Why are Americans drugging themselves to death?

Americans are fond of calling the United States the greatest country in the world. But that doesn't mean the sentiment is universally shared. Critics point to various measures that raise doubts about the judgment: high rates of childhood poverty, sky-high levels of gun violence, a health-care system that covers fewer people at greater per capita cost than any other country in the world.

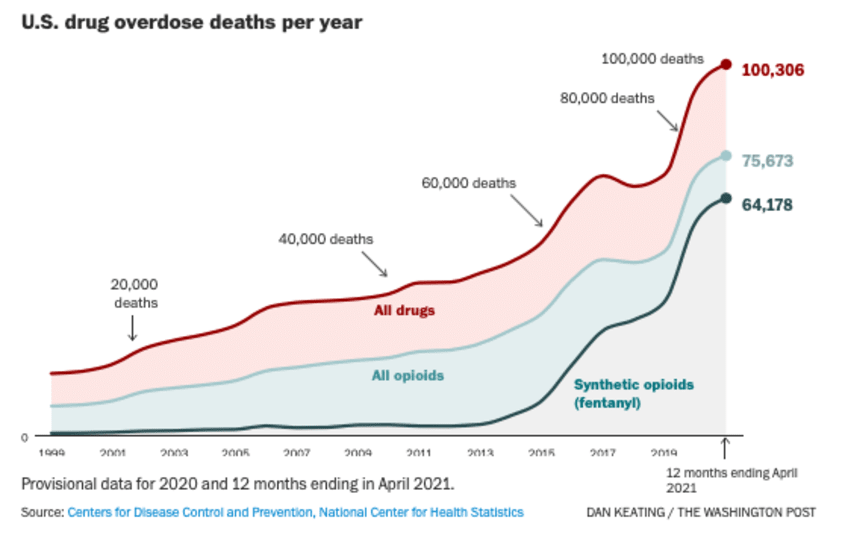

But perhaps the most shocking statistic of all is how many Americans have been dying of drug overdoses in recent years. As recently as 20 years ago, roughly 20,000 Americans a year were dying of drug abuse. By 2011, the number had doubled. It had doubled again, to 80,000, by 2019. And now, the government has released figures showing that during the 12-month period ending in April 2021, more than 100,000 Americans died from overdoses.

The Washington Post

A five-fold increase in two decades is an astonishing statistic. Why is it happening?

The immediate reaction online to this grim record, especially on the right, focused on the pandemic, and above all government-enforced lockdowns, as the culprit. Shut down the economy, tell people to stay in their homes with few opportunities for social interaction for months on end, and many will float away into a depressive, drug-induced oblivion that sometimes ends in accidental or intentional death.

There's probably some truth to this: The pandemic has taken a significant psychological toll on many of us. But of course, drug deaths were rising sharply before the pandemic. Maybe we wouldn't have hit 100,000 deaths in a 12-month period until 2022 or 2023 without a public health emergency. But we most likely would have gotten there eventually — because something much bigger than the pandemic has been contributing to steady increases in drug overdose deaths.

This "something" is a form of spiritual agony.

We can get a sense of its nature in the kinds of drugs people are abusing. The overwhelming majority are opioids, with the synthetic opioid Fentanyl now by far the most common. These drugs are popularly known as painkillers — substances that alleviate distress and induce euphoria. A lot of Americans crave relief from various forms of unhappiness, discontent, malaise, agitation, and other emotional and/or physical pain.

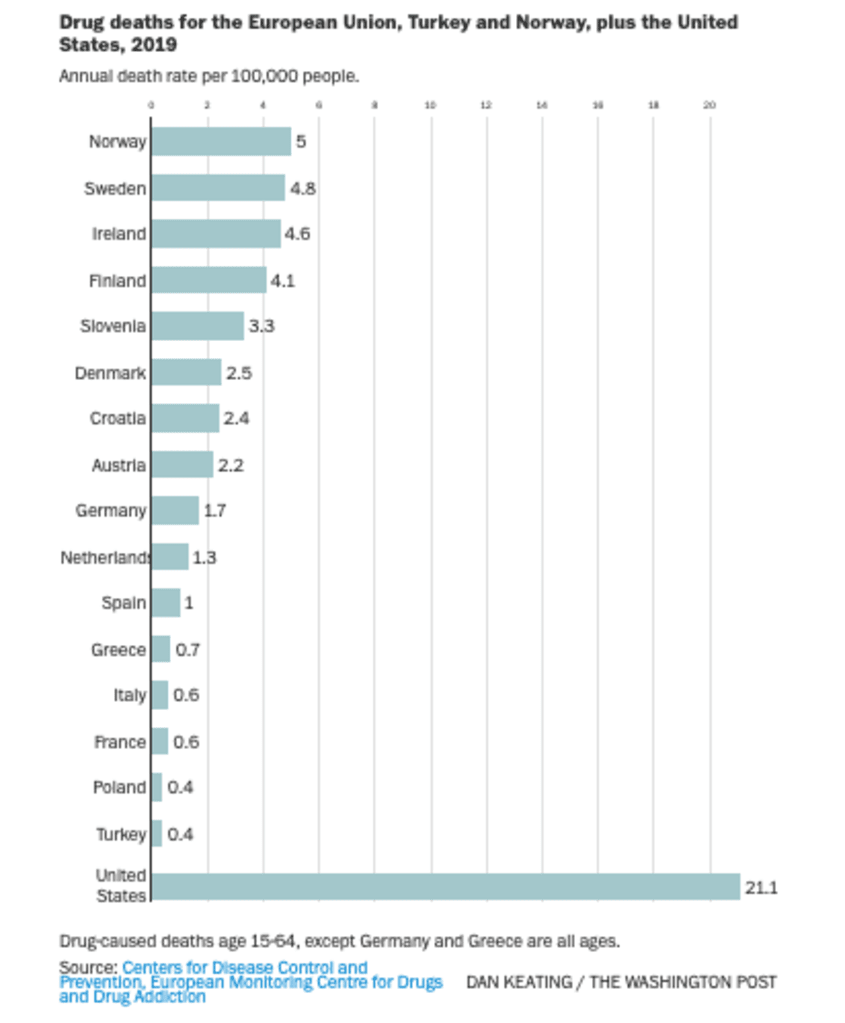

And this problem is uniquely acute in the United States. In The Washington Post's story about the spike in overdose deaths, the most alarming chart by far is one comparing annual overdose rates in the U.S. to those in the wealthy countries of the European Union, plus Norway and Turkey. (The data comes from 2019.) Poland and Turkey have the lowest rates, at 0.4 deaths per 100,000, with Norway coming in at the second highest rate, at 5 deaths per 100,000. And then there's the U.S. at the bottom of the chart, the undisputed leader, with a bar stretching more than four times the length of Norway's — to 21.1 deaths per 100,000 overdoses.

The Washington Post

Now add in the results of a 2015 study showing that 32 million Americans (one out of every seven adults) struggled with a serious alcohol problem during the previous year — and that nearly a third of all Americans will exhibit signs of an alcohol-use disorder at some point in their lives. And there's the fact that the United States leads the world in per capita consumption of prescription medications for anxiety and depression, with roughly 13.2 percent of adults using them before the pandemic contributed to a major use spike.

Put it all together and the picture is clear: Many Americans are struggling mightily with profound unhappiness that drives them to seek refuge in various forms of prescribed or self-administered chemical medications, some of them potentially life-threatening.

But the question of "why" remains.

I've used the word "spiritual" to describe this crisis because it seems to involve such comprehensive issues, many of them wrapped up with existential questions of elemental happiness. Our country's civil religion tells us America is the greatest nation in the world because we're left free to pursue happiness however we wish. But who among us really knows how to be happy? Some are raised in traditions that cultivate tacit knowledge of how to flourish and thrive by providing individuals with fixed purposes they are expected to pursue throughout their lives. But many of the rest of us find ourselves flung into the world without such guidance, unsure of what might fulfill us.

At the same time, our country's networks of sociality have become attenuated in recent decades. Rates of church attendance and religious identification are in a state of free fall. Other communal institutions, including marriage and family but also extending to clubs, unions, and fraternal organizations, have been declining for decades as well. Perhaps most alarming of all, recent studies have shown that people are making fewer friends, with unprecedented numbers claiming to be entirely friendless. No doubt this has gotten worse as the result of the enforced isolation of the pandemic.

It's hard to think of a more effective recipe for loneliness, depression, and drug addiction than this. It might also be an ideal breeding ground for radically illiberal politics of the far left and right, especially when it's combined with the ersatz connection people seek and find online in politically siloed social-media networks.

Either way, Americans appear to be losing their way in the world, anxiously pursuing a happiness that eludes them, and ending up drawn to toxic chemical and ideological substitutes for relief from the misery of a disconnected, purposeless existence.

Which might just be another way of saying that radical individualism is hard — and quite possibly a burden too heavy for many of us to bear. That doesn't mean it will do any good to pine for an easy path to redemption from our struggles and the return of a past in which communal contentment was more commonplace. But it might mean it would be a good idea to begin doing the arduous work of laying a foundation for such a rebirth by cultivating habits and pursuing social projects that could issue in new forms of solidarity — schools, sporting events, religious enterprises, forms of collective artistic expression.

That certainly won't be easy, and it may not succeed. But the alternative — an ever-increasing malaise and ever-deeper withdrawal into isolation, psychic suffering, and often lethal self-medication — is bound to be worse.

You may also like

The Democrats need a unified adversary in 2022

A Harry Potter reunion is happening, reportedly without J.K. Rowling

Report: House to vote Wednesday on censuring GOP Rep. Paul Gosar over video