It wasn't 'extremely unprofessional' to use detailed photos from after Aric Almirola's wreck

Aric Almirola’s unhappiness with the use of close-up photos in the aftermath of his crash at Kansas Speedway is proof of the safety advances NASCAR has made.

After Almirola’s car crashed into Joey Logano and Danica Patrick’s, it came to rest along the backstretch wall at the exit of turn 2. The car’s location provided photographers stationed outside the track’s outer barriers to get detailed shots of the extrication process and included tight shots of the pain in Almirola’s face as he was pulled from a car with a neck brace.

Almirola, who suffered a compression fracture of his T5 vertebra and was alert in the minutes after the crash, called the photos “extremely unprofessional” on Friday morning.

“I’m pretty pissed off about it, to be honest with you,” Almirola said. “I’m glad you asked. I wasn’t gonna talk about it unless somebody asked, but I think that is extremely unprofessional of them. They have no medical expertise whatsoever. They had no idea what was wrong with me. They didn’t know if I was bleeding to death. They didn’t know if I was paralyzed.”

His unhappiness with the photos is understandable. It’s human nature to not want our most vulnerable moments captured in great detail for the world to see. But there was nothing unprofessional about photographers doing their jobs on Saturday night. It would have been far more unprofessional if the pictures weren’t taken at all.

In most all other sports, photographs and video of injured players have become accepted and commonplace. Brutally, it’s become normal to see football players carted off the field after awkward hits.

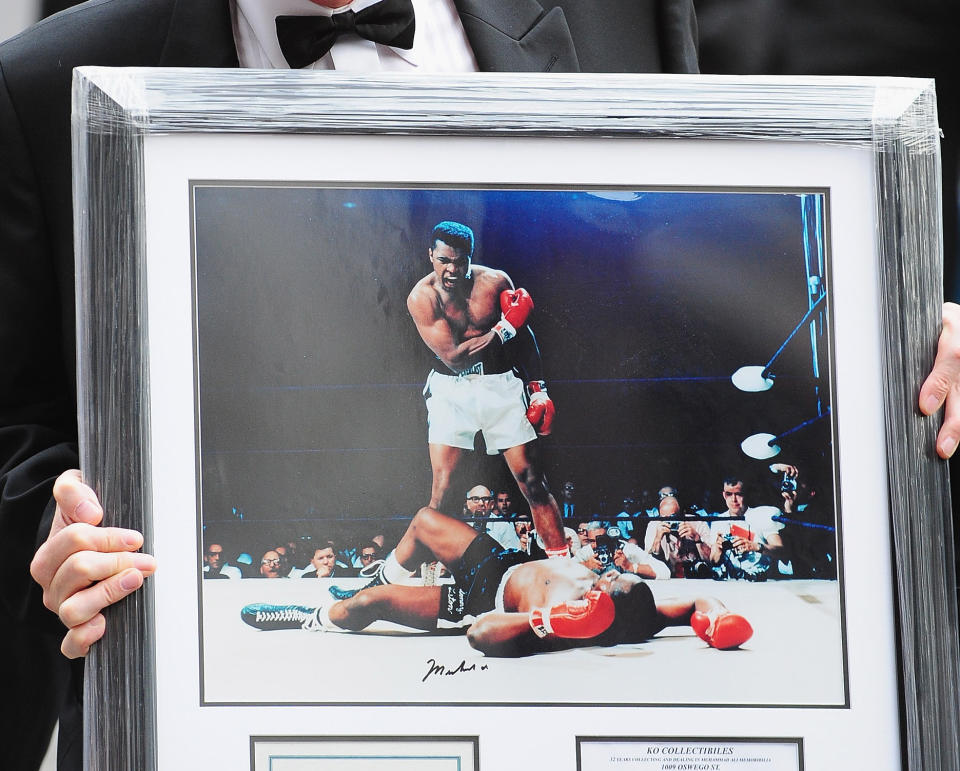

Some of the most iconic sports photos involve injured participants. While we all tend to focus on the pose and facial expression of Muhammad Ali after hitting Sonny Liston, his opponent is sprawled on the ground and not fully conscious.

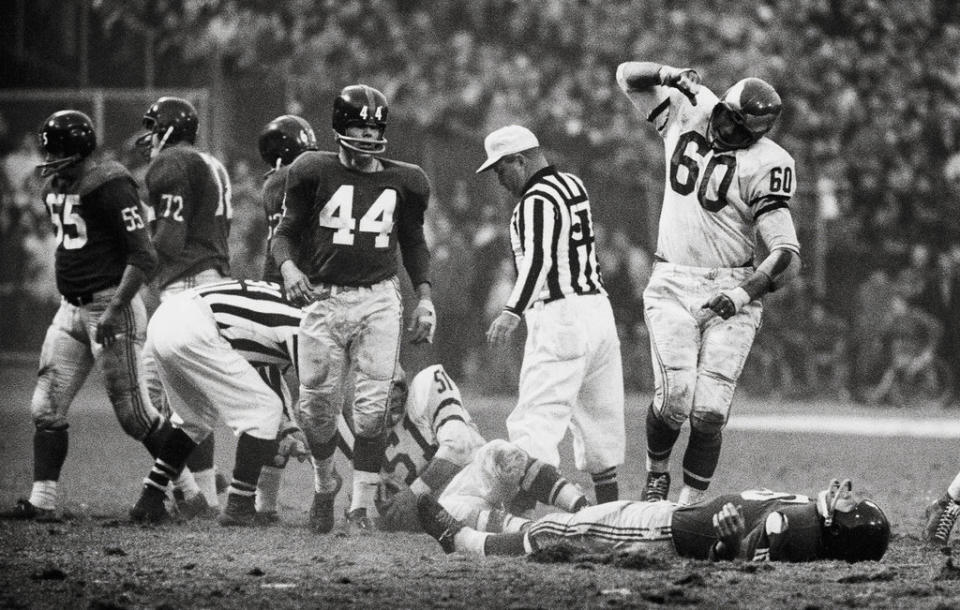

One of the most memorable football photos is of the Philadelphia Eagles’ Chuck Bednarik, standing over the motionless body of New York Giants running back Frank Gifford, who was hospitalized and had to briefly retire after the hit.

And even outside of sports, many of the world’s most iconic photos are graphic depictions of the fragility of our lives. If it was unprofessional to take pictures of Almirola in his car on Saturday night, then the debate should extend to countless other historic photographs.

Pictures can tell a story that words can’t. We can spend hundreds of words trying to explain the pain Almirola showed in his face as workers removed him from his car and placed him on a backboard. Or you can spend a few seconds looking at a photo or two of the scene and understand in seconds just how massive the accident was.

Almirola isn’t the only person who has taken issue with usage of the photos. Earlier in the week, Dale Earnhardt Jr. said it was in “poor taste” to use one of the photos of Almirola.

Just me? Or is it quite a bit in poor taste to use such a photo. ???????? pic.twitter.com/UH3RgX4ONe

— Dale Earnhardt Jr. (@DaleJr) May 16, 2017

His sentiments were echoed by others in the sport, including Indianapolis 500 winner Dario Franchitti.

The photo called into question by Junior came in an article dated three days after Almirola’s crash when the extent of Almirola’s injuries was known. Curiously, there has been little, if any, outrage toward Fox’s coverage of Almirola’s accident. In the moments after the crash the severity of Almirola’s back injury was unclear. But Fox provided live video shots of crews removing Almirola from his car and even showed crews rolling him on a backboard from his car to a waiting ambulance.

Like with still photography, Fox’s live video gave fans a better idea of what Almirola was going through than what could be described with words.

As safety and knowledge attempt to advance, sports participants and fans understand there’s an inherent physical risk in every event. A basketball player could tear an ACL in front of 20,000 fans and millions watching at home. A baseball pitcher could sustain a season-ending elbow injury during the World Series.

Injuries and the public pain that comes with them is part of the social contract for athletes who are public figures. Getting paid more than 99 percent of the world’s population to perform in front of thousands of adoring fans means the bad moments are public along with the good ones.

Admittedly, racing carries a higher level of worst-case risk than stick-and-ball sports. Death is an unavoidable part. While racing-related deaths have plummeted in recent years, one is still one too many.

But even as drivers like Junior (concussion), Kyle Busch (broken leg and foot) and Denny Hamlin (broken vertebra) have sustained serious injuries in the last few years, injuries aren’t nearly as common as they could be — and likely why Almirola is unhappy. It’s far more surprising when a driver doesn’t get up and walk away from a hard impact with another car or the wall than when he or she is released from the infield care center in a matter of minutes. Fans and drivers aren’t desensitized to regular injuries.

That’s a great thing. Almirola’s crash was the first time in over 10 years in the Cup Series that the roof had to be cut off a Cup Series car to get a driver out. For a sport whose icons all have accident horror stories, the relative health of its current stars is quite remarkable and worth noting.

But it’s also worth noting when injuries do happen. Much to his chagrin, the pictures of Almirola are the most recent reminder that racing can still be a brutal sport and is much more than people driving cars in circles. It’d be a shame if they didn’t exist.

– – – – – – –

Nick Bromberg is the editor of Dr. Saturday and From the Marbles on Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Email him at nickbromberg@yahoo.com or follow him on Twitter!