Why Idaho Hasn't Stopped Shaking Since March 31

Months after a magnitude 6.5 earthquake struck Idaho, the southern part of the state is still shaking.

Aftershocks are clusters of seismic activity that occur along the same fault as a major earthquake.

In some cases, aftershocks can occur centuries after the main earthquake.

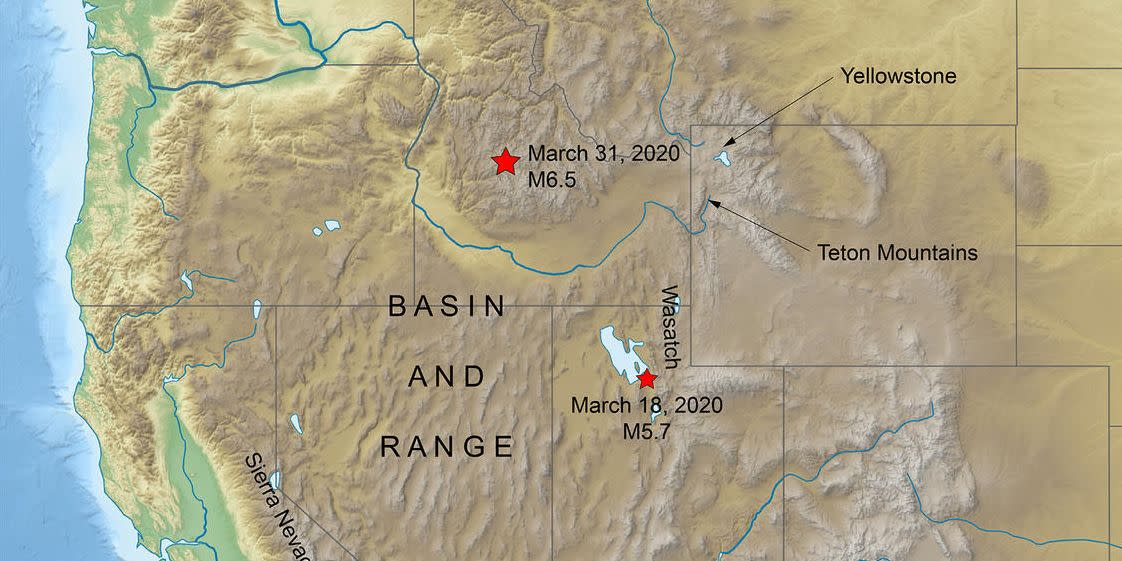

On March 31, a 6.5 magnitude earthquake rolled through Idaho's Sawtooth mountain range, northeast of Boise. It was the second largest earthquake to strike Idaho, according to the Idaho Statesman. (The strongest temblor in Idaho history, 1983's Borah Peak earthquake, registered as a magnitude 6.9.)

Well I have video of my perspective of the earthquake in Idaho. pic.twitter.com/wk8I0JDgzc

— Unironically Confused (@austriescrypto) April 1, 2020

But the region hasn't stopped shaking since. The area has experienced a string of aftershocks in the months following the quake, some registering as high as magnitude 4.8. The shaking has been so strong, in fact, that a popular beach along Stanley Lake in the Sawtooth National Recreation Area has sunk into the water.

"The most probable cause for the 'disappearing' of the inlet delta is a combination of liquefaction and compaction of saturated sediments and some possible sliding and later spreading on the delta toward the deeper part of the lake," Claudio Berti, director and state geologist of the Idaho Geological Survey, said in a statement.

The March 31 earthquake occurred 16 miles north of the Sawtooth Fault, a 40-mile stretch of fault line discovered nearly a decade ago. Geologists have largely believed the fault was inactive, but the latest round of quakes have reinvigorated interest in the region.

Geologists are puzzling over exactly what caused an earthquake in the otherwise quiet region. Some researchers suspect the Sawtooth Fault is actually longer than expected. Others believe the fault is now taking advantage of openings in Earth's crust and is slowly pushing north. One theory suggests energy from the Sawtooth Fault could have jumped to a nearby unknown fault, spurring the recent series of earthquakes.

For now, the race is on to collect more data about the region, so that geologists can paint a clearer picture of what's happening below surface. In addition to gathering seismic readings and analyzing soil samples, researchers will use LIDAR to hunt for signs of movement in the area.

What's With All the Shaking?

In the aftermath of a major earthquake, it's common for a series of smaller earthquakes, called aftershocks, to occur. Aftershocks, which usually originate on the same fault line, can last for days, weeks, months and even years following the main shock. The larger the earthquake, the longer it'll take the fault to get all that shaking out of its system.

Waves from the #IdahoEarthquake rolling through Alaska and the lower 48. Data from the @IRIS_EPO Data Management Center. Thanks guys for making it so easy to access seismic data! pic.twitter.com/M7aGex1zyV

— UMN Seismology (@UMNseismology) April 1, 2020

In some cases, seismic energy along a fault line will build up over a long time. A 2009 paper in the journal Nature suggested earthquakes that occur far away from tectonic plate boundaries may be lingering aftershocks from temblors that happened centuries earlier. The pace at which two tectonic plates slide past each other could dictate how long aftershocks may last, with slower movement leading to longer last bursts of related seismic activity.

Scientists are currently working on ways to use artificial intelligence to forecast where aftershocks may occur. A team of researchers used 131,000 reported earthquakes to train a neural network to accurately forecast aftershocks, according to a 2018 paper published in Nature.

So ... What About Yellowstone?

Fear not: Even though Idaho is still rumbling, that doesn't mean Yellowstone is headed for an eruption.

Idaho lies along the northern edge of a geologically active region called the Basin and Range Province. This region, which spans eastern California to Utah and down into Sonora, Mexico, has been stretched taught over the past 20 million years, creating a series of wide valleys and vast mountain ranges. It's also chock full of old seismic faults—just like the one that sprang to life on March 31.

Idaho is part of the Basin and Range tectonic province. Everything west of the Wasatch Mtns. is getting slowly stretched out as a bit of North America tries to cling to thePacific plate

— Dr. Lucy Jones (@DrLucyJones) April 1, 2020

Yellowstone last erupted 70,000 years ago, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Since then, there have been over 10,000 magnitude 6-or-higher earthquakes in the western U.S. While the temblors can occasionally spur rumblings at the national park's geysers—as a magnitude 7.3 earthquake in Colorado did in 1959—they aren't likely cause a volcanic eruption.

You Might Also Like