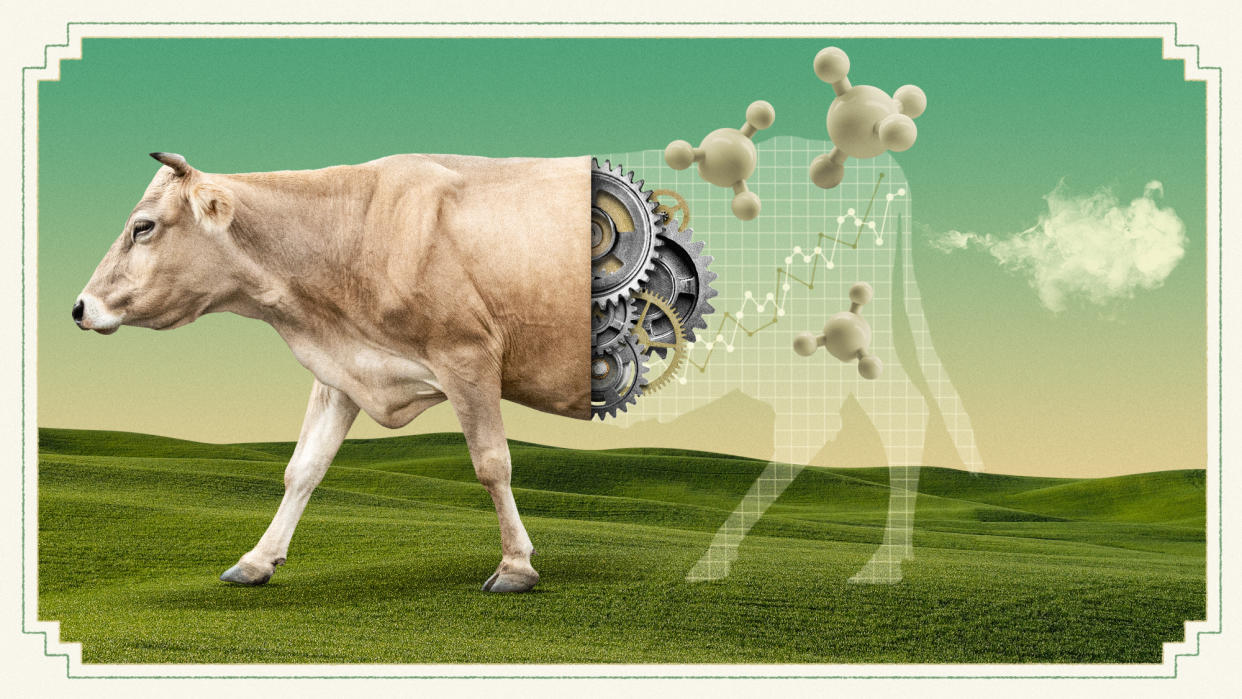

Why curbing methane emissions is tricky in fight against climate change

Marks and Spencer is to invest £1 million on a diet plan for dairy cows in the latest bid by big business to curb methane emissions.

The retailer is aiming to "slash" up to 11,000 tons of greenhouse gas emissions annually by making the burps and farts of its 40 herds of pasture-grazed milk cows "more eco-friendly", said the Daily Mail. M&S claims that switching them to a diet derived from mineral salts and a by-product of fermented corn will reduce methane production during digestion, cutting the carbon footprint of the cows' milk by 8.4%.

How much damage does methane cause?

Aside from carbon dioxide, methane is the "most significant" contributor to climate change, said New Scientist. Methane occurs naturally but is also caused by humans, most commonly during fossil fuel production, "due to leaks from wells, coal mines, pipelines and ships".

Landfills are also a significant contributor, because of methane released by decomposing food waste, but the second biggest emitter is through the burping and defecation of livestock. With "around 1.5 billion cows on the planet being raised as livestock", said Vox, the production of meat and dairy is a "climate problem we've struggled to solve".

Methane is responsible for "about a quarter of overall warming", said New Scientist. Although it does not stay in the atmosphere for anywhere near as long as carbon dioxide, methane is "around 30 times more potent than CO2" – and there has been a "steady rise" in methane emissions for almost two decades. The long-lasting effects of CO2 will "increasingly dominate over time", but tackling non-CO2 gases such as methane will bring a "significant near-term effect".

How is it being combatted?

Given that methane only lasts in the atmosphere for around 12 years, many see it "as low-hanging fruit for climate solutions", said The Associated Press (AP). At the UN's Cop26 climate summit, in 2021, a "global methane pledge" was launched to combat rising emissions. Yet while 155 countries have signed up, the pledge does not include an agriculture target and little improvement has been made.

At last year's Cop28, further plans were announced to try to reduce methane emissions by 30% before 2030, with more than $1 billion in extra funding and reduction commitments by leading methane producers.

But some countries, notably India, have yet to commit to any such pledges. India is the "world's largest milk producer", said AP, and is home to around 303 million bovine cattle that are responsible for around 48% of all of the country's methane emissions.

There are some promising practices that could help stem the flow of agricultural methane, including "new breeding and feeding techniques", said the BBC. But it is human diets, and the consumption of meat and dairy, that are the "ultimate blind spot holding up methane reduction".

What next?

An independent monitoring business is using satellites to determine the amount of methane in the Earth's atmosphere and where the biggest emissions are coming from, with a primary focus on leaks from oil and gas fields.

The data collected is being fed back to "scientists, policymakers, industry and the public", said Gina McCarthy in The Guardian, and demonstrates how "collective efforts" could help "avoid the worst impacts of the climate crisis". What has become clear is that cutting methane levels "is the most efficient way to slow global warming in our lifetimes", and that "we have the chance – and the obligation – to do so".