Inside the Space Shuttle Challenger tragedy: Why disaster was almost inevitable

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

At 8.15 a.m. on Jan. 28, 1986, New Hampshire social-studies teacher Christa McAuliffe sat with her six fellow astronauts ahead of the launch of the Space Shuttle Challenger from Kennedy Space Center on Merritt Island, Fla., when she was approached by support crew member Jonny Corlew.

As a kid growing up in Indiana, Corlew often picked an apple from the tree in his yard and gave it to his teacher and now he wanted to do the same for McAuliffe, the first teacher to go into space, as Adam Higginbotham recounts in “Challenger: A True Story of Heroism & Disaster on the Edge of Space” (Avid Reader Press).

“McAuliffe raised the fruit to her face with a smile, but then immediately returned it,” writes Higginbotham.

“Save it for me,” she said. “And I’ll eat it when I get back.”

Less than three hours later, McAuliffe and her six crewmates on mission STS-51-L were dead, after Challenger exploded 73 seconds into flight.

“Challenger” follows the key players in a tragedy forever etched on the nation’s consciousness. From the astronauts to the engineers, designers and investigators, it details how the Space Shuttle program not only came about, but also how political cynicism and commercial concerns made a disaster almost inevitable.

Six months prior to the Challenger disaster, booster rocket engineer Roger Boisjoly had written to his managers at NASA contractor and Utah-based rocket manufacturer Morton Thiokol, warning of the dangers of winter launches like Challenger’s, explaining how the joints of the boosters could stiffen and unseal in cold weather, increasing the chances of pressure leaks.

“It is my honest and very real fear that if we do not take immediate action . . . we stand in jeopardy of losing a flight,” he wrote, warning that “the result would be a catastrophe of the highest order — loss of human life.”

On the day before Challenger’s scheduled departure, the forecast for the launch time temperature predicted record cold, with temperatures at the Cape predicted to fall to 23°F overnight — 9 degrees below freezing.

NASA had never launched a Space Shuttle at such a low temperature.

Indeed, a year earlier, on Jan. 23, 1985, the launch of Space Shuttle Discovery was delayed because of freezing weather and when it finally took off, it did so in temperatures of 53°F — the coldest temperature ever recorded for a Shuttle launch.

On the evening of Jan. 27, engineers from Morton Thiokol, including Boisjoly, gave an emergency presentation to NASA revealing concerns about the effect cold weather had on the rocket joints and, in particular, a rubber component, the “O-ring,” critical to preventing gases escaping during liftoff.

“Many of the Thiokol team recognized that the data they had about the behavior of the joints in cold weather was scant; some was contradictory,” writes Higginbotham.

“Even so, it was one that they believed raised enough concerns about the flight safety of the Challengermission to advocate a drastic course of action. “Do not launch.”

Initially, Boisjoly’s insistence to err on the side of caution found favor. The countdown to launch would stop, pending further assessments, and the crew would be stood down until it was safe to proceed.

But when Larry Mulloy, NASA’s project director at Marshall Space Flight Center, was notified, pressure was brought to bear on Thiokol’s management to reconsider.

Fearing Thiokol might lose lucrative NASA contracts, General Manager and Senior Vice President, Jerry Mason, urged his executive team to reconsider, instructing senior engineer, Bob Lund, to “take off your engineering hat and put on your management hat.”

Eventually, a signed document recommending the launch should proceed was faxed to NASA — the first time a contractor had ever been asked to provide written confirmation of a launch decision.

Nobody was happy.

“If anything happens, I wouldn’t want to be the person that has to stand in front of a board of inquiry to explain why we launched,” said Al McDonald, Thiokol’s senior manager at the Kennedy Space Center.

After several delays and with icicles on the gantry, Challenger finally left launchpad 39B at 11.38am on January 28, 1986.

On board were seven astronauts; Commander Dick Scobee, pilot Mike Smith, mission specialists Ellison Onizuka, Judy Resnick and Ron McNair and payload specialists Greg Jarvis and Christa McAuliffe, the successful one of over 11,000 teachers who applied to the Teacher in Space Project.

On the ground, crowds gathered in bleachers three miles from the launch site while the crew’s families and friends, along with VIPs, watched from the roof of Launch Control Center.

Meanwhile, in Concord, NH, seniors at McAuliffe’s school had packed the main auditorium to witness the launch live on the NASA TV feed.

Although it initially appeared successful, suddenly, at 58 seconds into the flight, a flame appeared on the right booster which rapidly reached the fuel tank, incinerating its insulation and rupturing the tank’s membrane.

In seconds, 300,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen was ignited by flames burning at 6,000 degrees as the booster rockets tore free from their mounts and Challenger, still hurtling toward space at 1,500 miles per hour, tumbled from its planned supersonic trajectory.

“The most complicated machine in history began to come apart in flight: its stubby wings ripped away, the cargo bay bursting like a paper bag, the inrushing air pulling the fuselage asunder from the inside,” writes Higginbotham.

The last communication from the cockpit data recorder was from Mike Smith.

“Uh-oh,” he said before the system shut down.

Back at Launch Control Center, the families begged NASA for reassurance. Erin Smith, Mike Smith’s 8-year-old daughter, screamed for her daddy while June Scobee, wife of commander Dick Scobee, went to her husband’s room, only to find an unsigned Valentine’s Day card bearing the words “For My Wife.”

It was an hour before NASA’s Director of Flight Operations, George Abbey, confirmed their fears. “It looks like there has been an explosion,” he told them. “ I don’t believe there is any hope for the crew.”

After witnessing the explosion on TV in Utah, Roger Boisjoly sat in his office and cried.

An entry in his log book read: “I feel real sick about this but I did everything possible to convince them not to fly,” he wrote.

The tragedy dominated Boisjoly’s life.

Diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, he was plagued by sleeplessness and took Xanax for anxiety. On the first anniversary of the disaster, he launched an unsuccessful lawsuit against Morton Thiokol, accusing them of fraud, negligence and manslaughter.

Boisjoly, who died in 2012, aged 73, never worked in the aerospace industry again.

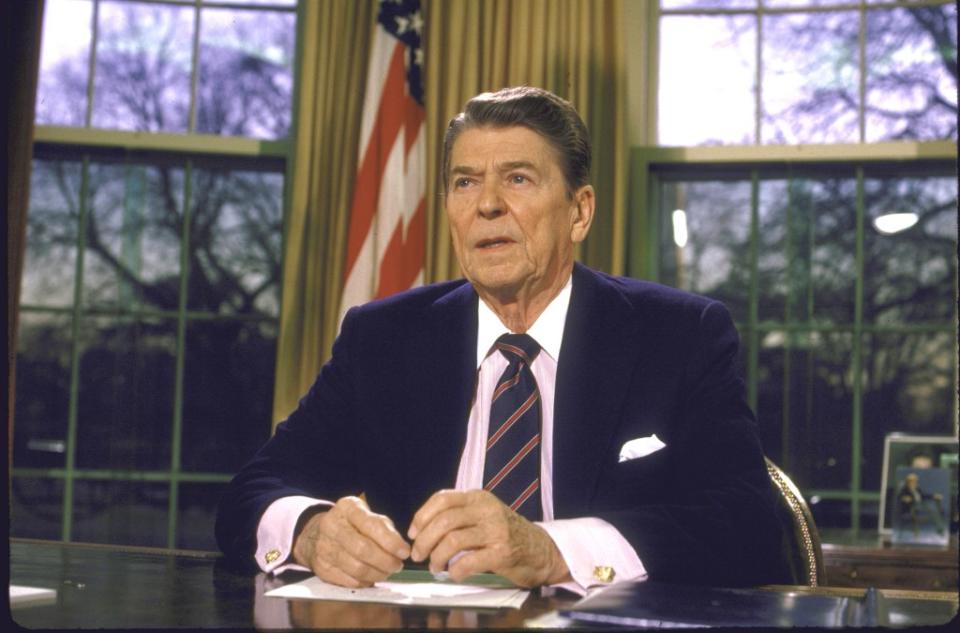

On the evening of the disaster, meanwhile, President Ronald Reagan was due to deliver his State of the Union address but postponed it to speak about the tragedy.

His four-minute speech, written by White House speechwriter Peggy Noonan, drew on the poem “High Flight” by World War II pilot John Gillespie Magee: “The crew of the Space Shuttle Challenger honored us by the manner in which they lived their lives,” the president said.

“We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and slipped the surly bonds of earth to touch the face of God.”