Where did Black travelers stop in Stark years ago? New Cleveland Green Book revisits spots

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

CANTON − Green Book Cleveland, a new restorative history project of Cleveland State University and Cuyahoga Valley National Park, retells the story of how Black travelers relied on the once-popular travel guide.

The project features interactive maps showcasing locations of businesses and venues throughout Northeast Ohio where Black visitors were welcome, including spots in Stark and Summit counties.

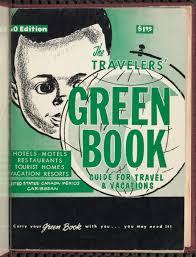

From 1936 to 1966, Victor Hugo Green, a Black travel writer from New York City, published the "Negro Motorists' Guide," later known as "The Green Book" for other Black travelers to advise them where they could safely eat, sleep and even get gasoline.

During the early half of the 20th century, public accommodations such as hotels, restaurants and night clubs often refused to serve Black customers. Even in Northern communities, which didn't openly display "whites only" signage, there was an unspoken understanding that Black visitors weren't welcome in certain establishments.

According to its website, the latest project originated with a student research effort led by Cleveland State University associate history professor Mark Souther. It is one of the pilot projects for the PlacePress plugin developed by Erin Bell in the Center for Public History + Digital Humanities under a Digital Humanities Advancement Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

A permanent place: 'Museum within a museum.' Black history to be highlighted in exhibits at McKinley library

What Stark County sites are highlights in Green Book Cleveland?

Green Book Cleveland's interactive website includes places that were published in some of the original guides, and the stories behind them.

They include a home at 1104 Sixth Street SW in Canton that offered lodging. The house — which still stands — is listed as a "tourist home" belonging to Mrs. K.S. Sommerville between 1939 and 1940. Another name, K. Willis, also has been found but the connection is unclear.

There's also an entry describing an early visit to Meyers Lake in 1899 by the Cleveland L’Ouverture Rifles, which brought 500 of its members to meet then-Ohio Gov. William McKinley. During their visit with McKinley, the Black delegation held an informal parade in downtown Canton, then took streetcars to Meyers Lake.

The website also makes mention of the Phillis Wheatley Association House at 612 Market Ave. S. In the 1930s, it was a welcome sight for single young Black women in need of a place to stay.

Named after a former slave who became America's first Black published female author, Phillis Wheatley Association housing still can be found across the U.S.

In recent years, the house served as offices for the MB Oil and Gas Co.

The website also lists the Clearview Golf Club in Osnaburg Township. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, Clearview was the first golf course in America designed and built by a Black man, the late William J. Powell of Minerva, in 1946.

While working as a security guard at Timken, Powell pursued a long-held dream of building his own course.

With financing from his brother and two doctors, he bought a 78-acre dairy farm. After his shift at Timken was over, he worked building a course on the farm.

It took him two years, but Powell opened Clearview Golf Club in 1948.

Powell called it “America’s Course,” and it was open to all.

In 1996, Powell was inducted in the National Black Golf Hall of Fame. The next year, he received an honorary PGA membership.

The course remains open today and is managed by Powell’s children, Larry Powell and Renee Powell.

Renee Powell is a professional golfer who played on the LPGA Tour. She is now the head professional at Clearview.

Alliance, Canton and Massillon locations showcased in Cleveland Green Book

Also included is Hunter's Restaurant at 527 Cherry Ave. SE in Canton from 1939-41 and in 1947, and then at 224 E. College Ave. in Alliance between 1948 and 1950.

From the 1920s through the 1960s, Cherry Avenue SE was home to a plethora of Black-owned businesses, including nightclubs, a hotel, restaurants, lunch counters, skating rink, two pharmacies, newspaper, and medical offices.

During the 1970s, most of the neighborhood was demolished to make way for U.S. Route 30, the Cherry Avenue Overpass, which stretches from Third to 11 Streets SE, and industrial space.

A tourist home belonging to Mrs. H. Baber at 649 N. Liberty St. (N. Liberty Ave.) in Alliance also made the Green Book from 1939 to 1941.

In Massillon, the site highlights Oak Knoll Park, which hosted Black outings in the pre-World War II years, and Catherine's Beauty Shop on Lincoln Way East in 1940.

Researching Black history isn't easy

University of Akron history professor Greg Wilson said he learned of greenbookcleveland.org last summer while preparing to teach the first graduate seminar for the university’s new master’s degree program in applied history and public humanities.

The interdisciplinary program focuses on public history and prepares students for careers in humanities organizations, businesses, government or the nonprofit sector.

One of Wilson’s students, Rose Vance-Grom, is a fifth-generation Akronite from Firestone Park. But like many others, she said she, too, was unaware of much of the history she researched for greenbookcleveland.org. Most of her work focused on Akron’s Little Harlem and Brady Lake near Kent.

Trying to see a clear picture of history, she said, is not always easy. Researchers rely on the archives of larger newspapers, like the Beacon Journal, but sometimes find conflicting information in small, Black-owned publications like The Call & Post in Cleveland or the Pittsburgh Courier, both of which covered Akron’s Black community.

Brady Lake, for instance, hosted a lot of Black entertainers, Vance-Grom said.

“But it was hard to differentiate what was open to Black people” or if they just entertained white people, she said. “It was hard to nail down if it was segregated or not and how that worked.”

She ultimately concluded that Brady Lake appeared to welcome Black people, but not all of the time. A 1935 article in the Call & Post about a jazz concert noted that Brady Lake “will be turned over to our people … for the first time in three years.”

One of Vance-Grom’s favorite discoveries, she said, is a mural painted on the back of Dirty River Bicycle Works in Akron’s Northside.

Green Book Cleveland is seeking more information about any of the places listed on its website, and others which are not included. Send emails to info@greenbookcleveland.org.

This article originally appeared on The Repository: Cleveland State revisits Green Book sites in Northeast Ohio