'We are no different': Inside Huawei's effort to win trust around the world

Huawei Technologies Co., a historically closed-off Chinese telecommunications giant with notoriously reclusive executives, has tried to change its tone in recent months and wants the world to know that it’s just like any other successful company in the West.

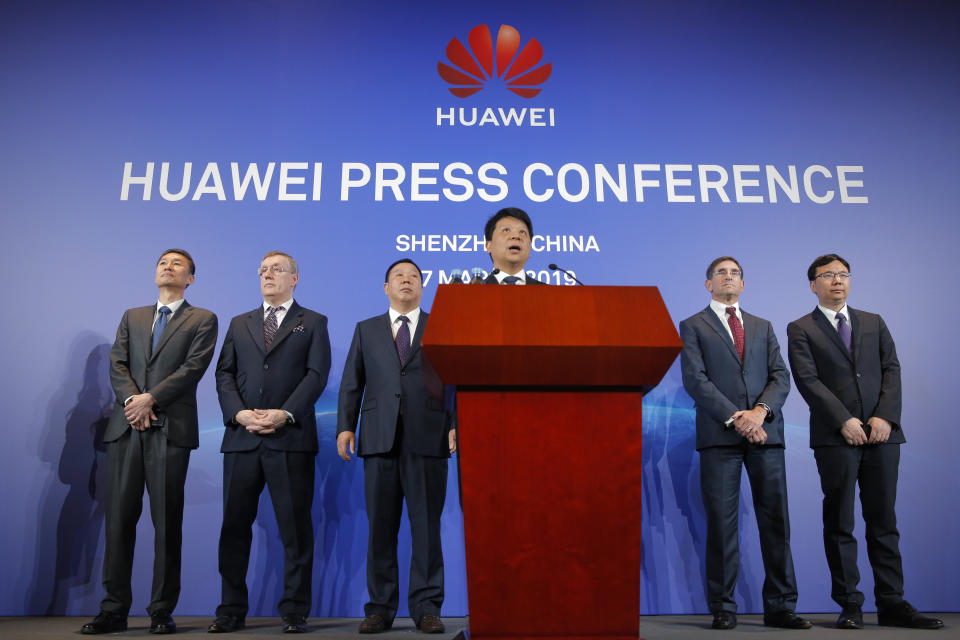

“If Huawei was born in the West, I think our story would be no different from the growth stories of Microsoft, Google and Facebook,” Huawei’s rotating chairman Eric Xu told four Canadian journalists gathered at the company’s sprawling and immaculate headquarters in Shenzhen, China last week.

“There is no difference between Huawei and other Western global companies. We call ourselves a company that brings together the wisdom of the East and the professional management systems of the West… We are no different from Western companies, in terms of professionalism and process-based operations.”

The notion that Huawei is different from other companies, operating under a different set of rules – perhaps even at the behest of the Chinese government – is something the company outright dismisses and is trying to dispel in part by opening its doors to foreign journalists and making its executives available for interviews.

But proving that Huawei is just like any North American company may be a daunting task, given the criminal charges the company currently faces in the United States, an ongoing effort by U.S. officials to convince other countries to join it in banning the use of Huawei technology because of security concerns, and the deteriorating relationship between Canada and China following the arrest of Huawei’s chief financial officer Meng Wanzhou.

Huawei has repeatedly denied accusations that it has close ties to China’s ruling Communist Party, or that its technology provides a potential backdoor for espionage. During last week’s roundtable discussion with Canadian journalists, when asked about what Huawei would do in response to a hypothetical request from Xi Jinping, the leader of the Chinese government, Xu pointed to statements previously made by company founder Ren Zhengfei.

“As to whether Huawei would do that, our founder has made Huawei’s position clear on a number of occasions. We definitely won’t do it,” Xu said. “As he puts it, if Huawei were compelled to do so, he would rather shut the company down.”

Xu also said the company would not violate laws and regulations in the countries in which it operates, which includes Canada.

Scores of journalists have been shuffled through Huawei’s headquarters in Shenzhen, a modern and technological city that, in the 1970s, was a small fishing village home to 30,000 people. Then, in 1980, it was designated a special economic zone that allowed foreign investment. Growth exploded and the city now has a population of 12 million.

Huawei’s welcoming of journalists marks a drastic shift for the company, which for years shunned media attention and kept executives away from any spotlight.

A book about the company that can be spotted on the shelves outside the roundtable meeting called Huawei: Leadership, Culture and Connectivity. It reiterates just how much of a culture shift such media tours are for Huawei. Handed out to journalists during the visit, the book is written by a member of the Huawei International Advisory Council, and it is reflective of the story the company wants the world to know.

‘Like an ostrich hiding its head in the sand’

“Huawei’s chance of success would be cut in half were the media allowed to meddle in the process. Fortunately, Huawei was able to remain level-headed and shy away from the media for nearly a decade,” the book says.

Huawei’s “estrangement from the media” began in 1998, according to the book, when the company’s sales first hit the highest among the four Chinese telecommunication firms and it began to learn “the most from Western companies” by establishing partnerships with telecom operators around the world.

“At that moment, Ren Zhengfei and his company were not thrilled or proud; instead, they felt more lonely, anxious, lost and terrified than they ever had before,” the book says.

“Since then, Huawei had opted for silence, shunning interviews and forums and dodging awards like an ostrich hiding its head in the sand.”

Today, the strategy has clearly shifted. As it fights the U.S. charges and accusations of espionage and insists its technology does not pose a security threat, the company has decided to fight back in a way that it hadn’t bothered with before – public relations.

Outlets from all over the world have seen similar, structured tours that include the opulent and impressive executive hall, the European-style campus in nearby Dongguan (an expansive campus that will soon hold 25,000 employees, literally modelled after several European cities), followed often by the main event: A formal interview with an executive. In between, journalists are taken through campus, shown the cafeterias where employees eat, the mats near desks so naps can be taken mid-day and the labs where artists design phone backgrounds and engineers age-proof 5G infrastructure.

There’s also a casual pit stop at the cafe where employees can get coffee in paper cups showing a lighthouse in front of a bright orange sunset and the words: “The lighthouse is waiting. Wanzhou please come home.”

The public relations blitz is also an attempt to show a side of the company it believes the media and the public – particularly in North America and Europe – have failed to grasp.

“The image of Huawei in the minds of Canadian people is not clear. To a certain extent, they often equate Huawei to China on the grounds that we are a company based in China,” Xu said. He at one point compares Huawei’s troubles to those currently facing Boeing, adding that perhaps two years from now, people will trust the plane maker again.

“I think that is the same case for Huawei,” Xu said. “A lot of suspicions and accusations around Huawei are not built on evidence. A lot of them are based on assumptions, or Huawei’s identity as a Chinese company.”

A Huawei spokesperson, who tours journalists around headquarters a day earlier providing background information and history of the company while also not permitting use of his name for attribution, puts it a little more bluntly.

“Most of the media is somewhat biased. They create their own messages and their own stories,” says the no-name spokesperson.

“Storytelling has never been Huawei’s strength… Having good people who are able to craft a story is a relatively new skill to us. That’s what makes this challenge that we’re in politically so difficult, because the company is literally not structured to be able to respond to it with a coherent message across the organization.”

Canada, China, Huawei ‘all victims of this’

But as Huawei hosted Canadian reporters, relations between China and Canada appeared to further deteriorate in light of the December arrest of Meng, who is also the daughter of Huawei company founder Ren Zhengfei. China has decided to ban $2 billion worth of Canadian canola exports, a move largely seen as retaliation for Canada’s arrest of Meng Wanzhou. A spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry said that Canada should “take practical measures to correct the mistakes it made earlier” in dealing with the overall relationship.

At the same time, two Canadians – Michael Spavor and former Canadian diplomat Michael Kovrig – have been detained in China since December. Canadian officials have complained that the two are being held in response to the arrest of Meng.

In Shenzhen, Xu acknowledged that Meng’s arrest has led to “some misunderstandings” between the two countries, but reiterated that Canada, China, and Huawei “are all victims of this.”

The Canadian government is studying the security implications of highly-anticipated 5G networks and is expected to issue a decision as to whether Huawei technology will be banned in the coming months. Both Telus and Bell used Huawei equipment in portions of their 3G and 4G wireless networks and both have partnered with the company for the deployment of their respective 5G networks.

Xu points to the company’s work alongside Telus, Bell and the Communication Security Establishment (CSE) and Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (CCCS) and a mechanism in place that he says will manage and mitigate any potential risks and concerns around security.

“We understand concerns around cyber security and we think these are legitimate concerns,” he said.

During the tour, media are brought to the company’s Independent Cyber Security Laboratory, where 137 people work testing all of Huawei’s technology. Cyber Security lab director Martin Wang explains that employees who work here have to have extensive expertise and are required to take exams.

He also says that the lab ensures security is prioritized over commercialization of products by providing John Suffolk, the company’s Global Cyber Security and Privacy Officer, with veto power that prevents releases due to security concerns.

With its cyber security lab, as well as its partnerships around the world, the company hopes it bolsters trust people have in the Huawei brand.

“As we say, singling out Huawei will not address cyber security concerns,” Xu said.

“Cyber security will remain an issue that people should be working on for a long time. It required collective efforts from all stakeholders, including the industry, to address it from a legal, regulatory and technical perspective.”

Still, that trust may be difficult to earn.

In the middle of the roundtable, Xu is asked why – given the slew of charges against company and its executives in the United States – Huawei should be trusted. He reiterated that trust must be based on evidence and facts, not suspicions, assumptions “or simply where a company comes from.”

Then, he provided a unique analogy – one where he, as an example, accused the reporter of one day committing a murder.

“I would say you probably will kill someone. Do you believe it? I would say I have a suspicion that you might commit a crime or kill someone someday. That is a suspicion that you could never prove negative,” Xu said.

“You can only explain I haven’t killed anyone in the past and I can guarantee I would never kill anyone in the future, because of my legacy, because of my heritage, et cetera,” he continued.

“That’s also true for Huawei. That’s also what we can do moving forward.”

Download the Yahoo Finance app, available for Apple and Android.