What's the perfect gift for an art museum? A rare baroque drawing

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I’m excited to share with all of you, on this day after Christmas, a beautiful drawing that has just entered the collection as part of a generous year-end donation of 36 European and American drawings from collectors John and Sylvie O’Brien.

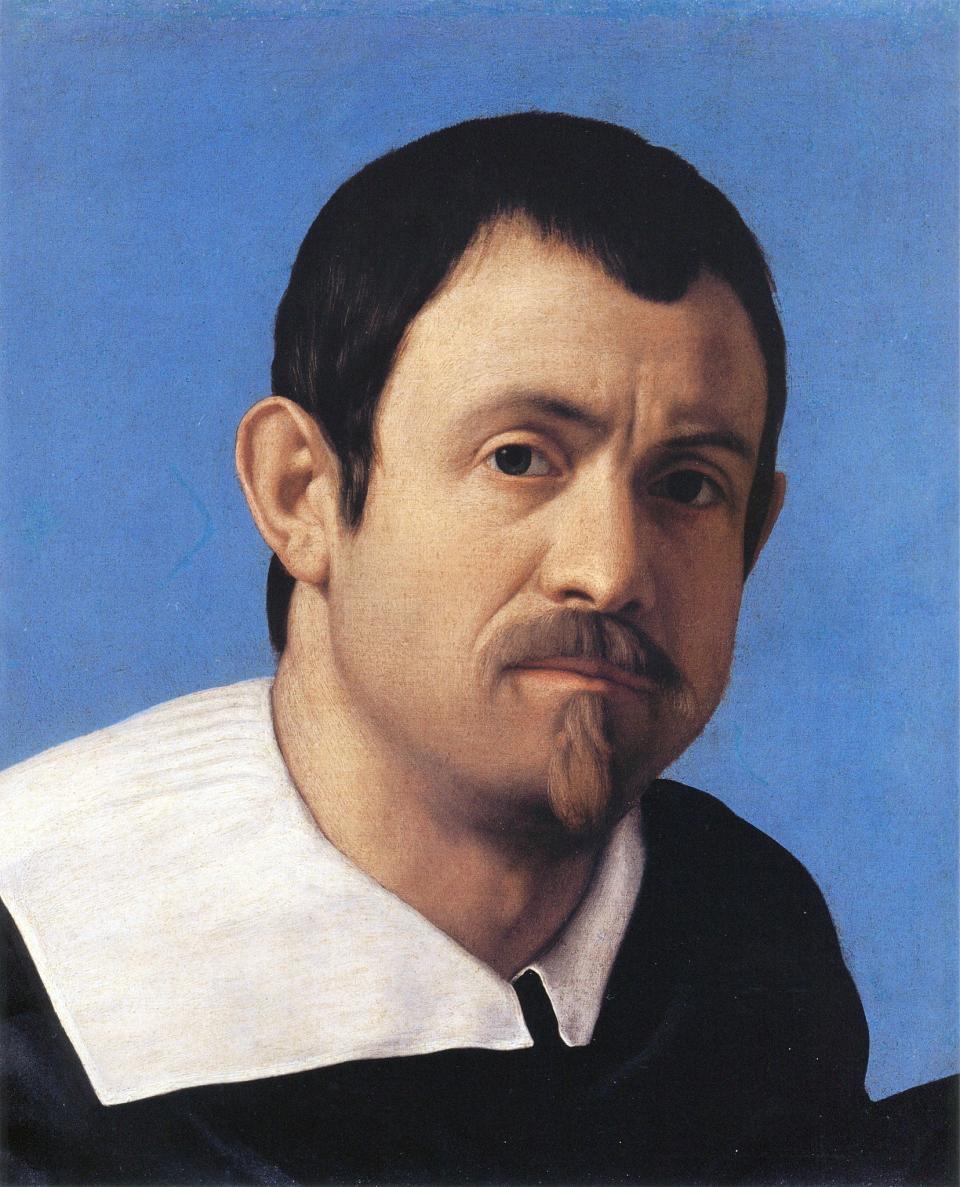

The drawing was made by Italian Baroque artist Sassoferrato (Giovanni Battista Salvi 1609–1685 — known by his birthplace of Sassoferrato, a small town between Florence and Rome). The name may be familiar to some of you because he is the artist responsible for the image of St. Lucy we featured prominently during our summer exhibition Bernini & the Roman Baroque: Masterpieces from Palazzo Chigi in Ariccia.

How truly delightful it is that Hagerstown now has a Sassoferrato to call its own!

Sassoferrato made art that was consciously backward looking. Although he lived entirely during the time defined as the Baroque period, Sassoferrato looked back to the idealized beauty of Renaissance master Raphael (1483–1520) rather than the drama and theatricality characteristic of Baroque art.

His drawings are relatively rare, and most of those known are in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle. They were purchased in Rome in 1768 by Richard Dalton, librarian to George III and an adviser on the formation of the king’s drawing collection.

Sassoferrato was known to often directly derive his compositions from Raphael’s work, and in this case his drawing is based on Raphael’s Madonna & Child (c. 1509), now in the National Gallery London, sometimes called the Mackintosh Madonna.

Raphael is associated with beautiful, humanistic depictions of the Madonna and Christ Child — images in which the madonna appears more like a real mother, and the tender relationship between mother and child is captured. You can see that influence and tradition in this lovely sheet by Sassoferrato.

Sassoferrato’s oil paintings are characterized by their immaculate and careful finish, clarity and sense of color. You can barely see a brushstroke. Here, in graphite on blue paper, we get a much stronger sense of real life than what is typical in his canvases.

Mother love

In this sweet, serene composition, Mary is tender, reflective and slightly sad. Often artists added a suggestion of sadness to Mary’s expression to show her awareness of her child’s fate.

The artist has put all his skills in the service of beauty and harmony — yet we sense movement and weight, and the baby himself feels very real; he is sweetly natural, expressive and loving.

The drawing has a lovely sense of softness in its execution, with subtle modeling that conveys the roundness of the chubby baby and the texture of his skin. The child’s parted lips are a wonderful detail, capturing the evanescence of facial expression.

The relationship between mother and child is emphasized through the composition itself. The two figures together form a triangle or pyramid, a compositional style often favored by Renaissance artists for creating a stable, unified composition.

The one small area of the composition that is not as successful in the drawing is the infant’s bent leg — Mary grasps his foot — but the bend in the leg shows the artist struggling a bit with position and perspective.

Artists used drawings to work out issues of composition and perspective, or as part of the thought process for fulfilling a commission. Here, the drawing has been squared for transfer, meaning the artist has drawn a grid over the composition to allow him to accurately transfer it to the larger format of the canvas.

The detail in Sassoferrato’s drawing and the fact that it is squared indicate it was used as the source for a painting, and we are fortunate in this case to know that the painting has been identified in the collection of the Borghese Gallery in Rome. Another painting attributed to Sassoferrato’s workshop with a similar composition is in the Rijksmuseum collection.

Sassoferrato first began his art education under his father, Tarquinio Salvi, a painter about whom very little is known. Sassoferrato made a specialty of creating beautiful devotional images for private patrons — often images of the Madonna and Child or images of the Madonna in prayer.

Most of his drawings are highly finished and squared for transfer as ours is. Because he worked to satisfy the tastes of his patrons, he often made multiple versions of the same work or variations on compositions. The drawings could therefore have been used to aid in executing multiple works.

No matter your personal religious beliefs, one of the enduring attractions of depictions of the Madonna and Child is the way they capture and celebrate the power of the bond between mother and child — the love, tenderness and safety of a mother’s arms, the possibility and hope embodied in a new life, and the knowledge that these days are precious.

Sassoferrato captures all of that with exquisite softness and grace in this drawing we’re proud to add to the museum’s collection.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Mail: Rare drawing among new gifts to Washington County Museum of Fine Arts