Warm ocean water is melting East Antarctica's largest glacier

Right now, a team of about 30 researchers are sailing through the turbulent waters of the Southern Ocean aboard an Australian research vessel named the "Aurora Australis," hoping to collect vital intelligence on East Antarctic glaciers.

Their work on prior missions has already revealed some unsettling results.

The information these scientists gathered during the Antarctic summer of 2014 and 2015 makes clear that glaciers and ice shelves in East Antarctica are vulnerable to some of the same forces that appear to have set into motion an irreversible melt of parts of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet in the Amundsen Sea.

SEE ALSO: Large parts of West Antarctic Ice Sheet could collapse 'in our lifetimes'

The data could go a long way toward helping researchers understand how vulnerable the vast ice sheets located in what was once considered the stable part of Antarctica are to melting.

A new study, which was the result of the Australian-led research cruise in 2014 to 2015, was published in the journal Science Advances on Dec. 16. The team's data found that relatively warm waters rising from deep in the Southern Ocean are moving underneath the Totten Glacier through two undersea channels. These channels are effectively melting the glacier from the bottom up.

The glacier contains enough ice volume to raise global sea levels by 3.5 meters, or 11.5 feet, if melted.

Image: Paul Brown

These channels are acting as warm water veins, moving modified ocean water from the depths of the Southern Ocean inland, where it is melting the underside of the ice.

These warm water channels are eating away at the ice from below the surface, thinning the floating ice shelf and making it easier for the inland glacier to slide into the sea.

The observations helped confirm hypotheses that researchers developed from looking at satellite and aircraft-based evidence.

"We knew from satellite data that the Totten has been thinning faster than other glaciers in East Antarctica, but we didn't know why," said Steve Rintoul, the interim director of the climate science center at Australia's CSIRO research institution, in a statement.

The ship's observations of the sea floor and base of the Totten Glacier, along with ocean temperatures and the flow of ocean waters, helped fill in the incomplete picture that scientists had. They hypothesized that the ocean was causing some of the ice loss seen in satellite data, and the observations confirmed their hunch.

"We discovered a large channel in front of the western side of the Totten Glacier which is around 10 kilometers wide and up to a kilometer deep," Rintoul said in the statement.

"We found that warm water is reaching the ice shelf through this channel, with temperatures high enough to drive rapid melt of the underside of the ice shelf."

Richard Alley, an ice sheet expert at Penn State University who was not involved with the new study, said the research confirmed the predictions and hypotheses from the researchers. "[It's] worth pointing out that this is real science," he said in an email,

"with predictions/hypotheses and confirmation."

"Measurements showed that the base of the ice shelf is melting rapidly. Assessment of possible energy sources gave high confidence that the ocean is responsible, which requires a strong inflow of relatively warm waters, with geophysical data indicating a likely path for that inflow," Alley said.

He says the study adds to existing knowledge on East Antarctica by providing a better understanding of the depth of water under the ice shelf and glacier, which should help scientists better predict the future ice melt.

Removing the door stops

Ice shelves like the Totten Ice Shelf, which are floating areas of ice attached to land-based glaciers, act as doorstops or plugs that hold back the flow of ice from moving into the ocean.

When ice shelves are weakened, either by surface or subsurface melting, or both, then land-based glaciers can advance more rapidly into the sea. This adds water to the oceans, raising sea levels. Many Antarctic glaciers are already in the throes of more rapid movement into the sea, such as Thwaites and Pine Island Glaciers.

"Looks like a nice study confirming that Totten could easily be as much of a risk as the Pine Island Glacier and Thwaites in West Antarctica, even though losses presently are not as high," said Ian Joughin, a researcher at the polar science center of the University of Washington, in an email. Joughin was not involved in the new research.

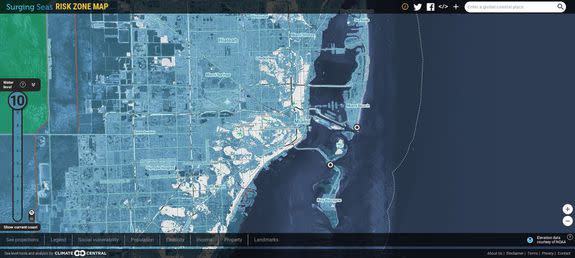

Image: Climate Central

"It certainly could be a concern for those in low-lying areas of Florida and elsewhere who already [are] contending with the effects of rising sea level," he said.

Other sea level rise experts also consider the new study to be important and concerning. Eric Rignot, a climate scientist with the University of California at Irvine and NASA, told Mashable in an email that the new study is "a game-changer" for research into this part of Antarctica.

"The fact that Totten and several other East Antarctica glaciers in that sector are already losing mass and thinning dynamically (i.e. Flow too fast), is a ringing bell that East Antarctica is not immune to change and may be as vulnerable in the future as west antarctica," Rignot said.

"The new data put Totten among the most serious threats of rapid seal level change in the coming century from Antarctica," Rignot said.

On the current voyage, Rintoul is hoping to get more information on exactly how ocean waters that are capable of melting ice are being brought up from the deep ocean, according to a press release from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation.

"Understanding the physical processes delivering heat to the ice shelf will help us assess the vulnerability of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet to future changes in the Southern Ocean," Rintoul said.

According to Alley, the evidence-to-date shows that East Antarctica will be a significant, though not necessarily dominant, contributor to sea level rise in coming decades.

"Many lines of evidence have been coming together that under strong warming we will commit to large sea-level rise, with some East Antarctic ice contributing," he told Mashable.

"The rate of rise from East Antarctica is still expected to be slow compared to the decades-or-less timescales that primarily concern economists, but contributions may already have started and could indeed matter at least a little in that 'economic' timescale, and much more over multiple generations."