Virginia school board restores Confederate names

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Crews work to remove a statue of Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson in Richmond in 2020. (Ned Oliver/Virginia Mercury)

Proud and satisfied, or sad and embarrassed.

However citizens of the commonwealth view Shenandoah County School Board’s recent decision, Virginia appears to be the first in the nation to restore Confederate school names, after years of vigorous community engagement, a controversial renaming process, and a change in board priorities related to race, diversity and inclusion.

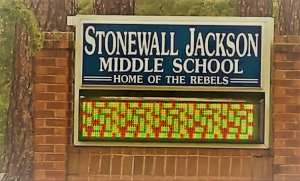

On May 10, the Shenandoah County School Board reversed a 2020 decision by a previous board to rebrand two schools previously named after Confederate Generals Turner Ashby, Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. In 2021, the schools on the division’s “southern campus” that included North Fork Middle were renamed from Stonewall Jackson High School to Mountain View, and Ashby-Lee Elementary School to Honey Run.

To some, the Confederacy represents a heritage of Southerners’ courage against the federal Union and fighting for the rights of southern states. Others view the Confederacy as defenders of slavery and a foundational aspect of America’s history of racism.

Four days after the decision, when Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin was asked by a reporter to comment on the reinstated Confederate school names during a press conference following the passage of the state’s two-year budget, he said he was unfamiliar with the topic. He added that he believes those decisions are at the discretion of the local school districts.

“I’ve been very clear all along that we need to teach all of our history, the good and the bad, that we can’t know where we are going unless we know where we’ve come from, but to the specifics of the decision, you’ll have to forgive me because I haven’t been very close to them,” said Youngkin.

Virginia House Speaker Don Scott, D-Portsmouth, commented on the Shenandoah school names the day after the board made their decision, calling it “outrageous.”

According to recent data from the Department of Education, white students make up most of the total student enrollment in Shenandoah schools at 73%, ahead of Black students at 2.9% and Hispanic pupils at 17%.

“I feel really sad for the students, both Black and white and Latino, who have to deal with leadership that is backwards looking and not forward looking, that doesn’t believe that the Confederate names for those schools are wrong,” Scott said.

“But we will continue to fight to make sure that the real history is known and that we will get better from it.”

According to Beau Dickenson, a former teacher of American History at Shenandoah County’s Stonewall Jackson High School, public schools, particularly high schools, began to be named after Confederate between the 1950s and 1960s, as the Civil Rights Movement swept through the nation.

Many localities named their schools after Confederate leaders in response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case mandating desegregation.

During the 1950s, school boards and lawmakers, including Virginia’s U.S. Sen. Harry Byrd, were fighting against the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision to desegregate schools, a strategic effort known as Massive Resistance.

Virginia pushed back against integration by cutting off state funds for integrated schools, issuing tuition grants to white children to attend segregated private schools and closing public schools to prevent desegregation in Charlottesville, Front Royal and Norfolk.

Dickenson said one of the school closures near Shenandoah was in neighboring Warren County, which he believes made school boards aware of why the schools were closed, adding that the news was also featured in the Northern Virginia Daily newspaper for both communities to read.

During this time, Shenandoah leaders named one of its high schools after Stonewall Jackson, on Jan. 12, 1959. Jackson was famously known for leading Confederate soldiers in Shenandoah County and working under Gen. Robert E. Lee during the Civil War.

Days later, federal and state courts ruled that closing schools was illegal. However, Massive Resistance was not declared illegal by the Supreme Court until 1968, a ruling stemming from the Green v. County School Board of New Kent County case.

“The convergence of all those forces makes it abundantly clear, I think, that this naming was politically motivated,” said Dickenson.

Over the last four years, localities statewide have made a concerted effort to address the commonwealth’s history of white supremacist ideology and historical practices of creating unfair advantages for white people by implementing policy changes and hosting community discussions on these topics. Several communities renamed roads that bore the names of people connected to slavery and removed signs and symbols of the Confederacy, such as statues.

The 2019 candidates’ forum

In Shenandoah County, the controversy around the school names has been discreetly discussed in smaller groups for years. But one of the most notable times the question about changing the Confederate names surfaced publicly was during a District 2 school board candidates’ forum in October 2019.

Marty Helsley, who was then a candidate for the Shenandoah County School Board, fielded a number of questions, including ones about his interest in changing the high school’s name from Stonewall Jackson, which he opposed, according to The Northern Virginia Daily.

“This valley is rich in Civil War history,” Helsley said during the event. “Stonewall Jackson, if you are an expert in Civil War history, was a fine gentleman. Apparently, the School Board then decided to name the school after Stonewall Jackson for excellent reasons and it should stay that way.”

Helsley on Monday, May 20 denied the remarks attributed to him by The Northern Virginia Daily.

“My response, if I recollect, said ‘I will look at the merits when it comes up,’ something to that effect,” said Helsley.

In November 2019, Helsley was elected to office, joining a group predominantly composed of former educators and parents of school-aged children including Shelby Kline, Andrew Keller, Michelle Manning, Cindy Walsh and Karen Whetzel.

Walsh said when she joined the board in 2016, the board was focused on addressing local issues.

But things started to change between 2015 and 2020, she said, after a series of events: a white nationalist killed nine worshippers at a historically Black church in Charleston, South Carolina; hundreds of white nationalists marched through Charlottesville and clashed with counter protesters, killing one and injuring 19; and the killing of unarmed Black man George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer.

“Gradually I would hear from people more about how inappropriate the names were on the southern campus, but it was still relatively quiet the first couple of years,” Walsh said.

She said even though Shenandoah County didn’t have a lot of racial incidents, eventually it “felt like the right thing to do, to nip it in the bud and take care of getting those names off of those schools.”

Manning said after listening to her board colleagues and school staff talk about the struggles that they observed from dealing with students during a “fragile emotional time” in middle and high school, something needed to be done. She voted in favor of removing Confederate monikers from the schools.

“It just seemed like it was the thing to do and, and I don’t regret my vote at all, because I still feel to the core of my being that it was the right thing to do for students,” Manning said.

In a June 2020 resolution, leaders from the Shenandoah County Board of Supervisors and School Board condemned racism in separate resolutions. The school board did not stop there.

The renaming process

On July 9, 2020, Whetzel and Walsh, who served at the chair and vice chair on the board, agreed to add an item to the board’s agenda to retire the school names of Stonewall Jackson High and Ashby-Lee Elementary, and the rebel mascot at North Fork Middle School. The measure passed in a 5-1 vote.

Shenandoah retired the name — joining Prince William County, which had two schools bearing the same name — in June 2020.

Helsley was the only member to vote against renaming the schools, according to minutes from the meeting.

The meeting, which was virtual, created friction between the public over the process and perceived lack of public participation. The board allowed speakers to respond to the motion, but diverted from its common practice of waiting a month before taking action, according to Helsley. Some community members took issue with that.

“We had a problem with the lack of process and the lack of public involvement,” said Mike Schiebe, a spokesperson for the Coalition for Better Schools, made up of county residents that formed after the decision.

“We didn’t have a chance to really be involved and that upset a lot of people in Shenandoah County,” he added. “So it proved to be very divisive.”

During an in-person Sept. 10, 2020 meeting, the board reaffirmed its vote and, in a resolution, outlined a plan for renaming the schools and finding a new mascot for the middle school. The board also added language in the resolution to include public input into the decisions.

Walsh said changing the names cost money beyond the signs outside the school, “things that you wouldn’t think of,” from stationary and uniforms to gym bleachers, to name a few. She said it cost a little over $300,000, much of it from the districts’ savings, not its operating budget.

As the resolution stated, “under no circumstances shall this motion be construed as requiring the expenditure of funds that have not been appropriated to the Shenandoah County School Board for the current fiscal year.”

Opponents of the name change argued that the board said taxpayer dollars would not cover the schools’ name change costs.

However, Walsh and Manning said the funds were from the board’s savings and donations collected during the pandemic, when the Shenandoah Valley Regional Program for Special Education program was not in operation.

That mirrors the cost breakdown presented in a March 11, 2021 board presentation, which showed that the costs were covered by $135,000 from unused salary accounts for frozen positions, and $133,284 from residual Shenandoah Valley Regional Program for Special Education tuition. Manning said Shenandoah Forward, which she and others founded, raised the remaining amount, under $40,000.

Walsh said it was common for the board to spend funds from the board’s savings on one-time expenses, such as capital projects, and not recurring ones, such as teacher salaries.

On Jan. 14, 2021, the board accepted the new names of the two schools. The next month, the board selected the generals as the mascot for both Mountain View and North Fork.

In the months following the vote to retire the names, board members faced a recall, some received threats by email and phone. Another member expressed that their mailbox was knocked over by a truck.

According to state law, elected officials can be removed from office by a circuit court through a petition for “neglect of clear, ministerial duty of the office, misuse of the office, or incompetence in the performance of the duties of the office” when it has a material adverse effect upon the conduct of the office.

Board members said it was upsetting to be considered for a recall because it meant that the petitioners — some of whom they knew personally — believed they were not doing their job properly.

Whetzel, who had just lost her husband after 47 years of marriage, was the only member that received enough signatures for a recall. Her board term ended before any action was taken in court. The case was dismissed.

“I told myself, some of [the petitioners] just think they’re signing [a sheet] that they’re against the name change, and I respect that,” Wentzl said. “So that might have been my way of dealing with it because it’s not fun to be served petitions for your removal.”

Schiebe said he’s well aware of the local historic connections to the previous names, but he said the coalition’s main problem was with the board’s approach to retiring the names.

“There’s a lot of people who are really focused on the names and what they are, and in our group, if the public was polled, and if the community as a whole decided we want to change the names or whatever, we would have accepted it,” Schiebe said. “We’re more focused on the process and our lack of involvement in our own government, which is … one of the cornerstones for our democratic process and of our constitutional rights.”

A change

In 2021, the school board’s decision to rename the schools led to a unified effort by county residents to overturn the board’s action. Others made their voices heard at the voting polls, selecting candidates that shared their views.

Now, four years after the vote to retire the Confederate names, the makeup of the six-member school board has been completely overhauled following two elections. The new members are Dennis Barlow, Kyle Gutshall, Brandi Rutz, Thomas Streett, Gloria Carlineo and Michael Rickard.

All of the members of the 2020 board, who started their terms at different times, completed their terms and did not seek reelection.

In 2022, Barlow, Gutshall and Rutz joined the board for the first time and soon had an opportunity to weigh in on restoring the Confederate names, but a measure to do so failed in a 3-3 vote. The failed measure would’ve included a plan for the school to pay thousands for a community survey about the issue to be conducted.

Helsley, who initially was not in favor of changing the Confederate names, voted in 2022 to keep the names Mountain View and Honey Run. He said his vote was in the best interest of the students.

“I saw no need to reverse back to put the Stonewall Jackson [name] back,” Helsley said. “That did not sit well with the group that wanted to put it back.”

But in 2024, the board’s ability to restore the names changed when three new members joined, replacing the remainder of the 2020 board.

Schiebe said the Coalition for Better Schools did not endorse any candidates, but some members did support them individually. He said the coalition has had about 20 volunteers working to provide information to the public and has hundreds of supporters.

The coalition received overwhelming responses in favor of restoring the Confederate names, Schiebe said, after the group conducted two controversial surveys. Some argued the results came from a portion of the county and not the whole county. The mail-in survey produced a response rate of about 13%.

However, the board ultimately voted 5-1 to restore the Confederate names, agreeing to use only private funds for the restoration costs after the meeting extended until the next morning.

In a letter to the board, the coalition said the legacy of Stonewall Jackson, “while complex, remains an important part of our local history,” and described Ashby and Lee as “prominent figures and local heroes.”

Gutshall, who represents constituents in District 4, which isn’t where the schools are located, said they overwhelmingly supported retaining the school names Mountain View and Honey Run but respected their colleagues’ viewpoints.

“I don’t feel like I would be doing my job properly if I sat here and ignored them, even if I didn’t necessarily agree with what they were expressing to me,” Gutshall said.

Board members’ decision was partially informed by the previous board’s “lack of process” when it changed the school names in 2020. Others argued that the agenda was published over the Fourth of July weekend and did not provide enough time for the public to respond.

“How it was done in 2020, it was not done right,” said Board member Thomas Street, adding that it was secretive and a “knee-jerk” reaction. “I was very disappointed in that leadership.”

District 3 School board member Gloria Carlineo added “This was not an innocent mistake by some inexperienced school board. No, this was a carefully choreographed machinations of a school board colluding to ignore the people they represented.”

Schiebe said the coalition was happy with the board’s decision and hopes to help with the fundraising.

Board Chair Barlow said the school board expects the renaming transition to be completed by July 1, but is in no rush, the Northern Virginia Daily reported. The school division retained some items with the Stonewall Jackson name that are in storage.

The blueprint?

With the board’s success in restoring the Confederate school names, some lawmakers and supporters are embarrassed and concerned that it could be a regressive blueprint for other localities.

“It can always happen elsewhere. We are a democracy. No matter how backwards your views are, you can vote… but we’re gonna continue to do our best to educate and advocate for what’s right,” House Speaker Scott said.

In Richmond, lawmakers including Sen. Mamie Locke, D-Hampton, said the board’s decision to revert back to the original Confederate names was not a surprise because the candidates being elected have “no commitment” to diversity, equity or inclusion, which “flows from the top of [Virginia’s] gubernatorial administration.”

Locke, who serves on the Senate Health and Education committee, said across Virginia school board memberships are changing, resulting in some that are “stuck in time” and are more interested in “revisionist history” than supporting the best interests of children, teachers and the schools.

“This whole revisionist history idea is what is driving renaming schools to the names of Confederate generals and paying homage to a lost cause.”

In 2020, Locke along with Del. Delores McQuinn, D-Richmond, carried successful legislation that gave localities the authority to remove or relocate war memorials, such as the vaunted Monument Avenue statues of Confederate army leaders.

Del. Candi Mundon King, D-Prince William, who supports ending further reminders of the Confederacy, said the backlash by the Shenandoah board mirrors opposition to legislation she carried this session to repeal the state’s ability to issue special license plates honoring the Sons of Confederate Veterans and Gen. Robert E. Lee. The governor vetoed the measure last Friday.

“I think that this just underscores the importance of local elections and how people are reenergizing the sort of false story of the Civil War to try to hurt people and divide people,” Mundon King said. “They know that these names are divisive and hurtful.”

Sam Rasoul, chair of the Virginia House Education Committee, added that while this was a “stain” on the nation and the commonwealth, he still believes Virginia has made great progress.

“We are hoping that no other schools go backwards and build on this terrible decision that was made that will be an anomaly,” Rasoul said. “We need to keep moving forward and trying to find ways of embracing the values that truly make us American.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect that Shenandoah County’s population of Black students is 2.9%, not 29% as previously reported. It has also been updated to reflect that Martin Helsley refutes the remarks attributed to him in an Oct. 2019 school board candidates’ forum by The Northern Virginia Daily.

The post Virginia school board restores Confederate names appeared first on Virginia Mercury.