What prior debates reveal about Bloomberg under pressure

At this point in the Democratic presidential primary, most Americans have probably seen a Mike Bloomberg ad on TV. The billionaire former New York mayor has already spent more promoting his candidacy than any other presidential candidate in history: $338.7 million, to be exact.

But on Wednesday night Bloomberg himself will finally appear, live and in person, to debate his Democratic rivals — not just criticize them via flashy web videos. The question now is whether he will live up to his own (very, very expensive) hype.

Not doing so is a real risk for Bloomberg.

“Seeing him up close, he could suffer from a little ‘[Joe] Biden syndrome,’” New York-based political consultant Neal Kwatra, who is unaffiliated in the Democratic presidential primary, recently told Politico. “Most of the country is seeing a capable businessman with short, sweet, pithy ads bombarded all over TV and the internet and there’s a certain brand that’s already emerged. At this stage of the game, anything that contradicts that or undercuts that, it’s dangerous.”

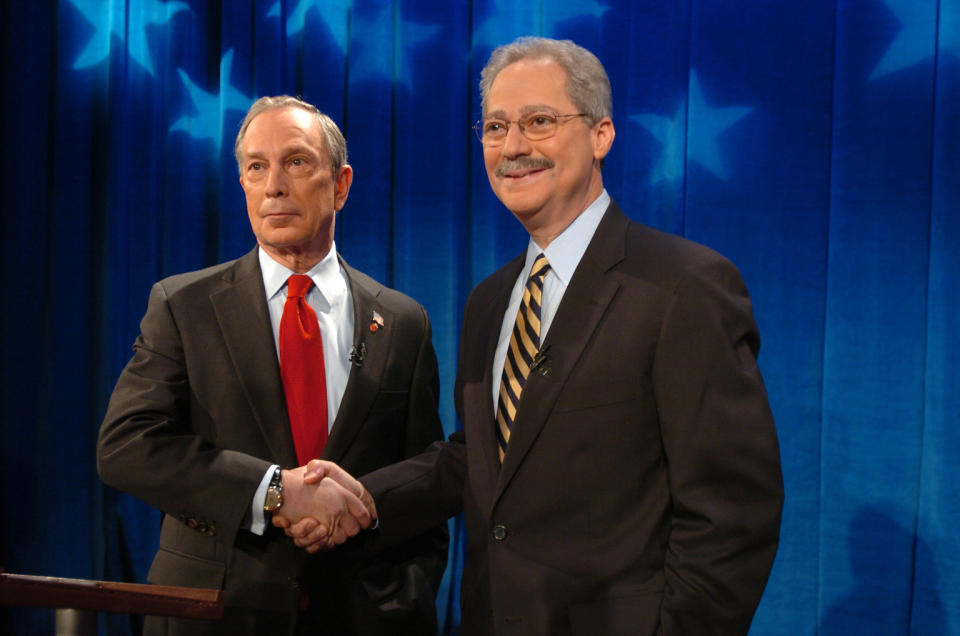

While Wednesday’s Democratic gathering in Las Vegas may be Bloomberg’s presidential debate debut (he qualified Tuesday after cracking double digits in four national polls), he has debated before. In New York, Bloomberg ran for mayor (and won) three times. During those campaigns, he participated in at least eight debates.

To get a sense of what to expect Wednesday night, Yahoo News reviewed hours of footage from 2001, 2005 and 2009. What we found was a dry, deadpan, often dismissive candidate who was far less dynamic on stage than he is in his 2020 campaign’s crisp “Mike Will Get It Done” commercials now dominating the airwaves.

Here are four takeaways from Bloomberg’s previous debate performances that could inform Wednesday’s clash.

He doesn’t make big mistakes

Mayoral debates tend to be far less dramatic than presidential ones, and Bloomberg has never had to deal with multiple rivals attacking him simultaneously on national television. Given his rapid rise to second place behind Bernie Sanders in the national polls — and given his campaign’s recent decision to declare that only he, Sanders and President Trump are still “viable” — that is almost certainly what he will face in Las Vegas.

“It’s a shame Mike Bloomberg can buy his way into the debate,” Elizabeth Warren tweeted Tuesday. “But at least now primary voters curious about how each candidate will take on Donald Trump can get a live demonstration of how we each take on an egomaniac billionaire.”

Even so, Bloomberg tends not stumble on stage (unlike, say, Biden). His situation now most closely resembles his situation heading into his first round of debates in the fall of 2001. Back then, Bloomberg was spending big in his race against Democrat Mark Green. He was gaining in the polls, though still trailing. He was a new face — and, as a Democratic businessman turned Republican candidate competing in a heavily Democratic city, he was seen as an opportunistic interloper. In other words, he had something to prove — just like he does now.

“You don't understand the city just by spending a lot of private wealth in ads in an election year,” Green snapped at one point during the debate. “You understand the city by going to where people live and asking what they need and then reflecting it.”

It was perhaps Bloomberg’s most uneven, unpolished debate performance. As the New York Times later noted, the sometimes imperious entrepreneur indulged all of his least appealing tics: “Sighing audibly, which he does when he is attacked. Gazing toward the heavens, which he does when annoyed by a question. Reciting endless statistical information, which he does almost reflexively.”

Yet Bloomberg also stayed on message, pitching himself, in answer after answer, as a successful technocrat while mocking Green as a career bureaucrat whose experience running the 40-person public advocate’s office couldn’t compare to his own résumé as the leader of an 8,000-person financial-media empire.

A few weeks later, Bloomberg upset Green, narrowly winning his first term in office.

He doesn’t hit home runs

Though Bloomberg has been a fairly consistent debater, he’s also been consistently … boring. Asked in 2001, less than two months after the Sept. 11 terrorists attacks, how he would ensure that New Yorkers are “as safe as possible” — a question prefaced by a clip of a local woman worrying aloud about bombs in daycare centers — Bloomberg passed on a golden opportunity to feel his city’s pain and instead chose to recite a few unsatisfying platitudes: “Get out as much information as you can every single day”; “make sure our police force … takes the appropriate steps to ensure our safety”; and “try to convince people to … go about their normal lives.”

The answer wasn’t wrong, per se, but it is a part of a pattern. On stage, Bloomberg doesn’t emote, or empathize or even attempt to inspire. The last time he debated, more than 10 years ago, Bloomberg was asked — in the final question of the evening — what he hoped to accomplish in the next four years. His answer was comically prosaic.

“So,” Bloomberg said, hesitating briefly before continuing in his signature Boston monotone, “I think it’s more of the same, making sure that we continue the things — making sure that we expand the universe of people that benefit from those things.”

“You’ve been called out of touch with the average New Yorker,” one debate moderator pointed out that year. “How do you feel, as a person, when you hear that criticism?”

Bloomberg paused for several awkward seconds, as if he didn’t realize the question was addressed to him. “Me?” he finally asked, widening his eyes in disbelief. “What criticism?”

The moderator repeated his question.

Bloomberg smirked, shrugged and shook his head dismissively. “I don’t get that sense,” he finally said. Any viewer expecting a deeper emotional connection with the candidate is likely to be disappointed.

Bloomberg even likes to recycle his favorite lines. “Mark, you have a right to your own opinions, but not a right to your own facts,” Bloomberg quipped while debating Green in 2001.

“Let’s take a look at the numbers, Freddy,” Bloomberg said while debating Democrat Freddy Ferrer four years later. “You have a right to your own opinions, but not your own facts.”

He is capable of attacking

Bloomberg can get feisty on the debate stage. And while he never tries to manufacture uplifting moments like Barack Obama or Bill Clinton, he’s usually at his most memorable when he’s on offense.

In his second 2009 debate against rival William Thompson, the city comptroller, Bloomberg turned almost every response into an attack, surprising pundits who expected the incumbent to disengage.

“Give the money back,” he told Thompson when a panelist asked about the comptroller’s decision to accept more than $500,000 in campaign contributions from people who did business with the city. “It just looks terrible, even if it’s not.”

“I can’t keep straight who he wants to tax,” Bloomberg added a few minutes later, noting that Thompson had previously praised the city’s fiscal policies as “prudent.”

“Now all of a sudden he’s running for mayor and he wants to disavow that,” Bloomberg snapped.

Strategically, it’s possible that Bloomberg will bare his teeth again Wednesday night. In recent days he and his team have tried to position the former mayor as the last moderate standing by attacking Sanders directly. Kevin Sheekey, Bloomberg’s campaign manager, tweeted Tuesday morning that “the opposition research on @BernieSanders could fill @realDonaldTrump’s empty Foxconn facility in Wisconsin. It is very damaging, perhaps even disqualifying.”

Even if Bloomberg doesn’t repeat such attacks on stage, he instinctively tends toward sarcasm. In 2001, Green cited a line from page 232 of Bloomberg’s book, Bloomberg by Bloomberg, before stopping to consider the title. “And they call me arrogant!” Green said, laughing at his own joke.

“I don't remember what's on page 220,” Bloomberg replied. “It's not the sort of thing that I spend time —"

Green interrupted with a correction. “232,” he repeated.

“Or 232,” Bloomberg scoffed. Then he grinned. “I'm also pleased that you're able to describe yourself,” he said. “I think a lot of people would agree with your characterization of yourself.”

Mostly he acts like he’s above it all

Criticized repeatedly by Ferrer in 2005 — over his ties to the GOP, his huge campaign spending and his upscale priorities — Bloomberg was “often matter-of-fact and at times declined to engage,” sticking “close to a nearly clinical recitation of his record and plans for the future,” the New York Times reported.

In fact, Bloomberg rarely even looked at his opponent and referred to him by name just once. The closest he came to an attack was when he called the former borough president a “complainer.”

That might be the tightrope Bloomberg chooses to walk Wednesday night in Nevada: brushing off any barbs as petty, intraparty squabbling, pivoting to the larger task at hand (i.e., the need to defeat Trump), while trying to make himself seem bigger in the process.

In 2005, when a moderator asked about a negative comic created by Ferrer’s camp, Bloomberg shot back: “I don’t know that comic books are very important in this election. We should be talking about real issues.”

Expect more of the same Wednesday. The truth is, Bloomberg would “rather be doing other things,” as his media strategist, Howard Wolfson, explained in 2009. “But he understands we’re going to have these debates.”

Or as Bloomberg himself put it last year: “I don’t think the debates really matter that much. It’s good entertainment.”

It remains to be seen whether Bloomberg is right about that. To be sure, the sooner the show is over, the sooner he can return to spending hundreds of millions of dollars to control which version of himself voters see on their screens. But no amount of money will be able to erase a debate debut that falls short of that glossy image.

Read more from Yahoo News: