This Is the Real Reason We Need Sleep

Humans spend a third of their lives curled up in bed, and scientists have no idea why. The theories for why animals sleep range from energy conservation, to helping our brains store memories and new information, to being an evolved behavior that keeps us from venturing out into the dangerous night. Scientists have never been able to pinpoint which of these theories, or any others, are really the case.

Turns out there might be a much smaller but no less crucial reason why living critters like us need to hit the hay every day. In new findings published in the journal Molecular Cell, researchers from Israel’s Bar-Ilan University think the main reason we evolved to sleep was that it activates the systems within our body that repair damaged and broken DNA.

DNA in our cells accumulate damage due to UV light, radiation, increased physical and biochemical stress, and even just simple errors our body makes. Our body has repair systems to repair these cracks and flaws in the DNA in our cells, but these repair systems function much more effectively during sleep hours than wakeful ones, presumably because the body can devote more resources to repair.

This is especially true for DNA in our neurons—the most fundamental part of our brains. “During wakefulness, neurons are busy with so many different things,” study co-author Lior Appelbaum told The Daily Beast. The new study demonstrates that the longer you stay awake, the more damage is inflicted on your neuronal DNA, at a rate that’s faster than what your repair systems can accomplish. If your repair systems aren’t allowed to function at optimal settings, the damage can reach dangerous levels that can temporarily or even permanently harm the brain.

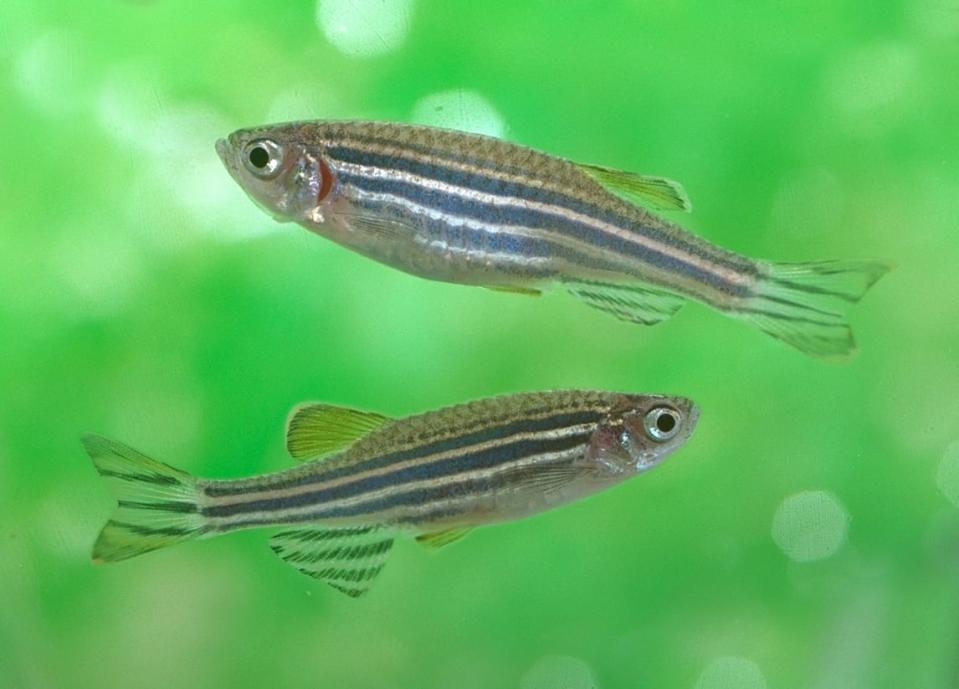

The goal of the new study was to isolate the root of this relationship between sleep and DNA repair. The researchers decided to run experiments on zebrafish, a transparent animal with a similar structure to the mammalian brain, but that is simpler and easier to study. “Using this model, we were able to visualize chromosome dynamics and repair processes in neurons in live fish during sleep and wakefulness,” said Appelbaum. “Zebrafish are also a great model for genetic manipulations, so we could develop all the necessary molecular and imaging tools.”

Zebrafish. Though prominently striped on their bodies, their heads are quite transparent, and the organs inside are visible.

The study had two major parts. In the first, the Bar-Ilan team used tools like irradiation and drugs to induce DNA damage in zebrafish, and found that that increased damage led to an increased need for sleep so that the body could run repair systems. The minimum amount of sleep needed was six hours—anything less meant that the zebrafish could not adequately repair their DNA.

In the second part, Appelbaum and his team used gene-editing tools to play around with a protein called PARP1, which tells the body what parts of the cell’s DNA need repair. The researchers found that increased amounts of this protein in the zebrafish promoted more sleep, and therefore more sleep-dependent repair. Inhibition of PARP1 meant the fish didn’t go to sleep, and therefore didn’t repair their DNA well. A separate set of trials on mice confirmed the PARP1 connection.

“I think this is an interesting paper that extends prior studies on the relationship between sleep and DNA damage,” Mark Wu, a neuroscientist and sleep researcher at Johns Hopkins University who was not involved with the new study, told The Daily Beast. “In addition to its identification of potential molecular mechanisms, the study also provides data from both fish and mice, which is a strength of the study” and means the findings more likely apply to all animals, including humans.

Appelbaum also thinks there are some pretty big implications for how we can approach neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, for which sleep disturbances are a symptom. “Maybe accumulation of sleep deprivation reduces cell health and is one of the causes,” he said. If true, modulating PARP1 activity could theoretically be a way of treating these diseases.

Wu added that “from a broader perspective, this builds on a growing body of research on the relationship between stress and sleep. As far as the take-home message, it is yet another example of the importance of getting enough quality sleep.” Many studies suggest that adult Americans get an average of less than six hours of sleep at night, below the recommended seven to eight hours.

So if you were looking for another reason to stop bingeing Squid Game and get to bed earlier, then you can add the health of your DNA to that list.

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.