Why it's harder to care for a disabled child in NJ: State funding is 'broken,' parents say

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In New Jersey, families of children with severe disabilities have two main options for their care: a group home system that many see as unsafe and understaffed − or paying for care at home.

But there's a catch: Thanks to state rules, they won't be able to pay their home aides nearly as much as group-home agencies can pay their staff.

That's unfair, disability advocates say, and forces families into institutionalized care. It's a discrepancy the community − and Gov. Phil Murphy's own disability watchdog − are urging the state to rectify as budget negotiations continue.

The funding allowed for at-home care is "divorced from reality," said Paul Aronsohn, New Jersey's ombudsman for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. "It's not much money, and it makes it harder for families to find staff."

What is self-directed care?

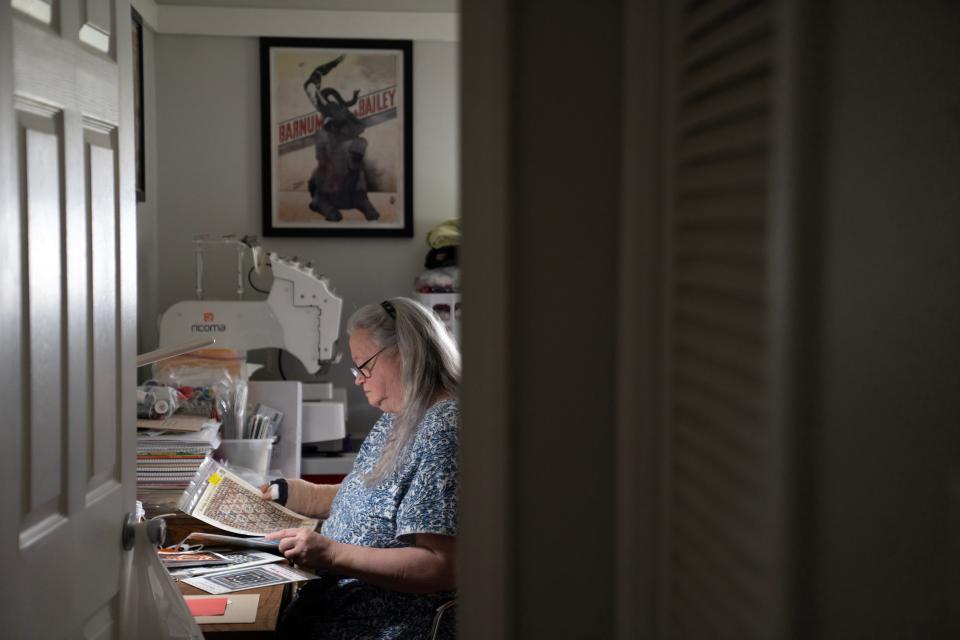

Families who opt for at-home care − officially known as "self-directed" − can tap into a $2.4 billion pool of state and federal aid to hire people to take care of their adult children. Parents like Karen Monroy, an advocate for this approach, said they choose that route because of its promise for more personalized, compassionate care.

"People who are self-directing are doing it for two reasons," said Monroy, who lives in Flemington with her son with autism. "They realize how horribly broken the provider agency system is, and they're terrified of the abuse.“

Monroy said she chose to keep her son out of the system after he was abused at a therapy program in 2013. Newton’s Jennifer Worley made a similar decision for her daughter, Elizabeth.

Her 31-year-old with intellectual disabilities has suffered more than once in homes run by private companies, including physical and sexual assaults, Worley said. Too often, she said, Elizabeth lived in squalid conditions, was rarely taken outside and was surrounded by aides ill-equipped to care for her.

Worley decided to find a place for her daughter to live and hire aides herself. She found a house in her Sussex County town, close to family, and staffed it with eight people, including Elizabeth's sister, who serves as a live-in aide.

"She has her family around her. She is just happy," Worley said. "She has activities, she has a lady that comes in and plays games with her three days a week, takes her on walks, cooks with her. She's out every day.” The setup also means Elizabeth gets to go to church three times a week, her mother added.

It's a success story, but one made harder to accomplish because of what many see as an arbitrary cap placed by the state on what it will pay for self-directed care.

'Stark inequities' in disability funding

Under New Jersey rules, people who want to hire their own caregivers will be reimbursed by the state for up to $25 an hour per aide, while group home agencies can get up to $57 an hour.

"The inequities between the two models are stark," Monroy said.

The money, overseen by the state Division of Developmental Disabilities, comes out of the Community Care Program, which is expected to spend more than $2.4 billion in the 2024 fiscal year. About $1.5 billion of that will go to an estimated 8,000 residents in group homes or other congregate-care settings, with the rest going to about 6,100 who self-direct.

The $25 per hour maximum, set by the state four years ago, is based on wage data for the cost of at-home care, including statistics from the federal Labor Department, said division spokesman Tom Hester. He noted that it can rise to as much as $48 an hour when a person's medical needs are extreme.

Hester didn't respond to a question about when or whether the state might reassess its cap. But he emphasized that the Murphy administration has invested over $1 billion in recent years to enhance wages across a variety of caregiving professions. That's included tens of millions of dollars for aides who work in group homes in an effort to ease staffing shortages and high turnover, he said.

More: NJ program puts focus on women with disabilities and their health care

"DDD also permits consumers to hire family members including parents and spouses, which further assists in delivering individualized care and combatting workforce challenges," added Hester, noting that is "a flexibility not always available in other states."

Group homes face higher costs

The $57 an hour group homes get from the state includes expenses beyond worker pay that families don't face at home, said Valerie Sellers, CEO of the home-provider trade group New Jersey Association of Community Providers. That includes administrative overhead, health insurance, and other operational expenses, she said.

The actual wages that aides receive are low across the board, she added, rejecting the idea that group homes can outbid families for good care.

"Most agencies, the highest that I've heard is $23 an hour and that is from an agency that takes the most complex, behaviorally challenging individuals," Sellers said. "Most of the average salaries are between around $17.50, maybe $18.50."

Aronsohn challenged that explanation, arguing it was “hard to believe that these agencies have such exorbitant overhead costs." He urged the state to fix the pay discrepancy in both his 2019 and 2021 annual reports. It's still a problem, he said in a recent interview.

The policy doesn’t take into account overhead expenses incurred by families such as training and background checks, Aronsohn added. It leaves private payers “at a disadvantage by making it much harder for them to compete with home health agencies, who can provide higher salaries and benefits to staff.“

The pay limit "does not take into account the fact that some individuals need a higher level of care than can be provided by someone making only $25 per hour," Aronsohn wrote. "The threshold therefore not only makes it difficult to hire a professional with the right mix of expertise and training; it makes it difficult to retain them."

Additional money can be granted for families who need "special medical or behavioral support," noted Hester, the state spokesman. That can push the hourly wage they can offer up $48 if specialized home care is required by someone like a registered nurse.

'Take that job and shove it!'

But families interviewed for this story spoke of having to fight the state for bigger budgets and the difficulty of funding proper staffing for people with more severe disabilities. Aronsohn said it's "not easy to get" that extra money, especially under the state's strict guidelines.

Picture someone on the autism spectrum who has trouble controlling their behavior, Aronsohn said. "It's not that you need a medical nurse. [You've] got severe, challenging behaviors, like self-injury or destruction of property," he said. It's a hard job, but not one that requires a nurse, Aronsohn said.

"They're going to say, 'Twenty-five dollars an hour? You could take that job and shove it!' You're not going to get a nurse to do that kind of work."

Monmouth County resident Gary Brush’s daughter Emily, who has “severe” cerebral palsy, lives that reality every day, he explained in a wavering voice.

"Someone like my daughter, who needs 24-hour care, someone sitting right next to her, taking her to the toilet, feeding her, bathing her, making her food: They put on the same $25 an hour cap, regardless of the needs of the individual, that makes no sense," Brush said.

It's "nearly impossible to hire the skilled people needed for complicated care" like his daughter's, Brush added. He's been fighting for 30 years to keep her out of a group home, he said, but it's a fight that keeps getting harder.

How to close the gap

Aronsohn has proposed several reforms.

Equal treatment between families and provider agencies: There should be no artificial pay caps for families, he said. Instead, families should be limited only by their assigned budgets and state oversight.

More transparency in how salaries are set for self-directed employees. Aronsohn called for an "intensive review" process for any denied salary requests, involving in-person meetings with state officials.

An advisory committee, composed of “at least 50%” of self-directing families.

“Self-direction is often the only choice for some families, who fear placing their loved one in a state-licensed residence or who are effectively forced from such a residence due to a lack of adequate supports," Aronsohn said.

Gene Myers covers disability and mental health for NorthJersey.com and the USA TODAY Network. For unlimited access to the most important news from your local community, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: myers@northjersey.comTwitter: @myersgene

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: How NJ makes it harder for parents to care for disabled kids