Why the GOP Tax Bill Is So Unpopular

President Donald Trump says he doesn’t want to cut taxes on the rich. His Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said he doesn’t want to cut taxes on the rich. The Democratic Party says they don’t want to cut taxes on the rich. Americans say they don’t want to cut taxes on the rich.

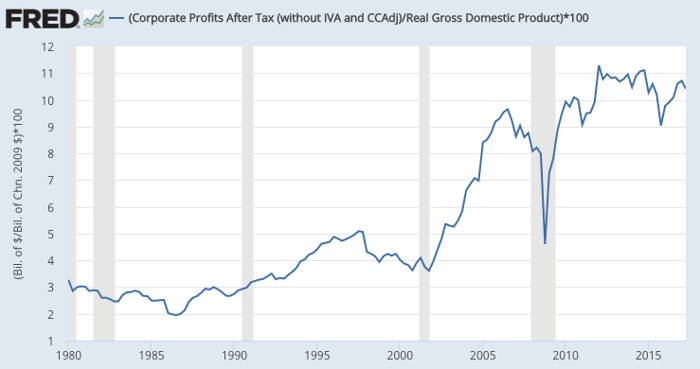

The House and Senate Republican tax bills are taking a different approach: They are cutting taxes on the rich—significantly. Their plans would slash the corporate tax rate by almost half, cut taxes on pass-through income for smaller businesses, eliminate the Alternate Minimum Tax, and erode the estate tax, all of which disproportionately help rich families. This comes at a time when post-tax corporate profits as a share of GDP have hovered at a record-high level for the last seven years, and the top 1 percent's share of total income is higher than any time in the second half of the 20th century.

Recommended: The Departing Consumer-Finance Director Moves to Thwart Trump

Nearly 50 percent of the benefits of the Senate tax cut would go to the top 5 percent of household earners in the first year of the law, according to the Tax Policy Center. By 2027, 98 percent of multimillionaires would still get a tax cut, compared to just 27 percent of households making less than $75,000. It’s no wonder then that the GOP tax bills are now among the least popular pieces of major legislation in modern history, with the public rejecting it by a two-to-one margin. Other than Republicans, all party, gender, education, age and racial groups disapprove of the bill.

Recommended: The Nationalist's Delusion

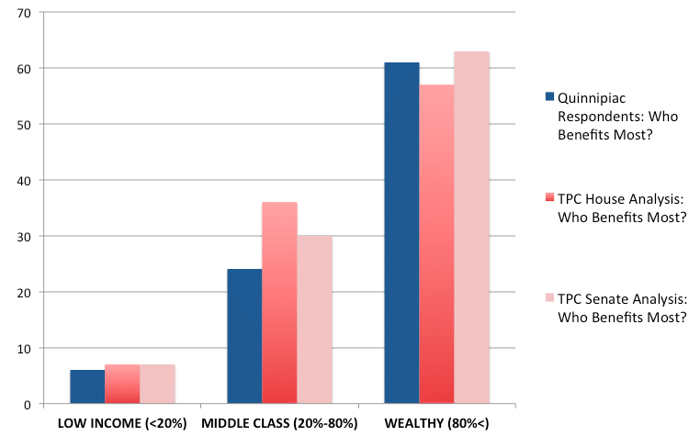

In an almost eerie way, the unpopularity of the bill is an almost perfect reflection of its distributional effects. In a recent Quinnipiac poll, about 60 percent of respondents said that the wealthy would benefit the most from tax cuts compared to just 6 percent of the poor. In fact, TPC analysis finds that about 60 percent of the tax benefits of the House and Senate bills would go to the top quintile, while the poorest 20 percent would receive about 6 percent.

Share of Quinnipiac Responses vs. Estimated Distributional Effects of Tax Bills

There is no parliamentary rule requiring that major tax legislation must be a means of enriching the already affluent. Lawmakers could increase take-home pay for non-rich families immediately with a payroll tax cut. They could expand the Earned Income Tax Credit and permanently extend a larger Child Tax Credit that grows faster than inflation. They could permanently increase the "refundability" of tax credits to help lower-income families.

Recommended: Females' Eggs May Actively Select Certain Sperm

But they’re not doing any of that. They’re cutting taxes for the rich. And there are two reasons why.

The first is that Republican politicians, whose campaigns are often financed by wealthy conservative donors like Sheldon Adelson and the Koch family, are worried that a failure to cut taxes on corporations will have a detrimental effect on contributions from the party’s corporate-libertarian wing. “My donors are basically saying, 'Get it done or don't ever call me again,'" Representative Chris Collins, a New York Republican, told The Hill. The “financial contributions will stop" if the GOP fails to deliver corporate tax cuts, Senator Lindsey Graham, a Republican from South Carolina, told NBC News. "The donor class … has concluded that the inaction of this administration and Congress is totally unacceptable,” Josh Holmes, the former chief of staff to Senator Mitch McConnell, told CNN. “(Donors) would be mortified if we didn’t live up to what we’ve committed to on tax reform,” Steven Law, the head of Senate Leadership Fund, a super PAC, told the New York Post.

There are so many quotes from Republican politicians foretelling donor retribution that it’s tempting to say the party’s legislative problems are simply the result of a plutocratic donor class demanding laws that are out of step with the American public. Indeed, even Republican voters don’t stand behind them. In a 2015 Pew survey, more than half of Republican voters said they were bothered by corporations not paying enough taxes.

But there is another reason why the Republican tax bills, like the party’s “repeal and replace” bills, have faced such massive national unpopularity. Spurred by a donor class that is seeking radical changes to the budget, the party has already rejected the moderate conservative solutions to healthcare and corporate tax policy. As The Atlantic’s David Frum wrote this week, “the broad outline of tax reform seems obvious: Lower corporate rates to somewhere between 25 and 30 percent, the developed-world norm [and] tighten collection so that the rate is actually paid.” But that very idea has already been proposed by President Barack Obama in 2012. Republicans immediately rejected it, just as they rebuffed the president’s inclusion of ideas hatched at the conservative Heritage Foundation in the Affordable Care Act. Since the Republican Party has already rejected the reasonable conservative frameworks for health care and corporate tax policy, all that it’s left with is the land of the unreasonable.

Read more from The Atlantic:

This article was originally published on The Atlantic.