Why This Church Is Providing 'Sanctuary' To Undocumented Immigrants

At a time when undocumented people nationwide are living in fear under President Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant policies, one church continues to lead the way in supporting them.

Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, Arizona, helped launch the “sanctuary church” movement in the 1980s, when places of worship across the country helped harbor Central American migrants facing the threat of deportation after fleeing violence in their countries. Southside was one of the first to publicly offer sanctuary and helped an estimated 14,000 immigrants throughout that decade, ABC news reported.

The Tucson church has also been part of the movement’s resurgence since 2014, prompted by former President Barack Obama’s record deportation numbers. Around 400 churches nationwide declared support for undocumented immigrants, with some, including Southside, providing physical haven to people at immediate risk of deportation.

This year, in response to President Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies ― including a crackdown on so-called sanctuary cities and rescinding the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program ― the number of churches offering sanctuary has more than doubled to over 800 nationwide.

Days before Trump’s inauguration, Southside gathered with local congregations to promise sanctuary to undocumented people facing deportation in the coming years.

“We’re living under an administration that is feeding off of a narrative of fear of the immigrant,” Rev. Alison Harrington, Southside’s pastor since 2009, told HuffPost. “It’s work we don’t feel like we have a choice in. Our commandments are really clear: Welcome the stranger, work for the oppressed. God’s not like: ‘Well, if you feel like it.’”

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement designates churches, along with schools and hospitals and events like funerals and political protests, as “sensitive” places that agents should avoid when carrying out arrests. Living within the walls of a place of worship can help immigrants avoid the threat of deportation, though it’s not a guarantee.

Since Trump’s election, at least a dozen people have sought sanctuary in churches nationwide. In one high-profile case, undocumented community organizer Jeanette Vizguerra took shelter in a Denver church for 86 days.

But sanctuary work isn’t limited to providing a physical haven, Harrington said. While “sanctuary churches” are meant to provide housing to people at risk of deportation, most won’t actually be called upon to do that.

Southside itself has not housed anyone yet this year. But the church still offers “sanctuary” to undocumented folks in the broader sense of the term, Harrington said, by providing community members with support through free legal clinics, coordinating child care and running the Southside Worker Center, where undocumented people get training on workplace rights.

“[Southside] does so many things ― whenever you have a need, you ask them, they help,” Eleazar Castellanos, who is undocumented and was a lead coordinator at the worker center for two years, told HuffPost. “If they can’t, they connect you with someone who can. It’s not necessary to be undocumented or in a situation of deportation. You can go, whoever you are.”

Harrington says one of her biggest challenges has been communicating to new churches joining the movement that “sanctuary” entails supporting undocumented folks in the larger sense, not just offering last-resort housing.

“We know it’s not enough to say, ‘Come to our house of worship and you’ll be safe.’ We have to also work in our communities to make sure people are safe in their workplaces, in their homes,” Harrington said. “We’re telling congregations nationally it’s not just ‘Check a box and say you’re a sanctuary and feel really good about yourself.’ How do you go meet with people in your community who are already doing the work and stand alongside them?”

For Harrington, that has meant attending demonstrations against anti-immigrant policies alongside undocumented people, among other things. And because the immigrant community is diverse, it also means making her church a welcoming space for all groups who may be marginalized.

“My vision is every church as a sanctuary space, defined broadly,” Harrington said. “So trans folks are welcomed, and that means having bathrooms appropriate to welcome them. And every church has a ‘Black Lives Matter’ sign up front.”

“People feel like we have to do something,” she added. “[Otherwise] we won’t be able to look our grandchildren in the face.”

Another challenge has been trying to ensure that churches don’t draw too much attention to their own reverends ― who in many cases are white and almost never undocumented ― rather than to the undocumented people most affected by Trump’s policies, who are often the ones organizing in the wider community.

“I think the hardest part is getting white people who are involved to appropriately engage in the work, helping them deconstruct whiteness and privilege,” Harrington, who is white, told HuffPost. “It’s hard; I have to constantly reflect on what is my appropriate role. A lot of times when I’ve done this work, I should have stepped back more.”

“[But] this moment is not one for ideological purity ― we have a lot of people entering the movement who haven’t been engaged before, and we can’t be shaming them for not using the right language,” she added. “Each one of us, especially who are white, have entered the work in some way ― [when] we failed, others were gracious. If we’re allies, it’s never going to be perfect, and this moment is too important to worry about perfection.”

Castellanos said the issue of white people putting themselves center-stage in sanctuary work hasn’t concerned him much when it comes to Southside.

“I’m blessed by that church,” Castellanos said. “I love those guys for all the effort and work they’ve done.”

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

MORE FROM LISTEN TO AMERICA

24 Books That Will Help You Understand America

How Far Will Your Rent Dollar Stretch Around The Country?

Check Out The Full Schedule For HuffPost's Listen To America Tour

Also on HuffPost

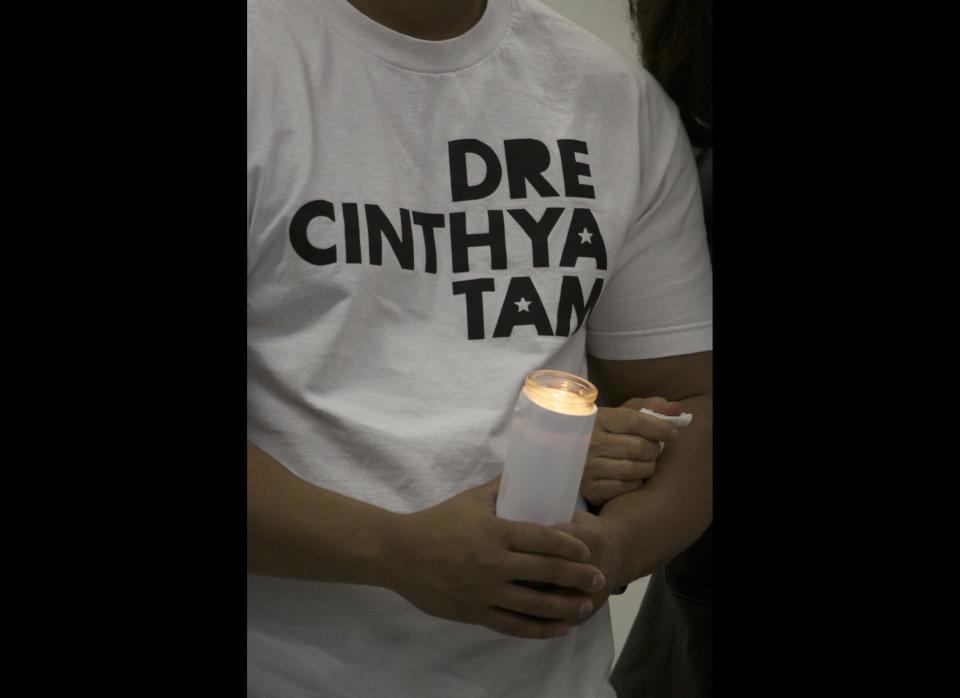

Photograph: Cinthya Felix and Tam Tran

Photograph: Mourning

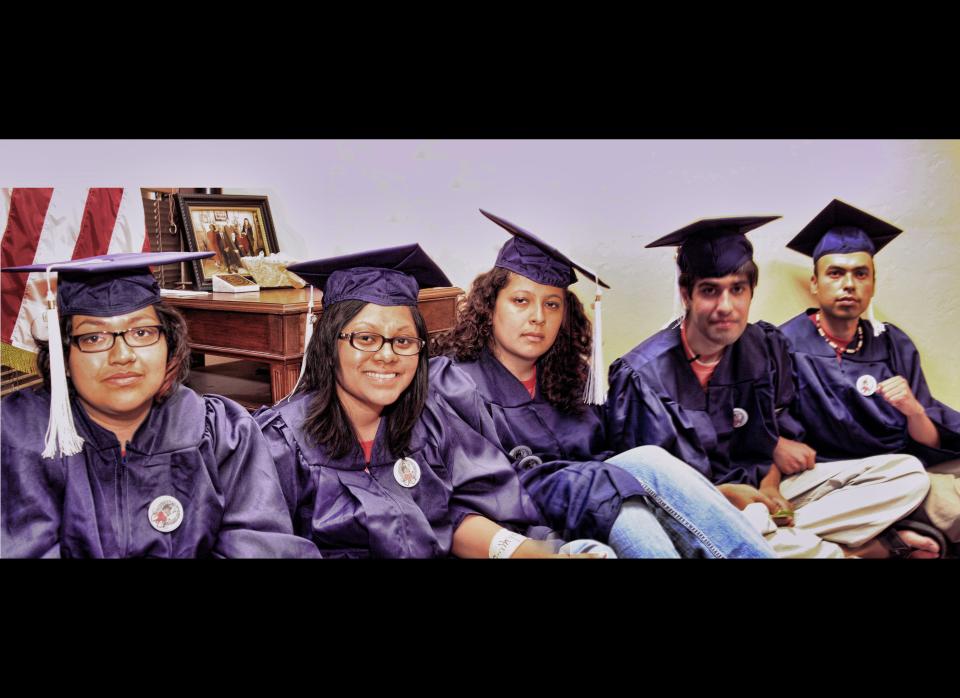

Photograph: Undocumented and Unafraid

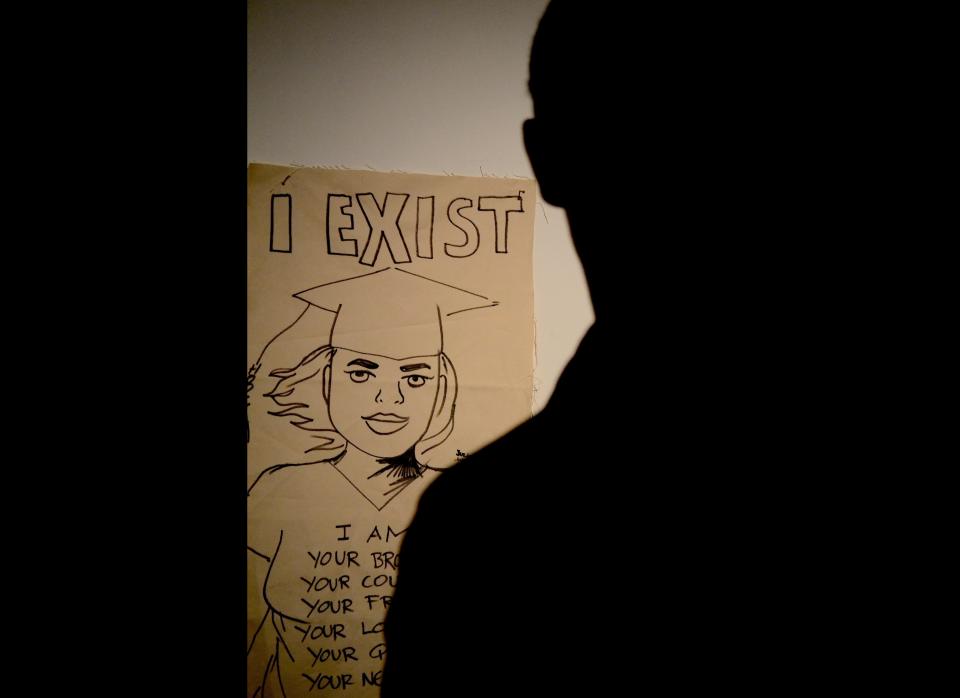

Photograph: "I Am Undocumented"

Photograph: Students sit inside Senator McCain's office

Photograph: "I Exist"

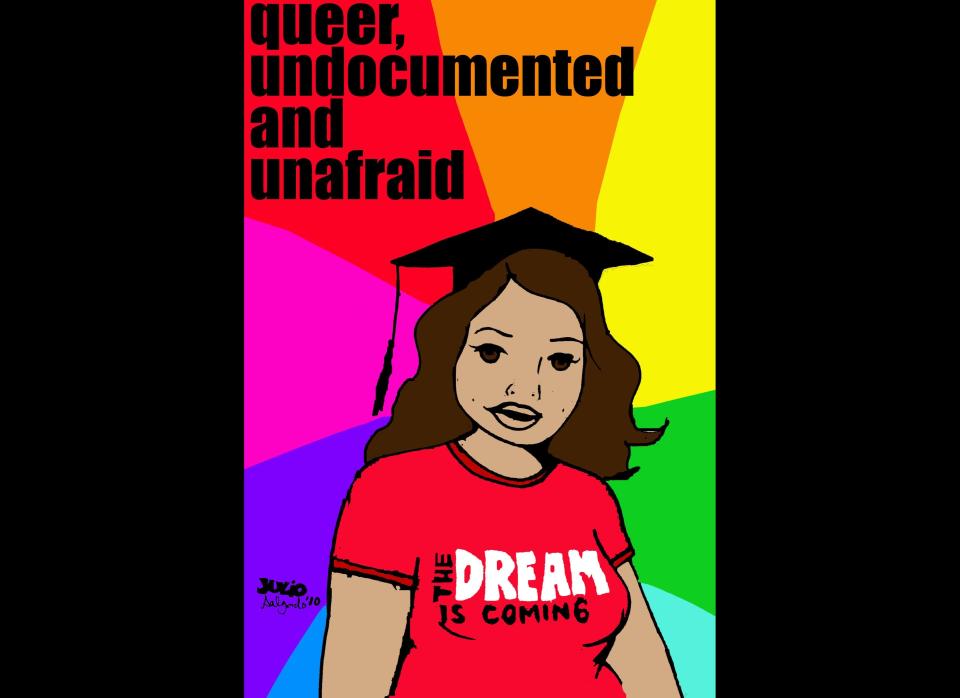

Illustration: Queer, Undocumented, and Unafraid

A Standing Room Only Crowd Celebrate the Book's Launch

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.