‘Where we belong’: Bond forged in war brings Afghan commando's family to Pennsylvania

NEW CUMBERLAND, Pa. – A mix of apprehension, anticipation and exhaustion coursed through Matt Coburn’s 6-foot-1-inch frame as he made the 30-minute drive from his house to the Harrisburg airport.

He had his wife's SUV – his truck wouldn't have enough space – and he'd arranged to borrow two car seats. Waiting at the terminal, the retired Green Beret wondered if his Afghan friend would still recognize him with his new beard and without the military buzz cut.

The last time the two men had seen each other was in Kabul, more than a year earlier at Camp Commando, a U.S. military base dedicated to training the Afghan National Army’s most elite fighters. Coburn, 47, and Azizullah Azizyar, 33, worked side by side for months as top-ranking commanders in their respective militaries, bound by a mission to build up enough Afghan battalions to keep the Taliban at bay as the U.S. prepared to end its longest war.

Neither man ever imagined the two would be reunited in south-central Pennsylvania – or that their lives would become so inextricably linked after the chaotic U.S. exit from Afghanistan and the Taliban’s terrifying return to power.

Azizyar's Delta Air Lines flight descended into Harrisburg just before sunset on Oct. 14. On board, he couldn’t conjure an image of what this new town would look like – let alone what this new country had in store for him, his wife and their three children. The past nine weeks had been a blur of terror and escape, refugee camps and military bases, paperwork and screenings.

“This is the place where we're going to live. This is the place where we belong,” he told his wife, Roqia, and their children before their plane landed that day.

When he emerged from the gangway into the airport, the former Afghan special commando officer tried to use his limited English to ask for directions.

Then he heard his name. “Azizullah!” Coburn waved his arms to get his Afghan friend’s attention before getting close enough for a big bear hug.

'They would have killed me in front of my family'

When Kabul fell to the Taliban, Coburn was driving home from a family vacation – his first since retiring from the U.S. Army after 24 years of service. He had deployed six times to Afghanistan; he'd trained and befriended hundreds of Afghan soldiers in that time.

Now, his phone was lighting up with messages from Afghan friends pleading for help and fellow veterans sharing evacuation strategies.

“Initially, it was just guidance on survival,” Coburn said. One Afghan soldier sent him a message asking if he should stay at his post, even though Afghan President Ashraf Ghani had fled the country.

The government you were supposed to defend is gone, Coburn told him. "You need to go find your family and protect them."

Azizyar didn't need any prodding. He had joined the Afghan army at age 18 – five years into the U.S.-led war – and rocketed up through the ranks to become the command sergeant major overseeing nearly 20,000 Afghan Special Operations Forces. Those forces were routinely deployed to the worst Taliban havens – which made him a prime target for retribution.

Even before Taliban fighters entered Kabul, he was constantly worried his children would be abducted or he would be killed. He often traveled in an armored vehicle accompanied by bodyguards.

"I felt danger every moment in Afghanistan," he said.

When he learned that Ghani had abandoned Afghanistan, the father of three raced home and hid his camouflage uniform with its red-and-yellow Special Forces patch.

"People were reporting to the Taliban that I was working for the government and was quite important," he said. "If the Taliban found me, they would have killed me in front of my family."

He thought about what it might be like for his two boys, 4-year-old Rashid and 7-year-old Roheed, and his 5-year-old daughter, Zainab, to see him executed. Or worse, for the Taliban to kill his children as well.

The family fled Kabul for Jalalabad and went into hiding, until a friend messaged him to say that American veterans were working to get people out.

“My life is in danger … if you can help,” Azizyar wrote in a message to Coburn, sent through a friend who spoke better English.

By that point, Coburn was part of a frantic evacuation effort spearheaded by U.S. veterans, most of them former special forces like himself, through a group called Task Force Pineapple.

“I was sleeping 45 minutes a night, trying to help them move and hide,” Coburn said of the Azizyars and other Afghans who had reached out to him.

Azizyar sent copies of his family’s documents, then waited in a haze of sleeplessness and fear. He doesn’t even remember what day it was when he got the call to go to the airport. A neighbor agreed to drive them, and they rode with the lights on inside the car – hoping the Taliban would let them pass if they saw a woman in the vehicle.

The Taliban stopped them anyway and pulled Azizyar out of the car. As they searched him, he thought about all their documents tucked in Roqia’s clothes. He told them she was sick and needed a doctor. The militants let them go, and the family made it to the airport to join the desperate crowd.

Azizyar wore a red scarf to identify himself to Task Force Pineapple's contacts inside the airport; Roqia and the children were also wearing red.

It took 12 hours to get inside the airport.

He took a deep breath. "They're safe," he said to himself.

Survivor's guilt

The Azizyars arrived in Pennsylvania with few belongings, no money, and no work authorization permits. Azizullah does not speak English, though he understands a little. Roqia has not had any formal education.

Where Coburn and Azizyar once had interpreters to help them communicate about military strategy, they were now using Google Translate to navigate a purely civilian mission: renting a house, signing up for refugee assistance, finding an immigration lawyer, and getting the kids into elementary school.

“This whole thing has been so fast,” Coburn said as he recounted the frenetic days between the fall of Kabul and his friend's arrival. “Each step of the way, I feel like we’re blind people, walking around feeling the elephant.”

Coburn took medical leave from his job at Amazon after realizing the task of helping Azizyar's family resettle would essentially be full time. He was also emotionally and physically depleted, by both the evacuation effort and the "moral injury" of how the U.S. left Afghanistan – with little regard for the Afghan soldiers, particularly the special commandos, who had been bearing the brunt of the war for years.

"Knowing the risk that all of these Afghans are at is crushing me," Coburn said.

"You already have veterans that are suffering from post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety. Now you're adding in the idea that their friends may be killed, and you are helpless to do anything about it."

Since his arrival in the U.S., Azizyar's phone has also been buzzing with messages from those who didn't make it out. Even as he pivots to a new life, he's worried about his fellow soldiers. He's worried about his extended family. He's worried about the fate of his country.

"There's no work and no life," he said. "My colleagues and sergeants tell me that if there could be a way for them and other people (to escape), everyone might leave and no one would remain in the country."

Moving in, moving on

"Good morning! Good morning!"

Rashid, the Azizyars' bouncy, beaming 5-year-old, tries out his new English words as his parents pile their belongings onto two metal hotel carts: one small suitcase they brought with them from Afghanistan, along with boxes and bags gifts from Coburn and donations that have poured in since their arrival.

Coburn has been paying for the family to stay in a hotel in New Cumberland, a borough of about 7,000 people tucked alongside the Susquehanna River south of Harrisburg. Coburn lives nearby with his wife and teenage son in the neighboring borough of Mechanicsburg.

In the meantime, they've been working with the local chapter of Catholic Charities to find the family permanent housing. Their caseworker found a rental house with owners willing to take a risk on a new immigrant family with no credit history and no employment.

And today is moving day.

"The house is about 16 mins from Matt’s," says a smiling Azizyar. "I'll be close to my friend."

Before arriving here, the family spent 40 days at Fort Pickett in Virginia, where they had health screenings and other vetting measures.

Coburn had told Azizyar he could put his name and address down if he had nowhere else to go. A month later, the Catholic Charities caseworker called asking if he would be willing to sponsor the family. Coburn's response was an unequivocal yes.

"He's my brother," he says as they finish packing up the hotel room.

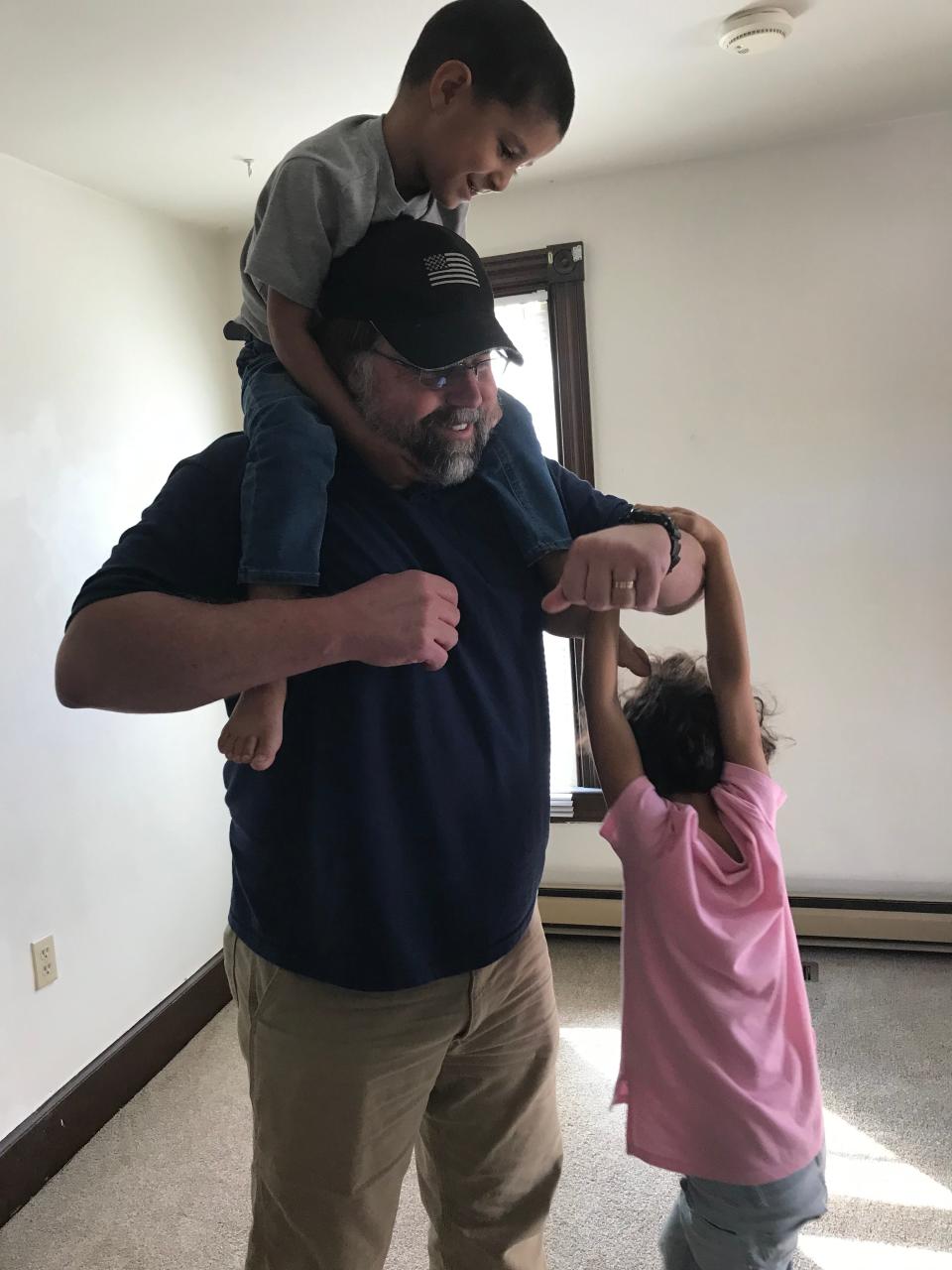

Rashid grabs Coburn's big forearm, and the former Green Beret swings him around. Zainab, her curly brown hair in a fountain ponytail, waits patiently for "Kaka Matt" – the Dari word for uncle – to give her a spin. Asked if she knows where they are going, Zainab names the village in Afghanistan where her grandmother lives.

Rosheed is more serious, quieter, with big brown eyes. "Happy," he says when asked how he feels, repeating the answer his father gave.

Azizyar says everything is so different here. He doesn't live in fear. He feels welcomed.

"You have the freedom to wear or do whatever you want," he says. "If my wife doesn't cover her hair and wears the dresses that she likes, she will not be stopped by people pointing at her."

The family has to wait a few hours before they can fully move into their new house, so Coburn takes everyone to a nearby park. Roqia pushes Zainab on a swing and then hops on one herself. Her hijab slips off as she pumps her legs to go higher.

The biggest US resettlement effort in decades

The Azizyars are among more than 70,000 at-risk Afghans who were evacuated from Afghanistan and brought to the United States, according to figures from the Department of Homeland Security. Many of them are temporarily housed on military bases across they country. More than 20,000 have left the bases to start new lives here, with the help of resettlement agencies, according to the DHS.

"These folks need everything. They need clothing, they need food, they need a place to live, they need legal services," said Sister Donna Markham, president of Catholic Charities USA, one of several nonprofits leading the Afghan resettlement process.

The Biden administration has named former Delaware governor Jack Markell the White House coordinator for the Afghan resettlement program, dubbed "Operation Allies Welcome."

In September, Congress passed an emergency funding bill that included $6.3 billion to help Afghan evacuees and resettlement agencies pay for emergency housing, English classes, job training and other needs. The State Department and other agencies have also teamed up with the private sector and nonprofit groups to help Afghans build new lives.

It won't be enough, advocates say.

Markham and other advocates say they've launched massive fundraising and donation drives to try to meet this historic moment.

"The last time we experienced such a massive influx (of refugees) in such a short time period was several decades ago, when more than 130,000 Vietnamese refugees came to the U.S.," says Krish O’Mara Vignarajah, president and CEO of the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, which is helping with the resettlement effort.

"It's essentially a humanitarian disaster response," she says.

The Azizyars and other arriving Afghans will receive a one-time payment of about $1,200 each to get them started, with another $1,000 going to the resettlement agencies for their case management and support services, Vignarajah says.

In Pennsylvania, Catholic Charities has helped Coburn get the Azizyars signed up for food assistance and health care. The family's caseworker is working to get the family U.S. identification cards and plans to provide some English instruction.

"I'd be dead in the water without them," Coburn says of Catholic Charities.

Still, "I'm constantly nervous about, what am I not getting done?" he says. "There's more work and more need than any of us can really get after as private citizens and volunteer groups."

Coburn co-signed the family's lease and put his name on some of the utilities. He has been stocking their fridge and buying the kids everything from swimsuits to action figures and stuffed animals.

Meanwhile, volunteer groups like Task Force Pineapple are still trying to get more vulnerable Afghans out – and keep those left behind alive amid a spiraling humanitarian crisis.

Vignarajah says that in her conversations with Afghan refugees, their first two questions are usually: How can we help family members that remain in Afghanistan in harm's way? And how quickly can they secure a job?

"There are no easy answers," Vignarajah said, particularly to the first question. "It's obviously heartbreaking knowing that close family – siblings, parents, children – are still facing Taliban retribution."

Fresh trauma

A few days after the Azizyars arrived, Coburn went to pick them up at the hotel for dinner.

We can't go out, Azizullah told him. Roqia has been up all night.

Coburn could see she was despondent. She had spent hours on the phone with relatives left behind in Afghanistan. She was consumed with anxiety about their future in a country ruled by the Taliban and an economy in free fall.

She was also sick. Coburn took them to urgent care instead of to dinner.

For Coburn, the Azizyars' arrival has been cathartic, a bright spot in the sea of hopelessness that threatened to consume him after the U.S. withdrawal. He lights up when the kids climb him like a human jungle gym.

"Disney or Sesame Street?" he asks when they crowd together on his couch later that day. "Cartoons!" they reply in unison. He scrolls to YouTube and finds the Dari version, then heads to the kitchen to make Azizullah a cup of chai tea.

But he knows that for the family, the transition has been a fresh trauma after lives filled with violence and fear.

"Most of them have seen more combat in their lives than almost any American," he says of his friend and other Afghan special forces. The family's escape was harrowing, and they were uprooted almost overnight.

"Anybody who has been in a war zone and anyone who has been in a situation where they've had to run for their lives ... they're going to have long lasting, emotional effects that come from that violent situation," says Markham, the Catholic Charities CEO who is also a clinical psychologist.

She said not nearly enough mental health services are available, and that will be one of the major gaps in resettlement.

'The best new Americans'

"This is my room!" Rashid declares. "No, it's my room," his older brother counters.

The boys race through the three-story duplex, exploring the mostly empty rooms, save the donated items lined up along the living room wall. Zainab somersaults across the floor of the back bedroom while her father chats with Coburn on the second-floor balcony.

"You can have your chai out here," Coburn tells his friend.

For now, there's no talk of trauma. Azizullah says he feels happy. And perhaps it's no wonder.

In a few hours, Catholic Charities will deliver nearly everything they need to make the rental house into a home: beds and mattresses, dressers and lamps, cups and plates.

Coburn and his friend join the small phalanx of volunteers moving everything in, assembling the furniture, putting sheets and blankets on the beds. An American flag flaps in the breeze outside.

Roqia explores the kitchen as a guest shows her how to turn on the electric stove. She says their first home-cooked meal will be shorwa, an Afghan stew with meat, potatoes and other ingredients. She will use the oven to bake her own naan, the soft Afghan bread found in bakeries back home.

Azizullah's biggest worry right now is learning English so he can find a job and support his family. He has the skills to be an electrician, a plumber, a truck driver.

"It can be anything," he says. "I'm a hardworking person."

Coburn says the next big step is to get the kids enrolled in the neighborhood school, just a half-mile from the house. He's trying to pace himself, take it one day at a time.

"The Army in me wants to be like: What's next? What's next?" he says.

So what is next? Another Afghan family, a couple who are friends with the Azizyars.

On Nov. 8, Coburn was on his way back to the Harrisburg airport to welcome them.

The man, whose first name is Pashtoon, who was a sergeant major who oversaw the training of Afghanistan's rank-and-file soldiers. (USA TODAY is withholding his last name for the safety of his relatives.) He and his wife, Basira, moved into the third floor of the rental house with the Azizyars.

Pashtoon and his wife speak English well and have already started helping the Azizyars learn the language.

"Every day I’m coming over, and they’re trying out new words on me," Coburn says. "They're tag-teaming everything around the house."

The two families plan to help each other find jobs, pay the $950 monthly rent and adjust to their new lives in small-town Pennsylvania.

Coburn wants other displaced Afghans to relocate here too. It's far less expensive than the urban centers where other Afghan-Americans have settled, he says, and there are more jobs here.

It's a good place for them to become "the best new Americans they can be."

Fatema Hosseini, a journalist for Gannett affiliate NewsQuest, contributed to this story.

Dig deeper into Afghanistan:

Staying could mean death. The escape nearly killed her. How one woman fled Afghanistan for freedom.

How many Americans are still in Afghanistan? State Department number is 'way off,' GOP lawmaker says

With last plane out of Kabul, America's 20-year war in Afghanistan is over

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Afghan refugee family part of biggest US resettlement in decades