Weld Street mural keeps memory of slain bodega owner alive

It was the biggest funeral in the history of Rochester's Puerto Rican community, they said.

May 20, 1991. A Monday morning. Six hundred mourners packed closely into the pews of Mount Carmel Church, fanning away the unseasonable heat.

"Everyone here who Emilio Quintana ever did a favor for, please raise your hand," the Rev. Laurence Tracy asked in Spanish.

About 500 people raised their hands.

Mount Carmel was the right place for the funeral. For generations it had been a spiritual home for those who left the island starting in the 1950s. They came chasing the promise that hard work in a cold Northern city would allow them to leave something better for their children.

Most of those Puerto Ricans settled in the northeast part of the city. They rented places to live, enrolled their kids in school and went out looking for jobs. And when they needed, well, anything, they walked down the street to see Emilio Quintana and his brothers.

They were among the first of them. Nine Quintana siblings — six brothers, three sisters — left the small central mountain town of Utuado in the early 1960s and settled in northeast Rochester. Emilio worked as a sanitation worker and then as a taxi driver before the family scraped together to open their first bodega in the early 1980s.

One became two and two became many — as many as 10 bodegas on Hudson Avenue and Scio Street and Clifford Avenue and the corners and commercial corridors that their Puerto Rican community called home.

If the Quintanas were the humble engine of the neighborhood, Emilio was the engineer. He was always at one of the stores or another of his properties, stocking shelves or working the counter or balancing the books.

Neighborhood kids got odd jobs and informal apprenticeships in retail or electrical or plumbing or carpentry. When someone needed credit to buy bread, he gave it to them. If their credit wasn't any good, he gave them the bread anyway.

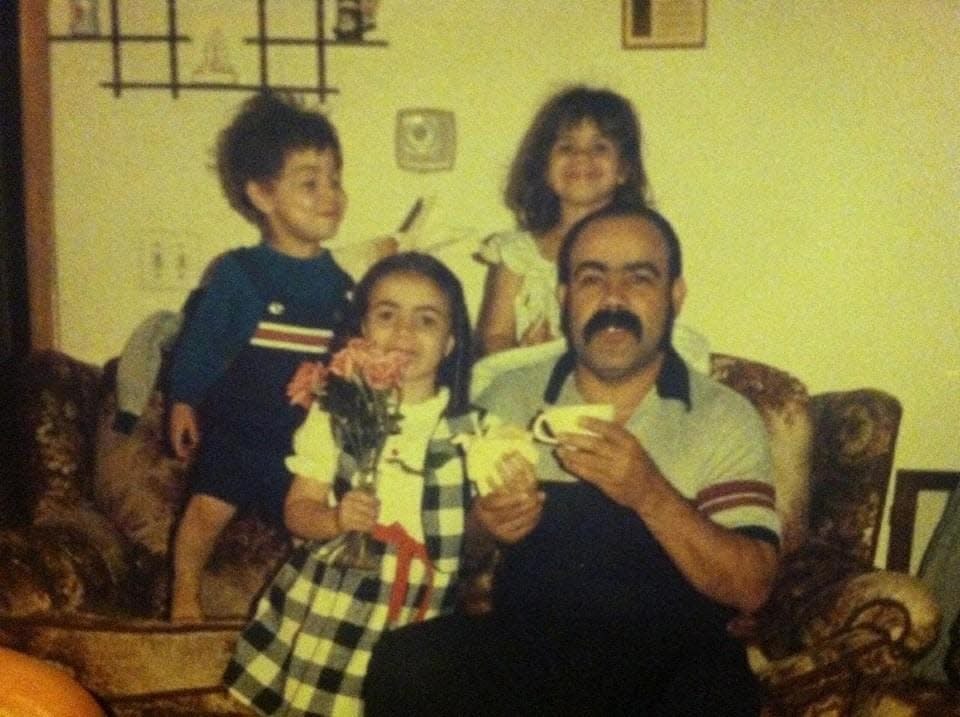

"He was gentle, kind and lovable," his 11-year-old daughter told reporters in 1991. She was one of Emilio's eight children (plus six stepchildren), who ranged in age from 2 years old to 23.

At the front of the church, Nemensio Carrion tuned up his guitar. In Puerto Rico, major community events call for commemorative ballads. The death of "the mayor," as they called Quintana, surely qualified.

Carrion began to sing:

Nuestro pueblo esta de luto

Y toda la vecinidad ...

Hoy yo canto por mi amigo

Bendito Emilio Quintana

Our people are in mourning

And all of the neighborhood ...

Today I sing for my friend

Blessed Emilio Quintana

Rochester robbery gone wrong

The mural was not Javier Quintana's idea. It reminds him of the police tape, and he does not like that memory.

He, his brother and his sister were in the car with their mom to go to the Felix Mini Mart, a bodega at the corner of Weld and North Union streets owned by Emilio's brother Felix. Emilio was considering buying it from him and had spent the evening working there.

When the family arrived, though, the street was blocked off by yellow police tape.

There was a bar next door, so they assumed — hoped — the trouble had been there instead. Nine-year-old Javier and his brother ducked under the tape and ran into the bodega.

There they found Emilio laid out on the ground by the corner of the sales counter, a bullet hole in his head.

It was a robbery gone wrong, police said. They arrested a 16-year-old boy who'd been seen on film in the area but soon released him for lack of evidence. No one was ever charged.

"We all know this is a dangerous business. Everybody always wants to steal from you," said Emilio's brother, Alfredo. "But we have to make a living. Of course, none of us thought it would come to this."

Up until that day, the neighborhood stretching west and north from Weld Street had been safe and familiar territory for the Quintana children.

The crack epidemic was in full swing and its attendant ills in northeast Rochester were hard to ignore. But overlaid on that map of misery was a social network of love and protection.

"Our summers consisted of visiting our aunts and uncles at the stores or sleepovers with our cousins," Javier Quintana said. "They were all spread out but literally in walking distance. ... It wasn't really the safest, but we were kind of insulated, being kids."

The shooting death of Emilio Quintana punctured that insulation irreparably. The 9-year-old no longer could sleep through the night himself but instead begged to be let into his mother's room.

"At that point our lives changed," Javier Quintana said. "I all of a sudden had something I’d never experienced before, which was fear."

Gradually moving out of the neighborhood

On a broader scale as well, the Quintana family reconsidered its priorities. Over the next decade or so they slowly divested themselves of their bodegas and other property in northeast Rochester.

Part of it was natural generational change, with children moving on to careers of their own choosing. But nine months after Emilio Quintana was killed, his ex-wife, Frances Perez, was shot and killed at her own bodega on Hudson Avenue, one of a string of corner store shootings that winter.

"It's getting ridiculous," said Perez's brother, Dionisio Perez. "I own a store on Clifford Avenue and I want to get rid of it."

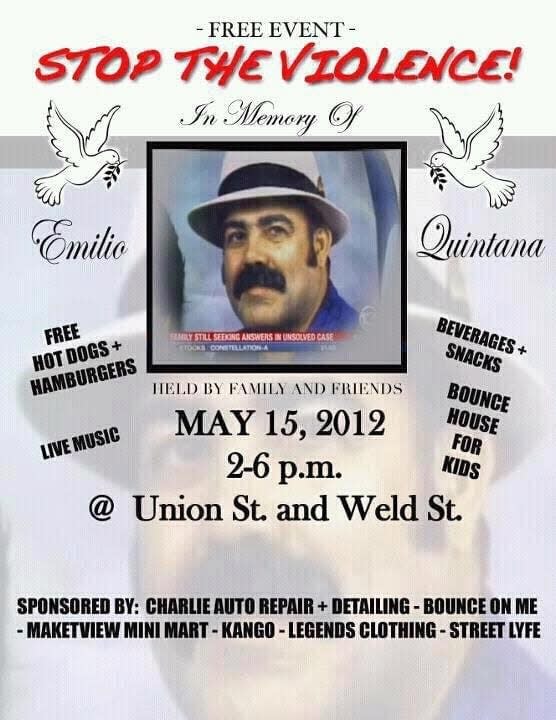

Few shooting deaths leave lasting memorials, but Emilio Quintana's is one. It is the remaining visible legacy of his life and work: a full wall-sized mural on the side of the building where he died, decorated with roosters — a passion of his — and doves and roses.

It was unveiled in 2012, 11 years to the date after his death. There was food and drinks and music and a bounce house for kids.

The family was all there, though few of them still live in the neighborhood. For many, it was one of the few times in the last 32 years they've set foot on the site.

"It took me years as an adult to have the courage to stop and go into the store," said Emilio's daughter, Anabel Brown Quintana. "It was a lot of emotions and I cried when I left. ...

"If I win the lottery, I want to buy that building and knock it down. It's just not good memories for me."

'We're in a bad area, but we fear God'

The bodega at Weld and North Union streets is still open. It's now called Awsan Grocery and is owned by Saleh Ahmed and Andrew Diamond, two brothers from Yemen.

Like the Quintanas, they came to Rochester in search of opportunity. They've run the store since 2005, going through times of prosperity and times of want in those 18 years.

Pallets of two-liter soda bottles run down the center of the store and hats and sweatshirts hang from the ceiling. There's a small section of groceries and a bustling trade in cigarettes.

The cash register today is on the opposite side of the store from when the Quintanas owned it, Diamond said. He sometimes sees people outside lighting candles in front of the mural but doesn't know the full story of what happened to the man who once stood in his spot.

"We’re in a bad area," he said. "But we fear God. We wake up every morning and ask God for safety."

Anabel Brown Quintana asks for safety, too. Anytime she hears gunshots coming from Dewey Avenue she calls her kids and makes sure they're OK. She never stops worrying about something happening to them, too.

"Anytime I can’t get a hold of my children, my mind immediately goes to: 'What happened? What’s wrong?'" she said.

Once, as a teenager, Javier Quintana was hanging out with friends down the block on Weld Street when they suggested going to the corner store. It wasn't until he walked inside that a flood of flashbacks hit him.

"Losing him — the emotional aspect, the financial aspect — those are scars we live with every day," he said. "They shaped us."

'Good, hard-working people in that neighborhood'

Anabel and Javier Quintana believe their father would be proud of how his family has grown and moved forward.

Anabel works in health care now. Javier is a vice president and bank manager at Canandaigua National Bank, where one of his specialty areas is helping bodega owners in the city.

"I felt they’re underbanked and I made it a point to go into neighborhoods that oftentimes bank managers or lending officers ignore and try to gain their trust," he said. " They see me as their banker and someone they can go to. ...

"With the investment in the Inner Loop, hopefully that’ll bring more to the community. And there’s good, hard-working people in that neighborhood. But they need more, honestly."

He doesn't like to go by the store, but he has taken his own children there to see the testament to their grandfather — his place in the community, his hard work and the way he is remembered.

Those visits, like the mural, are a way of passing his memory down to younger Quintana generations and to the neighborhood where Emilio Quintana once stood tall.

"As a bodega owner, you become part of the community. You see these kids grow up and become adults and you see their kids. They come into the store and you chit-chat with them and ask how they’re doing or their mom’s doing," Javier Quintana said.

"We really wanted to acknowledge that legacy and what he brought to the community. Not to highlight my dad’s death … but to make sure his legacy’s not forgotten. And so the community itself can remember."

More Weld Street content, this week and beyond

We want to hear from you to understand what questions and topics you are curious about in your community and on your street. We want to know what you think should be highlighted and known within the city. Email us at MDScott@gannett.com and wramseyiii@gannett.com.

Look for more Weld Street reporting soon on DemocratandChronicle.com.

— Justin Murphy is a veteran reporter at the Democrat and Chronicle and author of "Your Children Are Very Greatly in Danger: School Segregation in Rochester, New York." Follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/CitizenMurphy or contact him at jmurphy7@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: Mural on Weld Street in Rochester keeps memory Emilio Quintana alive