Why Britain’s mental health crisis threatens to doom a new generation

Psychiatrists speak in the most dramatic terms when describing the explosion in demand for mental health services among young people.

“It is horrendous and incredible,” says Dr Lade Smith. Depression, anxiety and eating disorders have all seen a “massive increase”, she says. “It has gone up enormously, particularly over the past three or four years since the pandemic.”

Britain as a whole is in the grip of a mental health crisis that has reached such a scale that it is now having an economic impact. Ministers have made tackling the problem – and helping people back to work – a priority.

Yet the worrying prevalence of mental health issues among young people suggests the problem is deep-seated and could leave long-lasting economic scars.

“If you don’t treat the child, that child does not complete their GCSEs. If they don’t finish school, they don’t go to university,” says Smith. “If they don’t go to university, they are less likely to get a job that pays the kind of wages that puts loads of money into the tax coffers.”

Experts such as Smith believe more support is needed in schools to tackle the problem before children drop out of education.

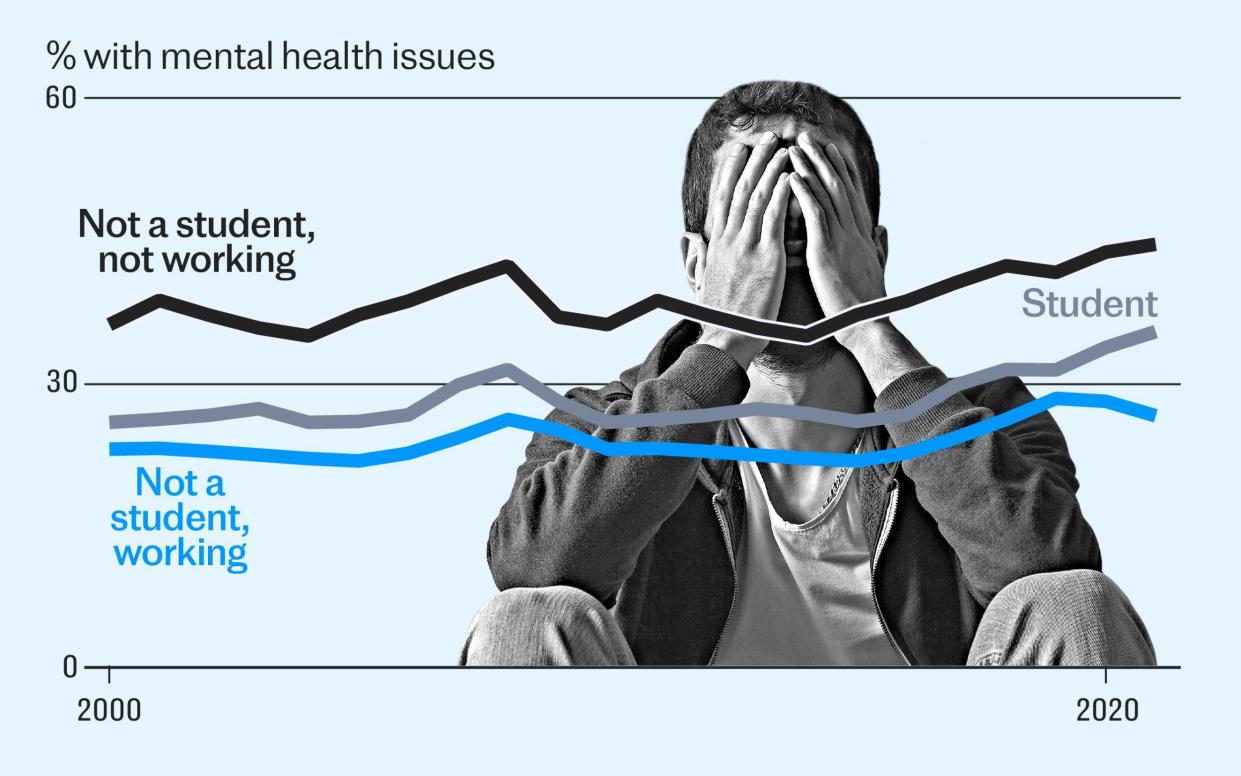

The pandemic has fuelled the child mental health crisis but the problem did not start there.

“For the past 10 or 15 years, we have had an increase in the percentage of people requiring mental health support,” says Smith, who focuses on treating young adults.

The reasons are complicated and manifold, she says, but include the long economic impact of the financial crisis, which put families under strain, as well as the crippling effects of the pandemic and lockdown, which increased loneliness and isolation.

She also cites expensive and insecure housing as a factor, as well as the potential for social media to feed users a cycle of negative posts.

Treating so many people is tough and there are not enough doctors to meet the need. Almost one-fifth of consultant posts are vacant in the specialism, says Smith, who is also president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

NHS numbers tell a similar story. Last year 1.2 million people were on the waiting list for community mental health services.

More than a quarter of a million children and young people referred to mental health services in 2022-23 were still waiting for support at the end of that period, the Children’s Commissioner for England has found.

This is not merely a crisis for the individual patients or for the health service as a whole. Poor mental health is now so widespread that it is becoming a drag on the economy.

“The number of young people not working due to poor health has doubled in the last decade. People in their early 20s are now more likely than those in their early 40s to be out of work due to poor health. That is really quite striking,” says Louise Murphy, economist at the Resolution Foundation.

“It is very different to what we saw 25 years ago, when there was a very straightforward trend that the older you got, the more likely you were to have poor health and therefore the more likely you were to be out of work.”

Worsening mental health is a key factor behind this trend.

Missing out on the early stages of a career can have lifelong effects on earning power, known to economists as “scarring”. In effect, people never catch up after missing out on these crucial early opportunities.

Policymakers are worried and searching for solutions. However, at the moment it looks as if the situation is only likely to get worse.

A growing number of school children are suffering with mental health conditions, meaning that unless something changes dramatically a new generation of youngsters are likely to struggle when they leave education and – if they are well enough – seek work.

More than one in five pupils aged between eight and 16 are believed to have a “probable mental health disorder”, according to NHS surveys. That is up from one in eight before the pandemic.

On top of that an additional 12pc are deemed to have a “possible disorder”.

The figure rises to nearly a quarter among older teenagers, aged from 17 to 19. In this group, almost one in three young women are thought to have a probable disorder.

Half of mental illnesses start before the age of 14, says Smith, with 75pc beginning by the age of 24. Early treatment can cure around one-quarter of cases completely. Waiting risks leaving sufferers with chronic conditions and relapses.

Tackling this mental health crisis – and the associated worklessness that goes with it – has become a priority for the Government.

Employers are desperately short of staff – there were more than 900,000 open vacancies at the start of the year, according to the Office for National Statistics. Doing more to hire and keep those with mental health conditions in work would be good for the workers and good for the companies.

Mel Stride, the Work and Pensions Secretary, last month unveiled plans to make 150,000 people signed off with mild mental health conditions look for work.

“As a culture, we seem to have forgotten that work is good for mental health,” he said, in remarks which attracted some criticism.

“While I’m grateful for today’s much more open approach to mental health, there is a danger that this has gone too far. There is a real risk now that we are labelling the normal ups and downs of human life as medical conditions which then actually serve to hold people back and, ultimately, drive up the benefit bill.”

The Government has announced multiple schemes aimed at helping people suffering from mental health conditions into work.

Tony Wilson, director of the Institute for Employment Studies, says some initiatives, such as the Individual Placement and Support in Primary Care Initiative, have yielded good results.

The scheme sends employment advisers to help patients in hospital with job applications alongside their normal treatment, with the aim of breaking the cycle of poor mental health and worklessness.

“The integration of employment advice with mental health talking therapies and mental health support is really important,” says Wilson. “It is achieving really significant impacts, and those impacts bring real benefits to individuals and the Exchequer, as the alternative would usually be people staying off work for a very long time.”

The scheme requires both the Department for Work and Pensions and the Department for Health to work together.

Smith believes collaboration such as this is key to tackling the mental health crisis among young people. The NHS must work with the education system to help identify and treat problems early.

More specialist support in schools is key, says Smith. Assessing pupils in situ allows “short, sharp treatment [so they can] get better and get back on with their lives”.

Murphy’s research found four in five 18 to 24-year-olds who are out of work because of ill health have no qualification beyond GCSEs.

The situation can become self-reinforcing. No work means no extra experience or on-the-job training, making it harder to get on the career ladder. No work breeds isolation and can be bad for mental health.

“Work is good for your health,” Smith says, “as long as it is meaningful, useful, you know what your role is, and you can be productive.”

Financially, it also helps fund a better lifestyle that can improve your health: paying for gym membership, say, or relaxing holidays.

Smith says: “If you want UK Plc to be successful, you have to have children who become adolescents who become functioning adults.”

A government spokesman said its £2.5bn Back to Work Plan was helping people with mental health conditions “break down barriers to work and put an additional 384,000 people through NHS Talking Therapies”.

They added that the Government was “continuing to roll out mental health support teams in schools and colleges, investing £8m in 24 early support hubs and expanding talking therapies services”.