‘We promised to help them’: One congregation’s struggle to bring a Syrian family to America

On the night when the nearly 200 volunteers from the Holy Trinity Catholic Church should have been greeting their family of refugees at the airport, they were at a candlelight vigil instead, praying for the two parents and their six young children, whose flight to a new life had been canceled by a presidential executive order.

The next day, when the volunteers had planned to settle the displaced Syrians into a home filled with furniture they’d collected over months of scrounging, and offering food they’d cooked that would be familiar and comforting, they were walking the halls of Congress instead, pleading their case to anyone in the House or Senate who would listen.

And in the coming days, instead of enrolling the children in school, and helping the father find work, and explaining how to navigate the bus system, enroll in English lessons and find a local mosque, they will be following statements by federal lawyers and judges and White House officials, hoping the legal door stays open long enough for them to get the strangers they all call “our family” onto another plane.

Despite all the talk of refugees since the Trump administration order freezing entry from seven predominantly Muslim countries, little attention has been paid to the Americans who are waiting to welcome them. By law, no refugee can be admitted to the United States without a volunteer organization to sponsor them and nurture them toward self-sufficiency.

At Holy Trinity, a Jesuit parish in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, that group is more than ready, like adoptive parents pacing outside the fully stocked nursery for the child they have never met but already love.

“These are our people, they are our family,” they repeated over and over from one congressional office to the next this week, as well as to each other, almost like a prayer. “We made a promise to help them. Help us keep that promise.”

*****

It all began with that photo — the one taken in late August of 2015, of 3-year-old Aylan Kurdi, in his red shirt, blue shorts and tiny sneakers, face down in the surf on a Turkish beach, after the rubber raft carrying his fleeing family flipped in the waves.

Twenty-five-year-old Chris Crawford saw that photo and decided he had to do something. He was already embarked on a life of service, active in pro-life marches and helping to run a youth ministry at Holy Trinity, which he’d joined soon after college graduation, when he was considering becoming a Jesuit priest himself. After meeting his girlfriend at the church he chose not to enter the priesthood, but he remains committed to Pope Francis’ declarations that being pro-life means protecting all life, particularly and specifically including refugees.

Lauren Roy saw the same photo and was also moved to help. “This breaks my heart,” she told her husband over breakfast that morning. “We need to do something, something real. What can we do?” The couple, both raised and schooled at a Jesuit parish in Seattle, joined Holy Trinity when they moved to Washington in 2008, hoping to raise their five daughters in the same tradition. That afternoon she called Kate Tromble, the pastoral associate for social justice at Holy Trinity, and offered her basement as a new home for any refugee who might need it.

Eighteen months later, Crawford, Roy and Tromble are the coordinators of the Refugee Welcome Project at Holy Trinity, and the first thing they learned was that it’s not as simple as offering your basement. There are nine national voluntary agencies authorized by joint agreement of the State Department and the Department of Homeland Security to resettle refugees in the United States. Anyone entering the country as a refugee must go through one of the nine: the Church World Service Immigration and Refugee Program, the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the USA, the Ethiopian Community Development Council, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, the International Rescue Committee, the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service (LIRS), the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, and the World Relief and Corporation of National Association of Evangelicals.

The groups prefer to settle refugees in neighborhoods where the cost of living is low enough to give a newcomer a good chance at becoming self-sufficient. The greatest number of Holy Trinity’s congregants live in the Virginia suburbs outside of D.C., where rents are more expensive than in much of the rest of the country, but lower than other parts of the area. Tromble called around and learned that the only refugee group working there was Lutheran Social Services (LSS), an affiliate of the LIRS, which settles about 600 refugees in the area every year. So the LSS became their designated partner in this effort.

The next step was to decide what level of commitment the congregation was looking for. There are four, ranging from three months of involvement that mostly includes collecting home furnishings and conducting food drives before arrival, to a full year of involvement, which involves everything from finding and funding housing to offering friendship and help adapting to a new culture.

The Holy Trinity group quickly decided they were in at the highest level. It was “clear pretty early on that accompaniment, walking side by side with a family, was what people felt called to do,” Tromble says. Word spread, and soon they were signing up the first of an eventual 200 volunteers and raising a sum that would reach $60,000, several times the minimum required by the LSS.

Next the congregation had to prove itself capable of meeting the needs of a family that would arrive with next to nothing — a process that included a legal contract signed on behalf of the parish, and an orientation and security screening for all congregants who would come into contact with the newcomers. They were taught the philosophical underpinnings of the program — to make a family self-sufficient, able to pay their own bills and pay back within a year the loan the U.S. government provides upon entry. And they were taught practical matters as well: not to collect a lot of clothes in advance, allowing the family to dress in keeping with their own tastes, traditions and sizes, but to have coats ready at the airport for refugees arriving in winter from warm climates.

Once they were accepted as a co-sponsor, the Holy Trinity team ramped up. The volunteers were divided into committees for housing, transportation, education and food. Arabic speakers appeared from within the congregation, many of them former Foreign Service workers or current language students, who offered to serve as translators. Furniture donations poured in: a law firm that was remodeling its conference room offered what could serve as a large dining table with chairs; a congregant selling a condo provided three cars’ worth of bookcases, desks and rugs; there were bunk beds, and futons, and chests of drawers crammed into congregants’ storage units, basements and garages. An Amazon Wish List, with such items as garbage bags, garbage pails and laundry detergent, was bought out almost as soon as it was posted.

All this preparing took place against the backdrop of the 2016 presidential campaign, as Republican nominee Donald Trump began to speak out against refugees with increasing volume and venom.

“We don’t know anything about them,” he said regularly on the stump. “We don’t know where they come from, who they are. There’s no documentation. Lock your doors, folks!”

The talk worried Crawford. He describes himself as a “single-issue pro-life voter”; he organized for John McCain in 2008 (before he was even old enough to vote) and Mitt Romney in 2012, and he attended the March for Life in Washington every year. But Trump’s statements on immigration, he says, made him realize he could not vote Republican that year.

“He kept promising ‘extreme vetting,’ but I knew all the levels of scrutiny these families were going through, and it was already extreme,” Crawford says. “Only a small percentage meet the existing standards, they have to produce paperwork and documentation and spend years passing interviews and tests,” he says. “I am pro-life, but the pope makes it clear that means all of life. Welcoming the most vulnerable is pro-life.”

It was one thing to decide not to vote Republican, and another to back a candidate who supported the right to abortion. “I went back and forth for weeks,” he said. “Do I vote for Clinton, or do I not vote at all?” Crawford wrote two essays, one defending each option, and sent them to friends whose opinions he respected to debate the merits. In the end, he voted Democratic.

*****

On Nov. 14, six days after the election, the call came. Their case manager at the LSS had news — Holy Trinity had been matched with a specific family. And it was not just any family.

“They said, ‘it’s big, two parents and six children, and the father has a disability and uses a wheelchair,’” Tromble recalls. “Some congregations wouldn’t have the resources to support this large a group, but they thought we could do it. They wanted to know if we were up for it.”

It was as if a prospective adoptive couple got the call that it was twins, or triplets. “We took a deep breath and then decided, ‘Yes, we were called to do this,’” Crawford says.

So now their family had names (which they have asked Yahoo News not to share, to protect their privacy) and ages (the children were 9 months through 12 years when the call came) and the outlines of a life story. They were Kurds who fled to Iraq from Syria in 2014 and registered as refugees with the United Nations. Their application had been in process for more than two years.

“We added them by name to our prayers,” Crawford says. “Until then we had just prayed for ‘our future refugee family.’”

“We started looking for bunk beds, diapers and a crib,” Roy says. “And a wheelchair-accessible home.”

On Jan. 23, three days after the inauguration, the LSS let Tromble know that the family had airline tickets in hand and would be arriving at Washington Dulles International Airport in exactly two weeks. The planning became granular. Who among the group’s members would be part of the welcoming committee at the airport? What foods should be cooked for their first dinner? And there was still the challenge of a home, big enough for eight people and accessible to a wheelchair, that could be rented for $2,500 a month. They had a few possibilities, but each had a flaw; they had not signed a lease yet.

But, four days after that call, the president signed his executive order that severely restricted the entry of passport holders from seven predominantly Muslim countries, stopped all refugee admission for 120 days, and specifically barred the admission of Syrian refugees “indefinitely.”

On an emotional call with their case manager, the Holy Trinity group learned that the family’s tickets had been canceled completely. Since the congregants had made all these preparations, they were asked, might they consider taking another family instead?

“It was like a punch in the gut, a loss, almost like a death,” Tromble says. “We didn’t want another family — we wanted our family.”

“If there was anyone who didn’t think they were ‘ours’ back when we found out who they were,” Crawford says, “the executive order solidified it.”

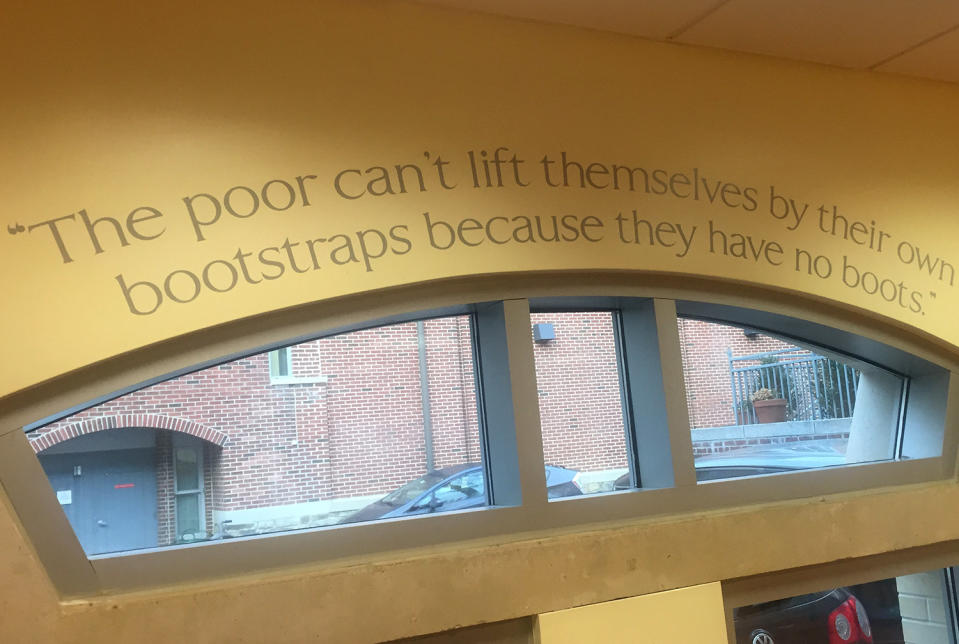

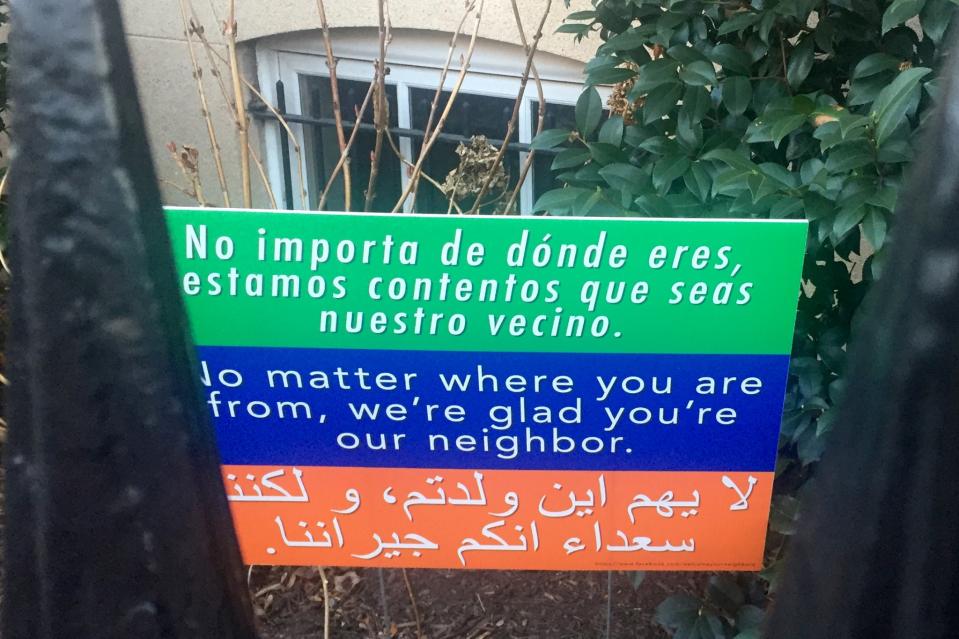

The day the order was issued, Crawford attended the March for Life on the National Mall, holding a sign that said, “I stand with people who are: unborn, undocumented, unemployed, undereducated, unhoused.” The next day he rented a car and drove to Dulles airport to join in the protests. He held a sign there too, which read, “No matter where you are from, we’re glad you’re our neighbor” in Spanish, English and Arabic.

Then he went back to his community and joined the rest of the group in fighting for their family.

Among the requirements for a refugee visa is a connection to someone in the United States. The father in this family had a friend in Arlington, Va. Through that friend Tromble found a cell phone number for the family, now in Iraq, and called it, finally talking directly to the man who until then had been just a name on a paper and a symbol of faith.

The father explained how he had given up the place where he had been living, taken his children out of school and sold everything the family could not carry, all in preparation for their departure for America. He did not know where he might live or how he might survive, now that Syrian refugees were barred “indefinitely.”

“We expected death,” he told Tromble of his journey from Syria. “We didn’t expect this.”

*****

On Feb. 3 a federal judge in Seattle issued a stay against the executive order, which means that had the family arrived on their originally planned date of Feb. 6, they would have been permitted to enter. But because their tickets had been canceled on the ground in Erbil, in Iraqi Kurdistan, as soon as the executive order was issued, they had to wait for the next available flight, which, they were told, was not until Feb. 16.

So at 7 p.m. on Monday the 6th, at the time the original flight was to land, the parish held a candlelight vigil, where an overflow crowd prayed for the family’s safety.

And the next day a group of 20 congregants walked several miles back and forth between the House and the Senate, meeting with aides in six different congressional offices. From Sen. John McCain to Rep. Barbara Comstock to Sen. Patrick Leahy to Sen. Richard Burr, they asked specifically for help in getting the family an earlier flight and more generally that the door be kept open to these refugees and others.

They polished their appeal from one meeting to the next, telling the family’s tale, stressing that they had passed every conceivable barrier and test, including the extra layers already added for Syrian nationals — like retinal scans to insure that the applicant who has been vetted is actually the person getting on the plane.

Linda Wiessler-Hughes, a congregant who retired from intelligence work after 33 years, the last part of which was spent in antiterrorism and antiradicalization work, stressed that no American has been killed in a terrorist attack by any refugee from any of the banned countries.

“Refugees can be our best friends. They are our best way of knowing what is happening in the Muslin community, our best eyes and ears,” she said. “They are also our best ambassadors,” she added. “They spread the word back to their countries that America is a welcoming place.”

And Annemarie Harthun, a lawyer who stepped away from practice to raise her children, stressed that by not being allowed “to care for the most vulnerable,” she and others like her were being “denied the freedom to practice our religion.” After the photo of Aylan Kurdi made its way around the world, Pope Francis urged every parish to shelter a refugee family, and he himself brought a dozen Syrian refugees back on his plane with him after a visit to Lesbos, Greece. “Resettling refugees is how we demonstrate our faith — that is what we are called to do,” Harthun said.

The last stop for the group of 20 was the office of Sen. Tim Kaine. If a rental could be found in Virginia — at this point they had still not found the right home — it would be in Kaine’s state, and the congregants were particularly looking forward to this visit.

They were standing in the hallway before the appointment when the senator himself walked up and said hello. He listened to their story. He agreed that the ban was “outrageous,” and the disruption it was causing was “heartbreaking,” and he promised that his staff would help in any they could.

“We’re Catholics,” he told them. “To call refugees the enemy when you won’t even hold a floor debate on whether ISIL is the enemy, but to call those fleeing for their lives from ISIL the enemy, that is just wrong,” he said. Then he posed for a photo with everyone.

As Kaine had promised, his staff offered to contact the American Consulate in Erbil to try and secure an earlier travel date for the family, but given that there were eight of them, and flights were few, Kaine’s staff was not optimistic.

“Is there anything else we can do to help you help them?” one of the Holy Trinity group asked as hands were shaken and goodbyes were said at the end.

“Pray,” came the reply.

*****

Crawford was up much of the night Wednesday, fielding some emails to prepare for the scheduled arrival of the family the following week, and other emails fretting that a ruling by a court between now and then might upend the plan yet again.

He was so tired at work on Thursday that he left early for home, where he sprawled, exhausted, on his sofa. There were details to be tended to in his inbox — most urgently the fact that a lease had not yet been signed — and a Plan B was forming to use hotels or Airbnb rentals should the family arrive before a more permanent place could be found.

At 6:15 his phone began to buzz with news that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, in San Francisco, had denied the government’s appeal to reinstate the ban. So Crawford stood himself up and got back to work on his computer, newly energized.

“This is a good development, but it’s not over yet,” he said. “I’m not going to exhale until they land next week.” Then he corrected himself. “I’m not going to exhale until we leave the airport and bring them home.”

Read more from Yahoo News: