Why do storms keep missing Wichita, and how do meteorologists feel taking the blame?

As a rare “extreme risk” forecast for severe weather loomed in the Wichita forecast a week ago, Mike Smith was not the only meteorologist to be having a particular conversation with God.

“It’s a highly unusual prayer: ‘Lord, please let my forecast be wrong,’ yet that was what I was praying.”

And yet again — whether it was divine intercession or atmospheric conditions or just simple luck — the storms missed Wichita.

That leads to two questions:

First, what’s going on that so many predicted storms seemed to have missed the city this spring?

Second, what’s it like to have thousands of people commenting on what a poor job you’ve done?

“You couldn’t mean me walking in the doctor’s office yesterday and all the people saying, ‘Boy, you really screwed that one up,’ ” Smith said.

“I’ve seen lots of soul searching by meteorologists after a missed forecast, but I’ve never seen anything like this last week.”

The right ingredients

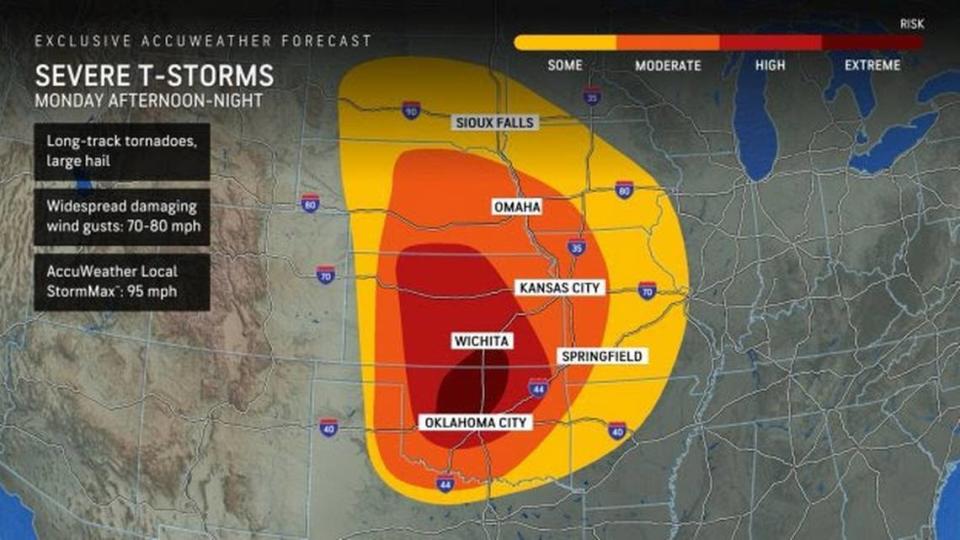

The predictions for May 6 were so dire, even AccuWeather senior storm warning meteorologist Rich Putnam checked his homeowner’s insurance policy the day before.

“All of the ingredients were there for us to see the same level of storms that unfortunately Oklahoma did,” Putnam said.

Putnam believes the storms just happened to strike Oklahoma first, which changed the dynamics in Kansas.

“It’s really hard to determine why those storms went first.”

However, he said he believes the clouds from those Oklahoma storms are “largely what saved us.”

Had those storms happened a half an hour later in Oklahoma, Putnam believes the Kansas scenario would have looked more like its neighbor to the south.

National Weather Service meteorologist Kevin Darmofal said if there had not been unexpected low clouds that prevented Wichita from heating up, “We would have had some pretty rowdy, nasty weather, including tornadoes.”

Darmofal said severe weather is like a recipe when you’re cooking.

Let’s say you’re making chocolate chip cookies. Certain ingredients are so small — such as the teaspoon of baking soda, the teaspoon of salt and the teaspoon of vanilla — but if you leave just one of them out, you have a different cookie. Or maybe even a disaster resulting in an inedible cookie.

Darmofal said it’s the same with storms.

“A lot of different things have to come together to produce the higher-end severe weather.”

Predictability

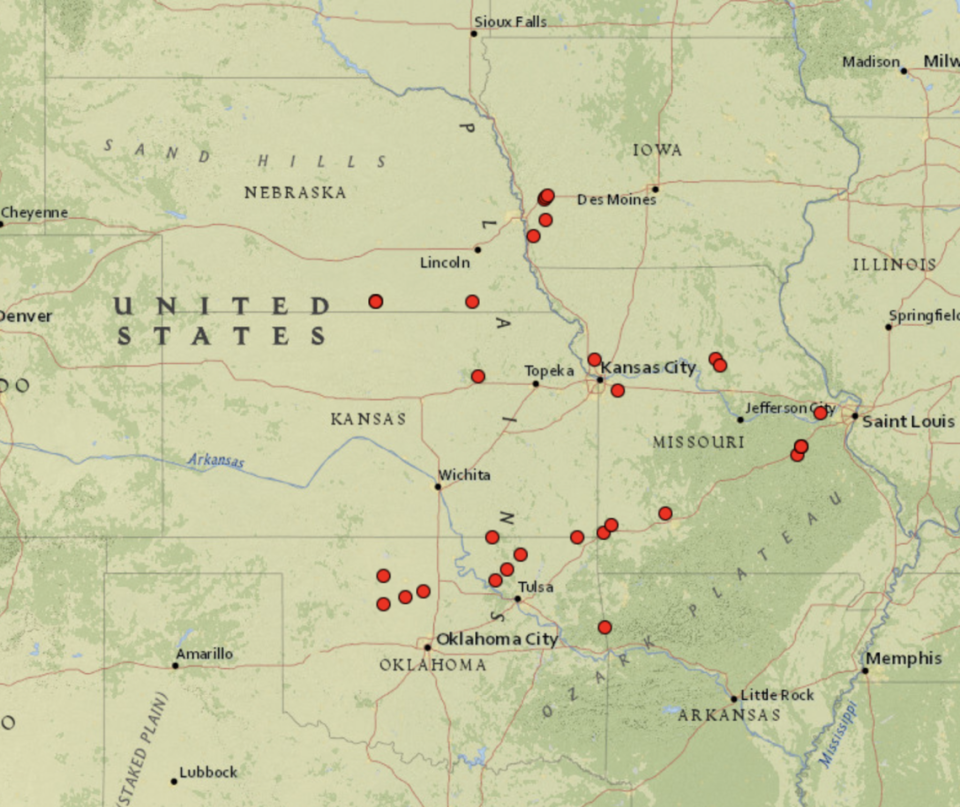

Darmofal said this area has seen a return to more typical storms than in some years and pointed to April, when there were 26 tornadoes in central, south-central and southeast Kansas.

“It’s just that fortunately Wichita hasn’t seen that.”

However, this leads to the risk of people not paying attention the next time around.

Some people may feel foolish for packing “go bags” with items such as water, important documents and first aid supplies in case they had to run to their basements. Others may feel frustrated that they spent hours with their family hunkered down when they could have been out keeping plans.

Naysayers should consider how seriously meteorologists themselves take their own warnings, though.

Putnam was covering the weather from his basement, and he said AccuWeather’s team in Pennsylvania was ready to take over if need be.

“We were nervous.”

Nobel worthy

Though a lot of Wichitans may be asking why storms keep missing the city, Smith said if it were about 25 years ago, “You would be asking yourself, ‘Why do these storms always hit Wichita?’ ”

He said in the 1970s, meteorologist Ted Fujita — for whom the scale of tornado intensity is named — wrote a paper on major tornadoes dating from 1916.

“He found out . . . tornadoes seem to oscillate,” Smith said.

From about 1916 to 1925, storms kept hitting Mississippi, Arkansas and Alabama.

“Then for some reason as we got into the ‘50s, it was right back in what we today call Tornado Alley,” Smith said.

Until this year, there’s been a decade of major tornadoes in the south, but he said now those storms are once again swinging back closer to Tornado Alley, though not necessarily Wichita.

Smith said weather science has its issues, but he said improved forecasting has cut the tornado rate of deaths per 1,000 people by 95%.

“As far as I’m concerned, that is a Nobel Prize-winning accomplishment.”

He said that’s especially so given how difficult it is to predict the weather.

Compare that to say, predicting economic markets. Smith said there are only two ways for markets to go, and yet experts so often get it wrong.

For instance, Smith was vacationing in Hawaii in 2006 when people were celebrating home prices doubling in two years.

“This will end badly,” Smith remembered saying to his wife.

Then the financial crash of 2008 happened.

Smith said weather forecasting has a better success rate.

“Weather science is the best of the predictive sciences.”

Closed for business

For as much as Kansans joke about running to their front lawns when a tornado is heading their way — and many indeed do that — last week was different.

Some schools let out early. Businesses closed. Those that remained open saw far fewer customers than normal.

Could the forecasters have done something different to prevent that?

“We don’t tell people to shut things down,” Darmofal said. “We just say wherever you are, have a plan and be ready.”

It would be fabulous for all concerned if forecasters could simply let people know 15 minutes before a tornado strikes or maybe an hour, but Smith said that’s not how it works.

“We don’t have the skill to do it.”

Yet, anyway.

Smith said it won’t happen in his lifetime, but maybe his children’s.

Smith said one model he saw for last week showed the densely populated north and west sides being hit hard.

“We were talking about a situation that could be just horrible.”

Smith didn’t release that information in part because this model hasn’t always been reliable in the past, but also in part because he didn’t want people to get in their cars to escape a tornado and then get caught in it.

Putnam said an hour isn’t realistic notice since people need time to prepare.

“If you’re only preparing an hour before, can everybody actually get to a safe place in that amount of time?”

In hindsight

Meteorologists have mixed feelings on missed forecasts, especially when so much criticism is leveled at them.

“I can’t say that it doesn’t bother us,” Darmofal said. “To some extent, it comes with the territory.”

And to some extent, the fact that forecasting isn’t an exact science is what makes it interesting, he said.

“We love the weather. We love the challenge.”

He said the science is evolving.

“We’re still learning things about the atmosphere.”

So when expected weather doesn’t materialize, Darmofal said, “You always want to go back and learn.”

Even with the benefit of hindsight, Putnam said that likely won’t change future forecasts given that only slight variables can change outcomes.

“I don’t know that there’s anything we can do differently next time.”

Putnam, who has issued 4,000 tornado warnings in his career, said meteorologists can’t worry what the public will say if a predicted storm doesn’t materialize.

“You really can’t get too caught up in that or you’re potentially not going to make the right decision,” he said. “You want all your decisions to be based on science and the data that you’re given at the time.”

Though Smith and other meteorologists continue to consider what happened last week, Smith said he has no problem with being wrong.

“God may have answered our prayers,” he said. “I’m not sure there’s a better explanation out there.”