Why Was The Relationship Between Black Americans and the O.J. Simpson Verdict So Complicated?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In October 1995, the studio audience of “The Oprah Winfrey Show” strained their necks to get a better view of the screen.

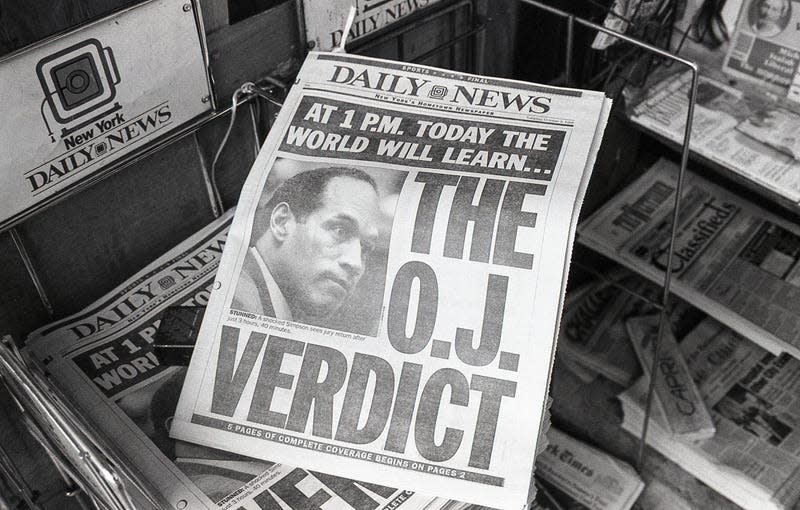

In mere moments, jurors would hand down a verdict in the trial of O.J. Simpson, who stood accused of murdering his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman.

“By the time you all see this, you will already know the O.J. verdict,” says Winfrey, facing away from her audience. “But we just like the rest of the country, are waiting to hear it live for the very first time.”

The camera flashes to the faces of two women. One Black, one white. Both waiting with bated breath for a decision. “We the jury in the above entitled action find the defendant Orenthal James Simpson not guilty of the crime of murder,” reads the lead juror.

Immediately, a group of Black women erupt from their seats, cheering on the verdict. Conversely, a scattered group of white women bow and shake their heads in noted silence.

The moment, which has re-emerged as a cultural touchstone in the wake of Simpson’s death, has come to represent the racial divide over the verdict: White America was horrified while Black America celebrated.

It’s easy to read the over-the-top studio reaction as callousness for the tragically young victims and their families who wept as the verdict was read.

Brown Simpson, 35, allegedly survived harrowing abuse at the hands of her ex-husband, Simpson, before she was brutally murdered in her home. According to the autopsy report, one of her stab wounds was so deep she was nearly decapitated. Goldman, 25, was merely returning a pair of glasses left behind at the restaurant where he was a waiter when his life was cut short. He was stabbed over a dozen times.

Regardless of how terrible the LAPD was at the time, no one credible claims that Goldman or Brown Simpson deserved what happened to them. So, should we understand Black Americans’ reaction to the verdict as pure callousness to the suffering of Goldman and Brown Simpson and adoration of “The Juice,” or is it deeper?

Charles Coleman Jr., a civil rights attorney writing for MSNBC, sais the reaction to the Simpson verdict can be primarily understood as a reaction to the Los Angeles Police Department.

“It’s not hyperbole to say that the heat from embers from the 1992 Los Angeles riots, sparked by the acquittal of the four officers who beat [Rodney King] on almost all charges, could still be felt in the air in 1994 and 1995 when members of the Los Angeles Police Department investigated Simpson and testified during his trial,” he wrote. “Black Angelenos (and Black people across the nation) believed the LAPD to be the racist enforcement arm of a bigger system that was not only unjust but went out of its way to target Black people.”

The fact that LAPD Detective Mark Fuhrman, a key witness, was caught lying about using an anti-Black racial slur further shaped the public discourse that this case was about racist policing, he argues. “The Fuhrman tape and the portrait the defense painted of Fuhrman was the prompt to root against the system, even if there was a suspicion that O.J. may have done it and we, in turn, were rooting for a cold-blooded killer,” wrote Coleman.

Ta-Neshisi Coates analyzing the case and Black America’s reaction to it for The Atlantic in 2016, came to a similar conclusion. “Racism formed the substrate of the defense’s case: The notion that the LAPD might frame a black man was completely within the realm of possibility for black people in Los Angeles,” wrote Coates.

The abuse that Brown Simpson, in particular suffered, was an afterthought, argues, Coates. “Nicole Brown was proof to the world that Simpson, among the millions of black men caught in the maze of American racism, had risen above it,” he wrote. “What sort of abuse—verbal and physical—was going on behind the mansion gates, almost no one, black or white, guessed. Or much cared.”

While Coates contextualizes the reaction to the verdict within its racial context, he doesn’t celebrate it. Instead, he warns that unless something changes, we’re doomed to repeat it.

“The problems that moved those crowds of black people to cheer for a murderer remain,” he writes. “The same anger, the same fear of police remain. The elements that interacted to turn the Simpson trial into a spectacle are still with us, so that today, two decades after Simpson was acquitted, “the audience for escapes,” in Doctorow’s words, “is even larger.”