The Water Tap: Another Utah water district advances its reach for water

This article is part of a series addressing topics relevant to water security in southwestern Utah. Look for stories online and in print that feature updates on ongoing water issues, interviews with experts and explorations of how we can ensure a better water future for our growing communities.

In Iron County, the new year kicked off with a new draft Environmental Impact Statement released from the Bureau of Land Management outlining the expected impacts of the region's controversial Pine Valley Water Supply pipeline project. The public will have 45 days, until February 22, 2022, to submit comments on its contents. Feedback will then be reviewed by the agency while preparing the final document.

Comments can be submitted by email to pvwsproject@gmail.com or by mail addressed to the Bureau of Land Management, Attn: PVWS, 176 DL Sargent Drive, Cedar City, Utah 84721. You will be asked to include your name and street address.

The Central Iron County Water Conservancy District (CICWCD), the project proponent, will also host an online meeting for the public via Zoom at 6 pm on February 9, 2022. Register to learn more at the following link: https://eplanning.blm.gov/eplanning-ui/project/1503915/510.

More: The Water Tap: Remembering a year of water, or lack thereof

Highlights of the draft EIS include an Executive Summary that repeats one of CICWCD's central messages over the past 15 years, since they first filed for the legal rights to groundwater in Beaver County's remote Pine, Wah Wah and Hamlin Valleys in 2006:

"Based on an analysis of the Cedar Valley basin demand and projected savings from conservation efforts by the CICWCD, conservation alone cannot overcome the current Cedar Valley basin deficit," the report reads, on page ES-1.

This logic, that conservation alone will never be enough, echoes a statement shared by the CICWCD in an info sheet handed out at its December 2021 public meeting about the pipeline:

"Due to drought, the state’s Groundwater Management Plan, population growth, etc., conservation and reuse are not enough to fix our water resource issues. We must diversify our water resources and extend our reach for water," the info sheet from the CICWCD reads.

More: Iron County water district addresses concerns over water future

This plan — to "reach" for water when local resources run low — has been a strategy common among several Utah water districts that have come under ever-intensifying regional scrutiny recently. The state Division of Water Resources is pursuing a project to funnel water from the Bear River region near Utah's border with Idaho and Wyoming to support growth along the Wasatch Front. And the Lake Powell Pipeline, proposed by the Washington County Water Conservancy District, aims to "reach" 140 miles all the way to Lake Powell in order to sustain St. George's rapid population increase by importing water from the Colorado River.

The Lake Powell Pipeline, projected to cost some $2 billion to build, proposes pumping 28 billion gallons of water to St. George annually from the Colorado River. The plan has been met with widespread outrage by groups both in-state and from surrounding regions who feel that Utah has not done enough to conserve its own local water resources first. This has played out formally on the Colorado River Basin stage in the form of a 2020 letter to the Secretary of the Interior from representatives of the six other states, and less formally via public protests, reports disputing Utah's claim and environmental activism throughout the region.

The opposition to these infrastructure plans amid a record-setting 22-year drought affecting the entire southwestern United States often centers around what many view as Utah's lackluster attempts to reduce water waste or push conservation efforts, while allowing unchecked population growth in water-stressed regions that put Utah communities in a position to reach for new water.

Our analysis of local attitudes: How Washington County residents feel about the Lake Powell Pipeline

Although Iron County's water "reach" is receiving attention on a smaller scale, commensurate with the region's smaller population and smaller pipeline plans — theirs would run 66 miles, deliver up to 4.9 billion gallons annually and cost an estimated $260 million — the nature of the disputes is much the same.

"There’s all this talk about climate change, we’re experiencing drought, we’re in a period of aridification, but somehow we think that a water grab in a community that’s averse to conservation is a project in the public interest? There’s no conservation alternative being put forward. That’s insanity,” said Kyle Roerink, executive director of the Great Basin Water Network, a regional advocacy group.

Roerink's organization, along with the Iron County Water Conservatives and the Utah Rivers Council, filed a complaint last week with the state auditor alleging that the CICWCD did not adequately inform the public of its December meeting about the pipeline plans. Though the meeting ultimately drew some 400 people — more than 10 times the number that tuned in for a virtual meeting about the same project in August of 2020 — these environmental groups argue that this was due to their own efforts to engage the public with the consequences of this project rather than the water district following through on public meeting announcement requirements.

More: Breaking down the Uncertainty, Science behind Pine Valley Water Supply project

Attendees of the December meeting included residents of nearby counties who said they feel they would be negatively impacted by Iron County's plans to "reach" into their local aquifers in order to fuel Cedar City's growth. The Spectrum & Daily News' previous coverage has outlined concerns from a Beaver County Commissioner about how the project is "unneighborly," from a rancher in the valley next to the one slated to be pumped about drawdown of the springs he uses for his animals and questions from the scientific community about impacts to fish and whether or not the amount of water the project has legally been authorized to pump even exists. Nearby Tribes also reportedly have concerns, although they did not respond to requests for comment in time for this story.

“It wasn’t by chance that folks in White Pine County, Millard County, Juab County and Beaver County all got their county commissions to take opposing positions in this fight," Roerink said. "I think we’re going to be seeing their positions spelled out pretty well in the coming months."

Who owns water under the ground? Sister county controversy over Pine Valley Water Supply project

Paul Monroe, General Manager of the CICWCD, however, will remind anyone who will listen that Utah is a "first in time, first in right" state, meaning that water is legally owned by whoever applied for it first rather than whoever lives closer to the source, though this can sometimes mean that the water rights awarded on paper exceed the amount of "wet water" actually available — as Cedar City is finding out under their new state-imposed groundwater management plan.

Monroe disagrees with accusations that the estimates of drawdown in the Pine Valley aquifer as a result of pumping from the project are based on outdated or biased science. He also feels that Iron County is already being proactive about water conservation, and notes that the county was recently ranked fourth in the state for progress on reducing water waste. The draft EIS released this month did not report any major environmental obstacles to the project's progression.

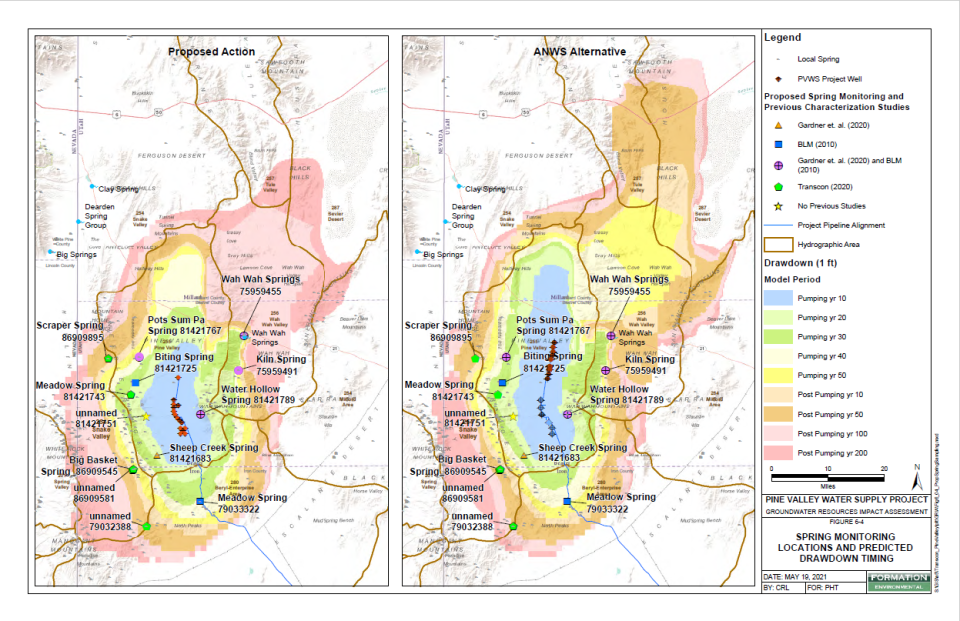

In response to a question about the lifespan of the project, Monroe shared a figure from the 350-page Groundwater Resources Impact Assessment that was prepared for the CICWCD by a company called Formation Environmental and released in December 2021. It shows a map of expected drawdown over the 50-year pumping period and the 200 years that follow for two different project variations that differ slightly in well placement north-to-south within the Pine Valley.

The project currently has a 50-year timeframe because '"the right-of-way grant from the BLM will be for 30 years and they generally have a 20 (year) extension," Monroe explained. After this point, the project will be subject to another environmental review process to evaluate actual impacts.

"We plan on this being a long-term, sustainable project," Monroe continued. "We have been using the latest and best technology and scientists to understand the available water. Based on the current model results, we believe there is more water than we plan on taking."

If at any point the impacts of the groundwater pumping are shown to be greater than what is currently expected, the CICWCD would take action to scale back pumping or minimize consequences, Monroe says. A section of the Groundwater Resources Impact Assessment on "Scoping Considerations" explains it this way:

"[Various legal agreements] would curtail pumping if the safe yield of the basin is exceeded, or prior water rights are impaired. Consequently, the assumption that pumping will automatically continue on the same pumping schedule and in the same geographic distribution was determined to be speculative."

Read our latest investigation: In Utah, while drought and growth leave residents scrambling for water, unknown quantities are quietly diverted off of Forest Service land

Roerink and others who worry about far-reaching impacts, however, remain unconvinced. They believe the likelihood that the pipeline tap will ever be turned off once it is built and flowing is, realistically and politically, very low. And they have not been impressed by their view of the objectivity with which the BLM is weighing evidence for and against the project.

“Our biggest concerns are relating to how the project proponents have forced the BLM to characterize this project in the public eye via the draft that we’ve seen so far," Roerink said. "Their models are putting a small little box around Pine Valley. But just because you draw a box around Pine Valley doesn’t mean that’s how the natural systems underground there operate and function. Just that alone kind of spiderwebs into a number of different areas for concern. Their monitoring and management proposals are really problematic."

It seems, then, that the BLM can expect to receive critical comments on the draft EIS and the project's "reach" from nearby counties, tribes, regional environmental activists, residents of rural Nevada just across the border from where the pumping is planned and even possibly from the National Park Service or other federal agencies worried about a drawdown of connected aquifers reaching into nearby public resources such as Great Basin National Park.

If you want them to also receive comments, for or against the project, from you, make sure to review the document at: eplanning.blm.gov/public_projects/1503915/200379940/20052653/250058836/Revised%20DOI-BLM-UT-C010-2020-0012-EIS_Public%20Comment.pdf and submit your thoughts before February 22nd.

Joan Meiners is the Environment Reporter for The Spectrum & Daily News through the Report for America initiative by The Ground Truth Project. Support her work by donating to these non-profit programs today. Follow Joan on Twitter at @beecycles or email her at jmeiners@thespectrum.com.

This article originally appeared on St. George Spectrum & Daily News: The Water Tap: Another Utah water district advances its reach for water