Why Australia keeps an arm’s length from South China Sea tensions, even as it draws closer with the Philippines

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. addressed the Australian Parliament last week there was no mistaking the fighting talk.

The Philippines was on the “front line” of a battle for regional peace, he said, battling “actions that undermine regional peace, erode regional stability, and threaten regional success.”

He likened the situation to 1942, saying his country would be “firm in defending our sovereignty, our sovereign rights, our jurisdiction,” and would “not allow any attempt by any foreign power to take even one square inch of our sovereign territory.”

Neither was there any doubt about the intended target of his words, even if he didn’t mention it by name: this was all about China.

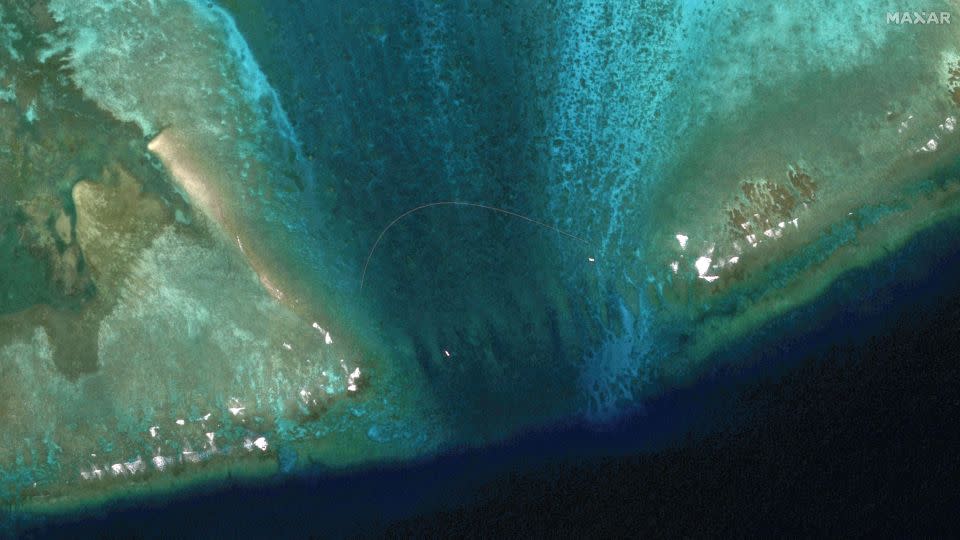

Beijing’s actions in the South China Sea, where it has numerous territorial disputes with Manila, have become increasingly aggressive since Marcos won the presidency a little less than two years ago and took over from his more China-friendly predecessor Rodrigo Duterte.

Since then, according to Manila, China’s coast guard has regularly harassed Philippine fishing vessels in the fertile waters near Scarborough Shoal – most recently on February 22 – and fired water cannon on Philippine ships resupplying a military outpost in the Second Thomas Shoal.

Amid these increasingly aggressive maneuvers, Marcos has made little secret of his aim to shore up allies against China, and for good reason; this is a David-and-Goliath-style contest. Manila’s navy is undermanned, underfunded and underequipped, while China’s is the largest in the world - even without counting the “little blue men” militia various nations accuse China of using to push its territorial claims.

Luckily for Marcos, the expansiveness of China’s ambitions – it insists almost all of the resource-rich 1.3 million square miles of the sea are its sovereign territory, despite a 2016 ruling to the contrary by an international tribunal in the Hague – means he has plenty of potentially sympathetic ears.

Chief among those is the United States, which, since Marcos came to power, has been steadily firming up a relationship that suffered during the Duterte years with deals that expand its access to Philippine military bases.

Marcos’ fiery speech to the Australian lawmakers shows he also sees Canberra as a potential ally in the South China Sea dispute, and he is widely expected to push the issue at a special summit between Australia and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in Melbourne on Monday. That meeting will also be attended by several other nations with territorial disagreements with China – including Vietnam, Brunei and Malaysia.

But most experts say Canberra is likely to be wary about wading into what is a third-rail issue for China – Australia’s biggest trading partner – given its own relationship with Beijing is still recovering from the punishing trade restrictions China slapped on Australian exports in 2020 after then-Prime Minister Scott Morrison called for an independent inquiry into the origin of Covid-19.

Collin Koh, research fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, said Australia was unlikely to back any tough language at the summit pertaining to the South China Sea or any other hot-button issue.

He said that while Australia wanted to use the event to position itself as a credible regional partner for political, security and economic cooperation, it would be keen not to be forced into the binary competition between China and the US.

At the ASEAN meeting on Monday, Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong annouced Canberra would be investing $41.7 million (64 million Australian dollars) in programs with ASEAN partners over the next fours years.

The money will be used to “expand Australia’s maritime cooperation with regional partners and contribute to the security and prosperity of the region,” a statement from Wong’s office said.

Partners, to a degree

Meanwhile, Marcos’ visit to Australia has notched up some notable successes. The two countries signed three memorandums of understanding, including an agreement to boost collaboration on maritime security by “promoting respect for international law,” and other agreements on cyber, critical technology and competition law.

“Our cooperation is an assertion of our national interest and a recognition of our regional responsibility,” said Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese.

Those agreements built on what was already a blossoming relationship, with Manila and Canberra having elevated their bilateral ties from a comprehensive partnership to a strategic partnership when Albanese visited Manila in September last year – in what was the first visit by an Australian prime minister to the archipelagic nation in 20 years.

But experts say the developing partnership is more driven by economics and deals to boost tourism and technical exchanges than it is military links. While in November, they conducted their first joint sea and air patrols – and did so in the South China Sea – analysts point out Australia still has no direct security commitment to the Philippines if a crisis were to break out in the disputed waterway.

The United States, meanwhile, has a mutual defense treaty with the Philippines in a relationship that dates back to the aftermath of World War Two.

Why is Australia holding back?

Although Australia is one of ASEAN’s most highly valued partners, it would not want to be seen as “too forward leaning” in supporting regional militaries while it was still mending its relationship with China, said Susannah Patton, director of the Southeast Asia Program at the Lowy Institute.

“Australia is not a small player, but it’s also not a decisive influence,” Patton said of Canberra’s role in Southeast Asia, adding that it would be cautious about being dragged into any maritime security flashpoints.

Other experts say that while Australia is not as vocal as the US in calling out China’s aggressions, Canberra is still hedging against Beijing’s growing military presence in the region by actively fortifying its regional security alliances.

Australia’s foremost military priority remains with the Quad, which also includes the United States, Japan, and India – a grouping whose mantra is a “free and open Indo-Pacific,” and which Beijing views as an “exclusionary bloc” that undermines China’s interests.

Under another pact, AUKUS, the US and the UK have agreed to help Australia build and maintain nuclear-powered submarines by the early 2040s, in another alliance that has angered Beijing. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman Wang Wenbin said the trilateral pact would “only exacerbate the arms race, undermine the international nuclear non-proliferation regime and hurt regional peace and stability.”

Given it is already part of two security pacts that have raised Beijing’s hackles, Australia might decide it’s wise not to further anger its trading partner by siding too heavily with the Philippines in the South China Sea, some experts say.

Nick Bisley, dean and professor at La Trobe University in Melbourne, said the Australian view of foreign policy remained “overly anxious about China” and that was why Canberra was so particular in the wording of any of its military commitments in contested zones.

As Bisley put it, “We don’t like what China does, but we’re not going to put ourselves in harm’s way.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com