Whitney Westerfield is leaving Frankfort. Why? He’s changed, but his party’s changed more

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On Feb. 8, state Sen. Whitney Westerfield drove to the Chamber of Commerce dinner in Lexington.

He did not want to go.

He’d had a terrible day, a “genuinely crappy day,” where he watched some of the changes he’d made in Kentucky’s juvenile justice system begin to be unraveled by his colleagues. Criminal justice reform was about to be decimated by House Bill 5, and Donald Trump was once again about to become the GOP nominee for president.

But then, as the Fruit Hill Republican made his way to his table at the back of the room with all the other people filtering in, people started stopping him to shake his hand. “They kept thanking me for what I was doing,” Westerfield said last week.

“I lost count of these people that I had never met, but they knew who I was.

“That’s how that genuinely crappy day ended, and it felt great because I felt I’m not out here all alone. I’m not the only one who feels this way. I’m not patting myself on the back, it was just nice to know there were other people who feel the same way.”

Whitney H. Westerfield, 43, is getting ready to leave the place where he has served for 12 years, and even in leaving, he feels very alone.

He’s changed, his party has changed, Frankfort has changed, and frankly the three things just aren’t syncing that well these days. The young county prosecutor from Hopkinsville who once saw everything in black and white views the full color spectrum these days.

A year ago, he announced his retirement because he just couldn’t keep spending so much time away from his wife, Amanda, and their two children, Hadley, 9, and Hayes, 6. As the General Assembly started in January, he had three more reasons: Amanda was pregnant with triplets. He could go home, devote himself to his law practice and be a more present father.

But also lurking was the fact that his job in Frankfort wasn’t much fun any more, and he simply wasn’t getting as much done.

The Senate GOP didn’t have as much space for an evangelical Christian-anti-abortion hardliner who thought a government that banned abortion needed to pay more attention to helping families and children. They didn’t want to listen to him preach about how putting more people in jail would not lower crime rates. They didn’t support his attempts to keep guns out of the hands of the mentally ill.

And they do not like to see him pillory Trump and his ilk on a frequent basis on X (formerly Twitter), like he did when Trump started hawking Trump Bibles during Easter.

“Just gross,” Westerfield wrote.

When Trump mouthpiece Charlie Kirk said compassion for migrants was a moral failing, Westerfield responded on X: “Believers — particularly those with broader reach — need to refute and rebuke these awful, un-Christlike, unscriptural, racist, bigoted garbage takes.”

“I get called a RINO (Republican In Name Only) 17 times a day,” he said. “I’m the same conservative Republican I’ve always been. I’m not sure why people don’t see that.”

Westerfield has taken a long journey to cement his political persona, only to find political solitude.

The question for Kentucky and for the rest of the country is one Liz Cheney fans must be asking right now: Is there even room for the tiny handful of Republicans who oppose Trumpian orthodoxy in Republican circles? Or do they end up like Cheney, the ousted and vocal anti-Trump U .S. House member from Wyoming, and now Westerfield, alone and out of office and irrelevant to the politics of the day?

‘We don’t always agree’

March 15 was something like Feb. 8, only in reverse order.

With his wife and two kids standing at his desk, Senate Majority Leader Damon Thayer introduced the resolution to honor Westerfield and his work. Senator after senator rose to praise him, using words like “wonderful, tremendous, integrity, courage, convictions.”

A lot of them started with “...While we don’t always agree on the issues,” then on to what a wonderful person he is.

Later that afternoon, Westerfield withdrew the five amendments he’d made to House Bill 5, the draconian crime bill that would criminalize homelessness, put many more people in jail and cost $1 billion. He didn’t have the votes, and despite the fact that he’s the longtime chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, he had not been included in the work group that had crafted the bill over the past year.

So, he decided to use his lame duck privileges to burn some bridges.

“This is a serious mistake,” he said on the Senate floor.

“This bill falls in to the category of legislation that really has everything going for it but not in a good way. It’s got all the kinds of momentum, it’s got lots of support, it’d be the easiest vote most of you would take.”

But, Westerfield said, it will cost money that Kentucky doesn’t have and it won’t fix problems the way it should.

“Some of those groups that have confided in me — they hate this, and they don’t know how they’ll afford this, but they don’t want to speak up because we haven’t passed a budget yet ... and they don’t want to make us mad,” he continued.

“I hate to point out the obvious, but some of us up here operate like that. Hold grudges and are spiteful. I resent all of them in both parties that behave that way. There are people not speaking on this bill — I am not naming them because there are people who are spiteful and hold grudges.”

It passed 27-9, almost entirely along party lines except for the no votes of Sen. Adrienne Southworth, R-Lawrenceburg, and Westerfield.

The words of a lame duck senator, no doubt, but it’s not entirely clear he wouldn’t have said them anyway. This session has been a series of grudges, held by him and fellow lawmakers.

He worked the entire year on the Crisis Aversion and Rights Retention act, a thoughtful attempt to stop gun violence by people with mental illness in the wake of the Old National Bank shooting in Louisville a year ago.

It was supported by some law enforcement, but not many fellow Republicans. It never even got a committee vote.

Senate Bill 34, which would have widened the safety net for low-income families, died in Appropriations and Revenue. He co-sponsored a bill to abolish the death penalty, which died on the vine.

For the second year in a row, he sponsored the CROWN Act legislation, which banned discrimination against natural hair styles in schools and at work. It was assigned to committee and never heard, despite, as he says, a lot of fruitless, impassioned argument in caucus. Same with a bill to abolish slavery out of our constitution.

These are all deeply personal to him, and their total dismissal by his colleagues clearly irks him.

“I’m here for policy,” he said.

“The politics are part of it — members right now casting votes because they’re in a tough primary. I know that factors in, but at best that’s a secondary concern. So when I get kicked in the teeth of policy because of politics, I don’t like it.”

A religious zealot?

Gerald Neal has been a state senator since 1989. He’s watched a lot of fresh-faced Mr. Smiths come to Frankfort from rural Kentucky with firm ideas about crime and punishment, right and wrong. He’d watched Westerfield’s unsuccessful runs for attorney general and the state Supreme Court, and at first he figured Westerfield was pretty much the same as those he’d seen before.

“I perceived him as a religious zealot, the way he wore his religion on his sleeve,” Neal said. Then, as time went on, he thought: “Am I watching a transformation, or am I watching a person not being strategic, free to say exactly what he thinks?”

But he was always very consistent, and at the end of the day, it was consistent with what he was saying about religion, too. “Maybe I didn’t understand he was more complex than just a label,” Neal said.

Westerfield is not a moderate. He mostly votes with his party, and their candidates, with the notable exception of Trump, and he opposes abortion to such a degree that he won’t consider exceptions for rape and incest.

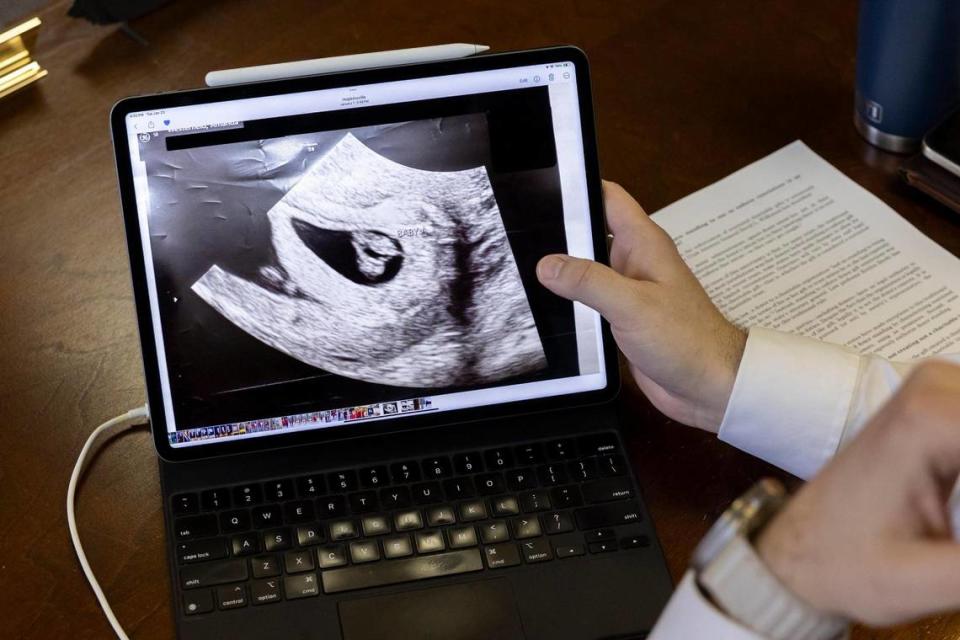

But Neal was right about a been a transformation, too, one that really began nine years ago, when the Westerfields adopted a little girl named Hadley. A few years later, they adopted an embryo through an agency, which Amanda Westerfield carried to term. Hayes is now 6.

Both children are bi-racial, and that fact upended the perspective of a largely white life in rural Christian County.

“When Hayes was little, like 2 or 3, we got one of those big train sets,” Westerfield said. “I remember putting it together, and there were all these figures with it and they were all white. That never would have occurred to me when I first got this job. Now that’s not a policy thing, but it screams at you when your children are surrounded by it.”

The Westerfields adopted two more embryos, which turned into the triplets that Amanda Westerfield is now carrying. That’s in part why, in the wake of the Alabama Supreme Court decision, Westerfield wrote legislation to limit the liability of facilities that do IVF.

It didn’t get out the of Senate Health Services Committee.

His children, too, prompted his work on the crisis aversion legislation that would have been a first step to preventing mentally ill people from getting guns.

“The Uvalde shooting, which was just as dreadful and tragic as every other school shooting or mass shooting we’ve seen in Kentucky and outside of Kentucky,” he said.

“But on that day 2022 all I could think about was my kids making the phone calls those kids were making. And I thought why aren’t we willing to have a conversation about it? I don’t know what it needs to look like yet. I don’t know what the best solution is. And I’m open to hearing and I’ve said this to every opponent of CARR. You tell me what you think we should do? What’s your solution?”

They don’t have a solution because it would have to be outside the lockstep of modern gun politics, despite overwhelming public support for change. As former Republican Secretary of State Trey Grayson said about the issue: “He’s been a real advocate for criminal justice reform but the pendulum has swung the other way on that one.”

“I feel like I feel like I’m a much better person having the perspective that I have now than I did 12 years ago but the party is not, and it’s starting to have more of a presence here in Frankfort,” Westerfield said. “It’s become a lot about culture war stuff and battles every day.”

He assumes the culture war on “wokeness,” and not just ignorance and racism, is why his colleagues have defeated the CROWN Act two years in a row.

The CROWN Act, which stands for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair, stemmed from a national movement started in 2019 to extend statutory protection to end discrimination against mostly Black women, but plenty of other people, too, because of their natural hair and race-based hairstyles such as such as braids, locks, twists and knots in the workplace and public schools.

According to the national coalition, more than 20% of Black women between the ages of 25 and 34 have been sent home from work because of their hair.

Last year, Westerfield said he hoped to educate his caucus about the issue so that it would pass this year. This year, it didn’t get out committee.

Regrets, I’ve had a few

Changing perspectives mean Westerfield has some regrets. He regrets it took him so long to see the perspective of medical marijuana advocates. He regrets voting yes on Senate Bill 150 last year.

He regrets having advocated for Dayton Jones, a convicted sex offender whose sentence was commuted by Gov. Matt Bevin in December 2019, without having spoken to the victim.

“I regret being a coward when I shouldn’t have been, and not giving people grace when I know I needed to,” he said.

He regrets that these days it seems impossible for people of conscience to stay in politics.

“I guess it is possible but they have to compromise, they have to make sacrifices I’m not willing to make today,” he said. “I aspire to higher office, but I’m probably unelectable in a primary anyway.”

Westerfield has already run for Kentucky Attorney General, losing narrowly to Gov. Andy Beshear, and the state Supreme Court, but both those jobs would be appealing to him.

Still, is there room in politics for the Whitney Westerfields of the world? He would say no.

His colleague, Sen. Julie Raque Adams, R-Louisville, has also worked on issues that help children and families, albeit in a less confrontational way.

“If you look at the makeup of my district, the fastest growing segment is independents, so I think that while we all have to pick our jerseys, that’s not to say you can’t take into consideration people who are becoming of voting age, and don’t like either party,” she said. “So yes, I think there is a place.

“I think he truly does have a servant’s heart, and I think he will have his hands full with five babies, but my prediction is you’ll see him pop back up again.”

Secretary of State Michael Adams — who has refuted Trump’s election denial and won the most votes of any constitutional officer in the 2023 election — says he believes the the real divide in the party is between those who want to govern and those who don’t.

“Whitney is a very practical, data-based kind of guy,” he said. “Other people don’t want to know. They just want to put their fingers in their ears and say what they want to believe. It’s a lonely thing to be a fact-based person, you’re kind of on an island.”

But for the sake of Frankfort and our democracy in general, Westerfield said he hopes that facts will make a comeback in our misinformation-drenched world.

“HB 5 is a recent example — a bunch of legislators will go home and say they were tough on crime,” he said.

“No one will ask about the price tag, none of the constituents will have read the bill or know what we’re criminalizing. They don’t have to say what crime rates actually are, and no one is going to tell constituents that what you’re hearing on Fox and Newsmax isn’t reality.”

“We can always start fresh. We can keep digging the hole or we can stop digging,” he said. “The hole is deep, but the first thing to do is put the shovel down.”