brands. Familiar names like Target, Winn-Dixie, Whole Foods, and Trader Joe’s aren’t even included in those.

So when Kroger, the nation’s second-largest supermarket company, announced Tuesday that it would purchase Harris Teeter, an upscale brand whose footprint stretches from the Carolinas to D.C., you might have wondered: why didn’t all this happen 70 years ago? Why isn’t the American grocery shopping experience as standardized as the American drugstore visit, or the American coffee stop?

Maps courtesy of Nathan Yau at Flowing Data. Data via AggData.

It once was. In the 1930s, A&P (Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co.) was not just America’s biggest grocery chain; it was the world’s largest retailer. With nearly 16,000 stores, A&P dominated the American shopping experience in a way that defies comparison. To give you an idea, there aren’t half that many Dunkin Donuts in the U.S. today (though the U.S. population has since doubled), and no supermarket chain—not even Walmart—has one-fifth the number of stores that A&P did at its peak.

To some extent, our highly fragmented supermarket landscape is a direct result of post-A&P development. The company adapted to the supermarket age, converting to bigger stores, but its strategy failed to keep up with changing settlement patterns during the birth of suburbia and the age of sprawl. Savvier, smaller, more flexible companies gained a foothold in regional markets, whittling away at A&P’s dominance as a series of poor business decisions sent the former titan towards bankruptcy.

Two things have happened in the intervening decades. First, a series of mergers produced mega-supermarket corporations that combine regional brands, such as Ahold, which owns Giant, Stop & Shop, and Peapod, or Safeway, which owns Vons and Dominick’s. The industry is still quite fragmented, but some of the storefront diversity is illusory.

Second, Walmart emerged as the second coming of A&P, swallowing up huge swaths of the grocery market with its low prices, large inventory, and one-stop shopping. Today, Walmart sells about 30 percent of the groceries in the U.S, and groceries make up more than half of the retail giant’s sales.

Maps courtesy of Nathan Yau at Flowing Data. Data via AggData.

For Kroger, the biggest corporate entity trying to hold ground against Walmart’s march, there is no sense in trying to rebrand regional success stories like Harris Teeter. On the contrary, the brand loyalty they engender and local adaptations they practice may be the best defense against Walmart’s standardized offering.

Kroger buys supermarkets, but it doesn’t change their identities: independent brands produce "a much more satisfied customer than if you were to change all the names to Kroger and homogenize the store experience," Kroger’s CEO David B. Dillon told the New York Times. Indeed, if you shop at Marketplace, Fred Meyer, Fry's, or another of nearly two-dozen regional U.S. supermarkets, you may be unwittingly "Krogering," as aficionados of the Cincinnati-based chain like to say.

It’s not unlike the seemingly peculiar strategy of the American mayonnaise industry: Since Best Foods bought Hellmann’s in 1932, the company has maintained two nearly identical brands of mayonnaise, one sold to the east of the Rockies and the other to the west.