The Vietnam War: The Pictures That Moved Them Most

‘Who is the Enemy Here?’

The vietnam war Pictures That Moved Them Most

While the Vietnam War raged — roughly two decades’ worth of bloody and world-changing years — compelling images made their way out of the combat zones. On television screens and magazine pages around the world, photographs told a story of a fight that only got more confusing, more devastating, as it went on. As Jon Meacham describes in this week’s issue of TIME, the pictures from that period can help illuminate the “demons” of Vietnam.

And, in the decades since, the most striking of those images have retained their power. Think of the War in Vietnam and the image in your mind is likely one that was first captured on film, and then in the public imagination. How those photographs made history is underscored throughout the new documentary series The Vietnam War, from Ken Burns and Lynn Novick. The series features a wide range of war images, both famous and forgotten.

But few people have a better grasp on the role of photography in Vietnam than the photographers themselves, and those who lived and worked alongside them. With the war once again making headlines, TIME asked a number of those individuals to select an image from the period that they found particularly significant, and to explain why that photograph moved them the most.

Here, lightly edited, are their responses.

—Lily Rothman and Alice Gabriner

Don McCullin

Don McCullin— Contact Press Images

My picture of the U.S. corpsman carrying an injured child away from the battle in Hué is a rare occasion to show the true value of human kindness and the dignity of man. The child was found wandering the previous night between the North Vietnamese and the American firing lines. His parents had probably been killed.

They took the child into a bunker, cleaned him up and dressed his wounds under candlelight. These hard Marines suddenly became the most gentle, loving persons. It was almost a religious experience for me to record this extraordinary event.

The following morning, this corpsman took the child to the rear of the battle zone where he could be handed over for more medical attention. He carried the child as if it were his own, wrapped into a poncho, because it was quite cold. A naked limb is hanging from the poncho. Looking back today on this picture I took so long ago I can see that there is an echo here of the famous Robert Capa image of the woman whose head had been shaved at the end of WWII because she was considered to be a Nazi collaborator and had a child — whom she hugs to her chest — with a German soldier. I didn’t think of Capa when I pressed the shutter, but I believe both images share an emotional impact because they involve children. Though Capa’s illustrates cruelty, my corpsman illustrates humanity, almost saintliness — a man carrying a child away from the sorrow and injuries of war.

Howard Sochurek

Young guerrillas wear grenades at their belts, preparing to fight the encroaching Viet Minh forces in the Red River Delta, northern Vietnam, 1954. Howard Sochurek—The LIFE Picture Collection

Tania Sochurek, widow of photographer Howard Sochurek:

The conflict in Vietnam spanned almost 20 years. Howard was a staff photographer for LIFE in the early 1950s, when he was first assigned to cover the fighting in what was then Indochina. He was there on the ground for the brutal — and historic — fall of Dien Bien Phu that marked the end of the French involvement in the region.

It’s insane to think that these three young children with grenades were going off to fight the Viet Minh army. Sadly, they probably died quickly in the war. This is a photo that Howard felt was very powerful.

In 1954, Howard was again on assignment in Vietnam when he was called home to Milwaukee to be with his mother, who was terminally ill. The acclaimed photographer Robert Capa came in to take his place and cover the fighting. A short time later, Capa was killed by a land mine while out on a mission with the U.S. troops. Over the years, Howard would often tell this story and recall sadly that Capa had died covering his assignment. He was immensely proud to receive the Robert Capa Gold Medal Award for “superlative photography requiring exceptional courage and enterprise abroad” from the Overseas Press Club in 1955.

Gilles Caron

Gilles Caron —Fondation Gilles Caron

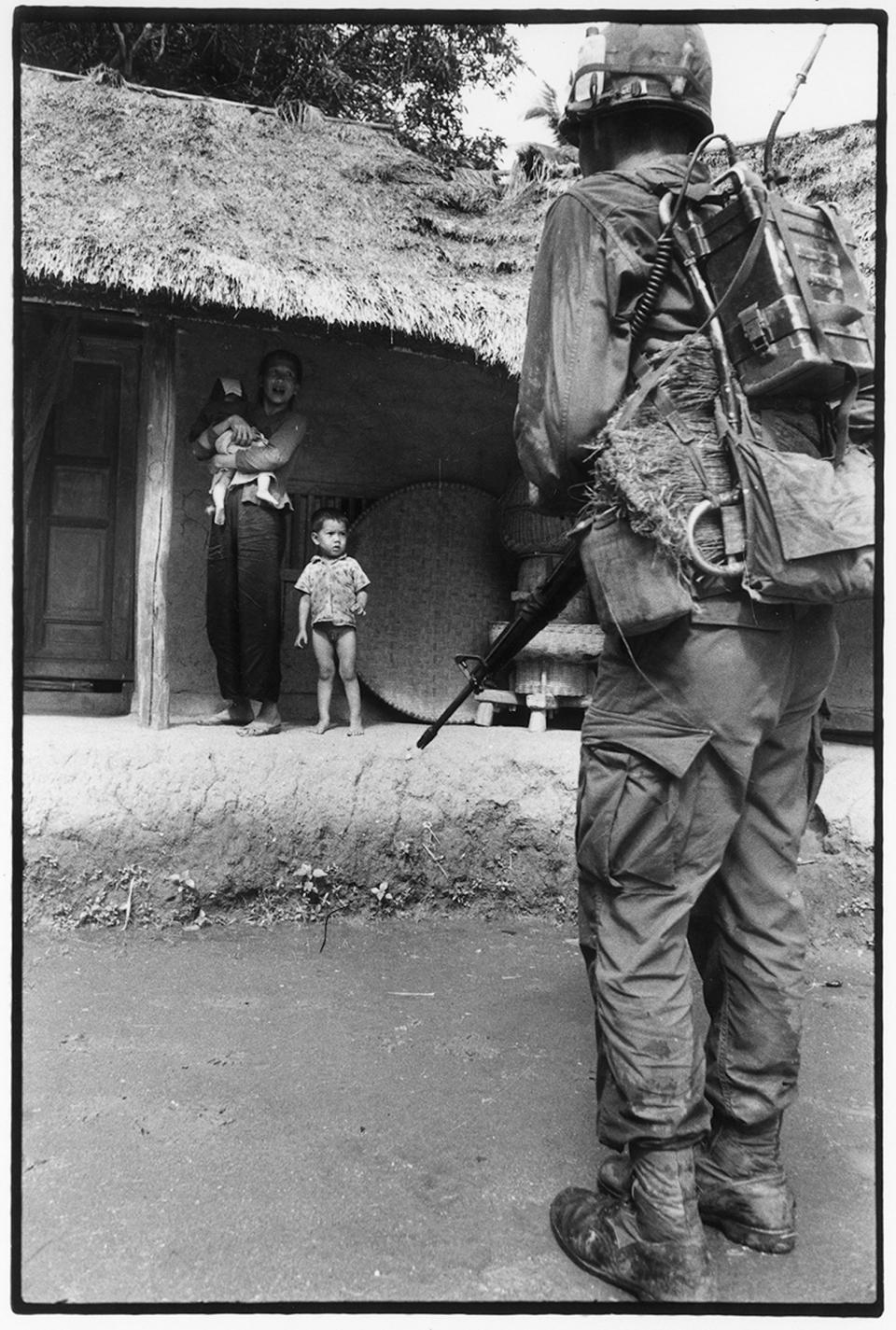

Robert Pledge, co-founder of Contact Press Images:

Who is the enemy here? The soldier, seen from the back, facing a Vietnamese woman hugging a baby, with a half-naked boy by her side? Or is it the young woman and her two children being confronted by an American GI? Are there not always two sides to a coin?

We are in a small hamlet near Dakto late in 1967, barely two months away from the Têt Offensive. The turning point of the five-year-old war, the offensive by elusive Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces failed in military terms but constituted a political victory in the arena of international public opinion. America was losing the war at home; David was defeating Goliath.

Gilles Caron’s atypical vertical image of a face-to-face encounter exposes deep cultural divide and distrust. Fear, tension and uncertainty are visible in the contained defiance of the mother and the awkward posture of the young warrior clutching his automatic rifle. Other locals and American military are nearby; the anxious glance of the child indicates as much. The contact sheets from that day reveal that the straw roofs would be set ablaze and the hamlet burnt down because of the suspicion that the villagers were harboring communist guerrilla forces by night.

In 1970, Caron would be captured by the Khmer Rouge, in neighboring Cambodia, never to be seen again. He had just turned 30.

Still images rarely give straightforward answers but they do offer illuminating clues for those who take the time to delve into them. Caron’s career in photography was very short — 1966 to 1970 — but his exceptional talent, intelligence, commitment and ubiquity leave us with an unmatched visual legacy.

Philip Jones Griffiths

Philip Jones Griffiths—Magnum Photos

Fenella Ferrato, daughter of photographer Philip Jones Griffiths:

Philip Jones Griffiths was born in a small town in the North of Wales in 1936, before the start of the Second World War. When American GIs landed on British shores they exuded generosity to their allies, giving away candy, nylons and cigarettes. I remember him telling the story of being lined up in the playground and being handed a Mars bar by a tall GI. He was instantly suspicious. A Mars bar was a very special thing indeed. Why were these uniformed men just giving them away?

This was Philip’s first glimpse into the efforts of an American army trying to win over “hearts and minds.” When he got to Vietnam he instantly recognized the same tactic being used there. This image perfectly shows the seductive and corrupting influence of consumerism on the innocent civilians of Vietnam.

Philip Jones Griffiths—Magnum Photos

Katherine Holden, daughter of photographer Philip Jones Griffiths:

This picture was taken by my father, Philip Jones Griffiths, in Vietnam in 1968 during the battle for Saigon. This is not a normal “war” photograph. It is not often you see “enemies” cradling each other. However, the American GIs often showed compassion toward the Viet Cong. This sprang from a soldierly admiration for their dedication and bravery — qualities difficult to discern in the average government soldier.

This particular Viet Cong had fought for three days with his intestines in a cooking bowl strapped onto his stomach. Francis Ford Coppola was so inspired by this image that he included a scene in his 1979 film Apocalypse Now with the famous line, “Any man brave enough to fight with his guts strapped on him can drink from my canteen any day.”

Henri Huet

Henri Huet—AP

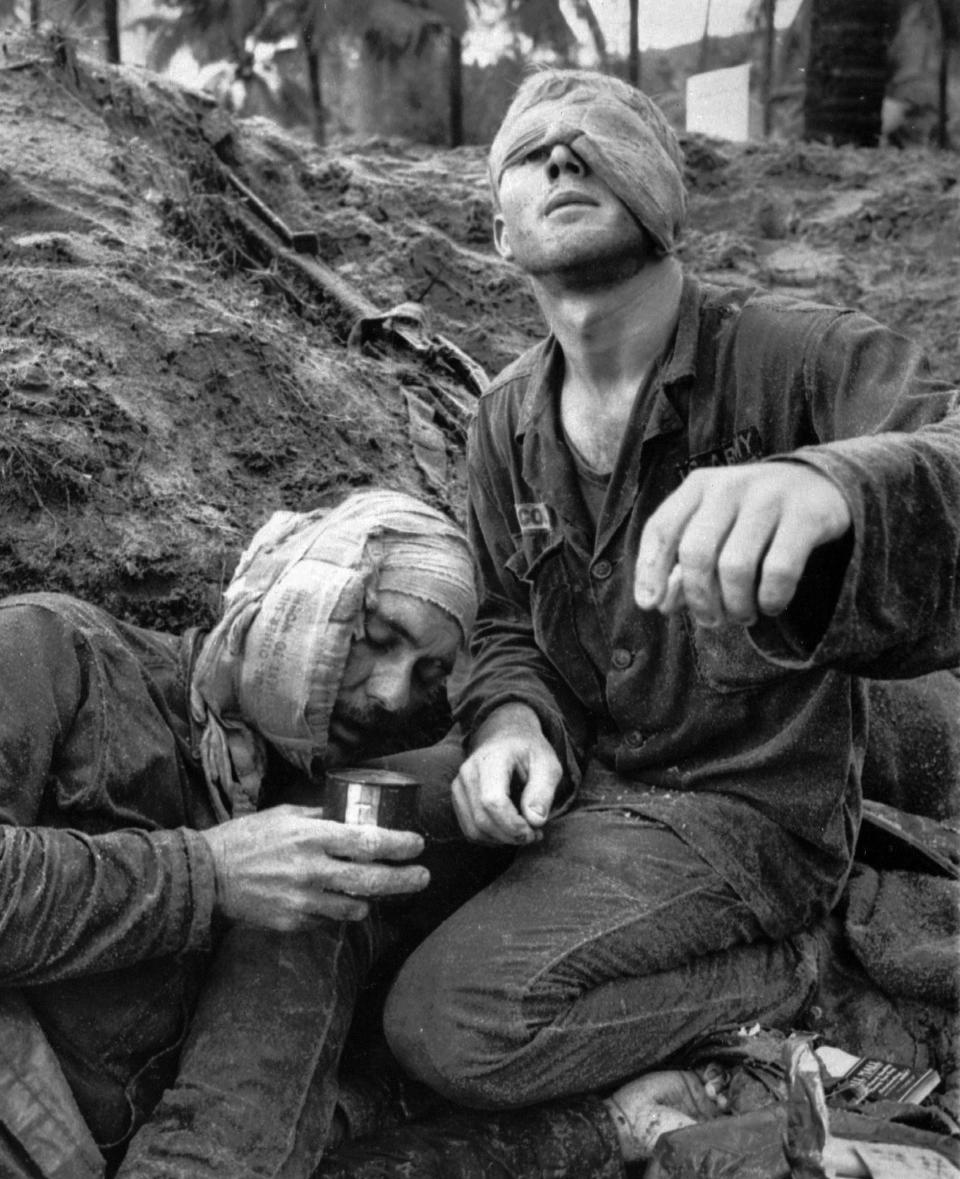

Hal Buell, former photography director at the Associated Press, who led their photo operations during the Vietnam War:

In all wars, the battlefield medic is often the stopgap between life and death. AP photographer Henri Huet, under heavy enemy fire, saw that role through his lens and captured the uncommon dedication that medic Thomas Cole displayed in this memorable photo. Cole, himself wounded, peered beneath his bandaged eye to treat the wounds of a fallen Marine. Despite his wounds, Cole continued to attend the injured in Vietnam’s central highlands in January, 1966. This photo was only one of several Huet made of Cole that were published on the cover and inside pages of LIFE magazine.

A year later Huet was seriously wounded and was treated by medics until evacuated. In 1971 Huet died in a helicopter shot down over Laos.

Tim Page

War Zone ‘C’ – Ambush of the 173rd Airborne, 1965. Tim Page

It was Larry Burrows who had to teach me how to load my first Leica M3; I got it as a perk having just had this image run as a vertical double truck in a 5-page spread in LIFE in the fall of ’65.

At the same time that Hello Dolly opened at Nha Trang airbase, a company of 173rd Airborne had walked into an ambush in Viet Cong base zone, known as the Iron Triangle. The sign had read “American who read this die.”

A class of prime youth shredded in seconds.

The dust-offs started coming within 30 minutes. I got a ride back to Ton San Nhut and was downtown in Room 401 of the Caravelle in another 30. Mostly, I remember carrying a badly wounded grunt whose leg came off and he almost bled out. The shot was made one-handed as we carried him out of the fire cone.

Dirck Halstead

Dirck Halstead—Getty Images

We rarely see images of Armies in full retreat.

Generally, the photographers who might have shot some of those images have long since bugged out, or have been captured or killed.

In mid-April of 1975, a small group of American journalists were invited to fly into the small provincial capital of Xuan Loc, South Vietnam, 35 miles north of Saigon, by commander Le Minh Dao. A siege by a massive North Vietnamese force was about to take place. The helicopter Dao sent to Saigon to pick us up deposited us just outside the town. Neither we, nor General Dao, had expected the tide of advancing communist forces to so quickly and completely surround the town.

General Dao, however, was full of vim and eager for the battle. Slapping a swagger stick along his leg, he quickly loaded the two journalists who had accepted his invitation, myself and UPI reporter Leon Daniel, into a Jeep and barreled into the town. At first, we thought it was deserted. Then slowly, and one by one, South Vietnamese troopers began to stick their heads out of foxholes they had dug in the streets. Dao yelled that they were prepared to fight the enemy, come what may. However, we noted with more than a little trepidation that none of them were budging from their holes as Dao led us down the dusty street. Suddenly, a mortar shell landed in the dust no more than 10 feet from us. It was followed by a barrage of incoming automatic weapon and artillery rounds.

Dao wisely called an end to his press tour. We tore back to a landing zone that we had arrived at less than an hour later. Dao called in a helicopter to evacuate us, but suddenly, the ARVN troops who had been seated alongside the road broke and ran for the incoming helos. In less time than it takes to tell, the panicked soldiers swarmed into the helicopter, which was to be our only way out. Crewmen tried to turn them back, but the helicopter lurched into the air with two soldiers hanging from the skids.

At that moment, Leon and I had a sinking feeling that we were going to be part of the fall of Xuan Loc. For us, the war looked like it was about to be over.

However, Dao had one more trick up his sleeve, and he called in his personal helicopter behind his headquarters. As we made a run for it, the General grabbed me by the arm, and said, “Tell your people that you have seen how the 18th division knows how to fight and die. Now go — and if you are invited back, don’t come!”

Joe Galloway

Joe Galloway—UPI/Getty Images

I snapped this photo at [the Battle of la Drang], LZ X-Ray, on Nov. 15, 1965. At the moment I hit the button I did not recognize the GI who was dashing across the clearing to load the body of a comrade aboard the waiting Huey helicopter.

Later I realized that I had shot a photo, in the heat of battle, of my childhood friend from the little town of Refugio, Texas. Vince Cantu and I went through school together right to graduation with the Refugio High School Class of 1959 — a total of 55 of us. The next time I saw Vince was on that terrible bloody ground in the la Drang. Each of us was terribly afraid that the other was going to be killed in the next minutes.

When my book about the war, We Were Soldiers Once…and Young, came out in 1992, Vince Cantu was driving a city bus in Houston. His bosses read the papers and discovered they had a real hero pushing one of their buses. So they made Vince a Supervisor and all he did from then to retirement was stand in the door with a clipboard checking buses in and out.

A story with a happy ending.

Larry Burrows

Larry Burrows —The Life Picture Collection

Russell Burrows, son of photographer Larry Burrows:

The fraction of a second captured in most photographs is just that: a snapshot of a moment in time. Sometimes, even in war, that moment can tell a whole story with clarity, but it can be ambiguous too.

The photograph that ran in LIFE in late October 1966 of Gunnery Sergeant Jeremiah Purdie, bleeding and bandaged, helped down a muddy hill by fellow marines, didn’t really need a caption. The written account around the photograph and a dozen others that brought Operation Prairie to LIFE’s readers told of infiltrating troops and of efforts to thwart them — of hills taken and given up. The detail not given was that Gunny Purdie’s commanding officer had just been killed on that hill, the radio operator “cut in half.” Neither did the article mention that the CO had called in artillery fire on his own position. Purdie was being restrained from turning back to aid his CO.

A few frames later, Larry Burrows took another photograph: Purdie is still being held back, but in front of him is another wounded man and Purdie’s arms are outstretched. The scene is as wretched as the other. Purdie, wounded for the third time in the war, was about to be flown to a hospital ship off the Vietnamese coast and leave that country for his last time. This photograph has come to be known as “Reaching Out.”

My father, Larry Burrows, selected that frame himself, but it wasn’t until more than four years later, after he was shot down and killed, that it was published for the first time. The composition of the photograph has been compared to the work of the old masters, but some see it more cinematically: as if you could run a film backwards and forwards to view more of the story. Exhibiting museums have found in it Christian iconography. And at least one psychiatrist treating war veterans has used it in his practice.

My father didn’t know that Jeremiah Purdie had enlisted in a segregated Marine Corps 18 years earlier, that cooking in the mess and polishing shoes were the limits placed on his service. He didn’t know that before Purdie’s persistence finally earned him a transfer to the infantry, he had taken courses at the Marine Corps Institute, confident that the transfer would come and he would be ready. Unknowable then was also the life Purdie would live after his 20 years in the Marine Corps, or how important to him faith would become.

At Jeremiah Purdie’s packed funeral, there wasn’t a man or a woman with a story to tell that didn’t mention how, in some way, he had reached out.

David Hume Kennerly

David Hume Kennerly

Long-forgotten photographs sometimes leap out at me and I am stunned by certain moments that I documented that were so routine when I made them, but are now infused with new emotion and meaning. This picture of a haunted-looking young American GI taking refuge under a poncho from monsoon rains in the jungles outside of Da Nang while on patrol in 1972 is one of them. The soldier’s eyes reveal, and you don’t need a caption to explain it, that he most likely experienced hell along the way.

During the time I spent with him and his platoon they didn’t come into direct contact with the enemy, but there was always a common undercurrent that ran through them, a palpable anxiety and fear about what could come their way in a split second. These men had seen buddies cut in half by shrapnel from an incoming round, or watched a friend’s head explode from a bullet between the eyes that earned him a one-way ticket home in a body bag. Many had that intense blaze of realization when a comrade was suddenly, violently, unexpectedly gone, and marveled at still being left intact. Some experienced a flash of guilt when in a starkly honest millisecond they thought, “Glad it was him, not me.” That big ugly candid moment was immediately pushed down, but it would creep back every now and then, especially back in the world when they gave a hug to their new child, the one their dead buddy would never have.

This image of the sheltering soldier is particularly compelling to me for what I don’t know. What was his next act, and what happened after he returned from Vietnam? The photo didn’t win any prizes, might not even been published, but as a flash forward it represents every soldier who returns from any war after the battles were history, guns silenced and the odds of getting killed beaten.

Paul Schutzer

Paul Schutzer—The Life Picture Collection/Getty Images

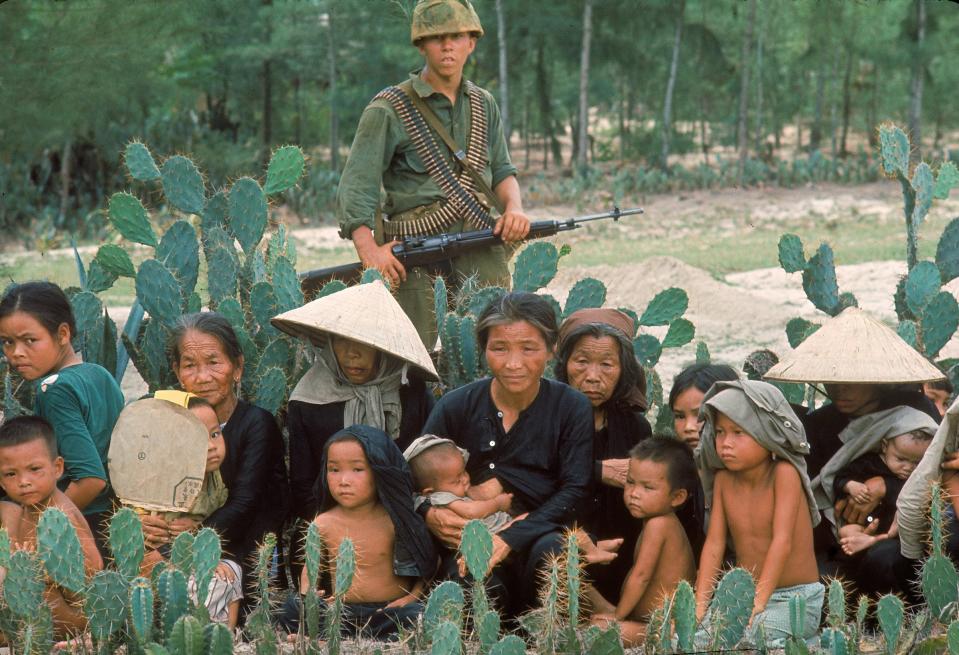

Bernice Schutzer Galef, widow of photographer Paul Schutzer:

Paul got carried away with all the emotions that happen in war, and he was right in there with the soldiers in battles. He saw everything; he saw the fatigue of the American soldiers, their fear, the prisoner’s fear. There was one photo of prisoners being guarded by an American soldier about 18 years old. The captives were young children and old women and one woman is nursing her baby. Unfortunately the young soldier was later killed but this image conveyed the senselessness and horror of how the human condition was playing out. The soldiers were very sympathetic to the civilians and one medic befriended them. The last photo in the photo essay shows the medic and a child walking away together, holding hands, and the child’s head is burned from napalm. It was the first time that Americans saw and learned that we were using napalm. Paul received many letters saying “thank you for what you showed us.”

David Burnett

David Burnett—Contact Press Images

In the days before “embeds” — this generation’s enforced melding of photographer and military unit — there was a certain sense of freedom we owned as photographers, being able to go directly to where the story was. In Vietnam in the early 1970s, the only real limitation was finding a ride. But nearly until the end of the U.S. war, if a helicopter or truck had a seat available, they would take you along.

We would often “embed” ourselves with a platoon or squad, but it was more of a gentleman’s agreement than any kind of official policy, based in the main on the idea that we, the photographers, were there to tell their story, and they, the soldiers, realized that unlike them, we didn’t have to be there. It was by choice. It created a sense of mutual respect that in many ways is challenged by the new “embed” ethos. That said, it was often a world of anonymous photographers spending time with anonymous soldiers. So while we would talk with the troops about what was happening that day, there were many moments where in the course of making photographs, I would just keep moving along. I usually knew the unit but looking back now, so much I wish I had noted was simply never written down. It was forever a search for a picture, and you never knew, sometimes for weeks, whether you had that picture or not. My film had to make it all the way to New York before it could be processed and edited.

One morning near the end of the unsuccessful Laos invasion of early 1971 (an attempt to cut the Ho Chi Minh trail), I wandered into a group of young soldiers who were tasked with fixing tanks and track vehicles which were regularly being rocketed by North Vietnamese troops just down the road. This soldier and I exchanged pleasantries the way you would in the dusty heat. He went back to work after reading a letter from home, and I moved on to another unit. But for that fraction of a second, in his face, his posture, was all the fatigue and despair of a young soldier who is surely wondering what in the hell he’s doing there, so far from home.

Catherine Leroy

Catherine Leroy—Dotation Catherine Leroy

Fred Ritchin, Dean Emeritus of the School at ICP:

There is something both surreal and strikingly sad in this photograph by Catherine Leroy. An empty helmet — is its owner still alive? — is shown front and center, resting on the ground in the soft gray light like a discarded soup bowl or a cleaved skull. It is photographed as if forming the center of a broken compass, one without arms, pointing nowhere. In the fairly rendered background a soldier, probably wounded, is seen surrounded by comrades who, somehow, form an awkward Pietà. The violent spectacle has temporarily receded, and the reader, in this previously unpublished photograph, is given its remains, both the sacred and the partly absurd.

Leroy went from France to Vietnam in 1966 at the age of 21, with a single camera, no assignments and $150 in her pocket; she would stay until 1968. She managed to get accredited by the Associated Press, covered numerous battles, was seriously wounded by shrapnel that would remain in her body, parachuted into combat (small and thin, she was weighed down so as not to be blown away), was taken prisoner by the North Vietnamese (which she used as an opportunity to produce a cover story for LIFE Magazine), and remained obsessed by the war until her death in 2006.

Consumed by a ferocious anger at the hypocrisies of politics at various levels, in her last years Leroy created a website and then a book, Under Fire: Great Photographers and Writers in Vietnam, paying homage to her colleagues 40 years after the war had ended.

Sal Veder

Released prisoner of war Lt. Col. Robert L. Stirm is greeted by his family at Travis Air Force Base in Fairfield, Calif. Sal Veder—AP

I had photographed POWs returning home time and again, and been in Vietnam on two tours myself, as a photographer. On that day, There were 30 or 40 photographers boarded on a flat-bed, including TV. I was photographing a different family and out of the corner of my eye saw the action and turned. I was lucky to get a break. It was a great moment for Americans! The joyousness of the reunion and the coming together of the family as a visual is outstanding because it was the end of the war. We were glad to get it over with. I’m thankful that this is my picture. I feel it’s symbolic, but I’m conflicted about it, knowing what I know. The picture is there and it comes back up again. There is no way to avoid it.

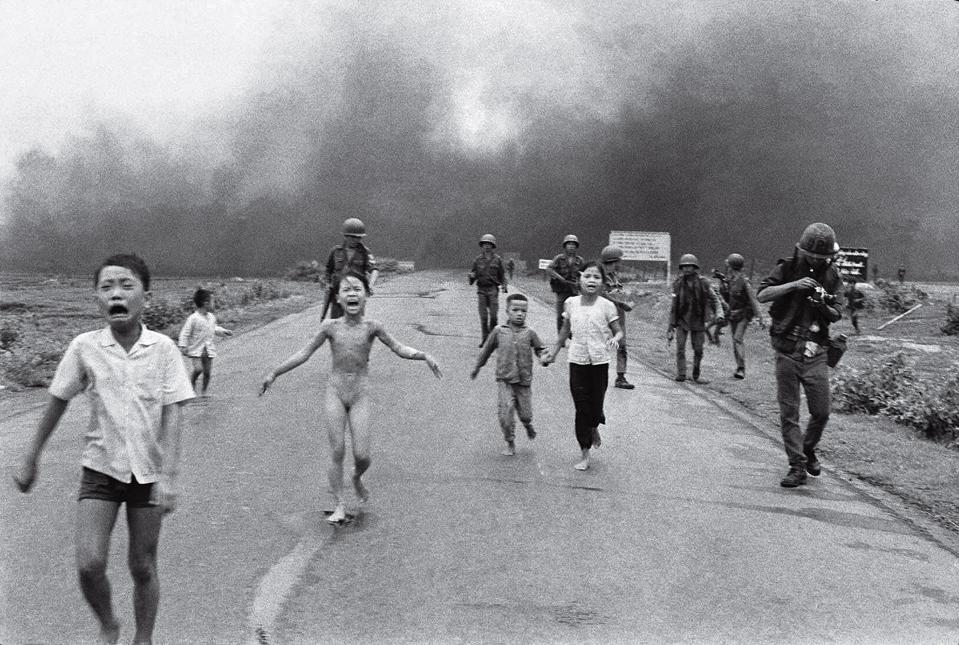

Nick UT

Nick UT—AP

My older brother Huynh Thanh My, who was killed covering the Vietnam War for the Associated Press, always told me that an image could stop the war and that was his goal. I was devastated when he died. I was very young. But there and then, I decided to follow in his footsteps and complete his mission. A few years later on that fateful day in 1972 on the Trang Bang road, my brother’s goal was accomplished. No one was expecting people to come out of the bombed-out burning buildings, but when they did, I was ready with my Leica camera and I feel my brother guided me to capture that image. The rest is history.

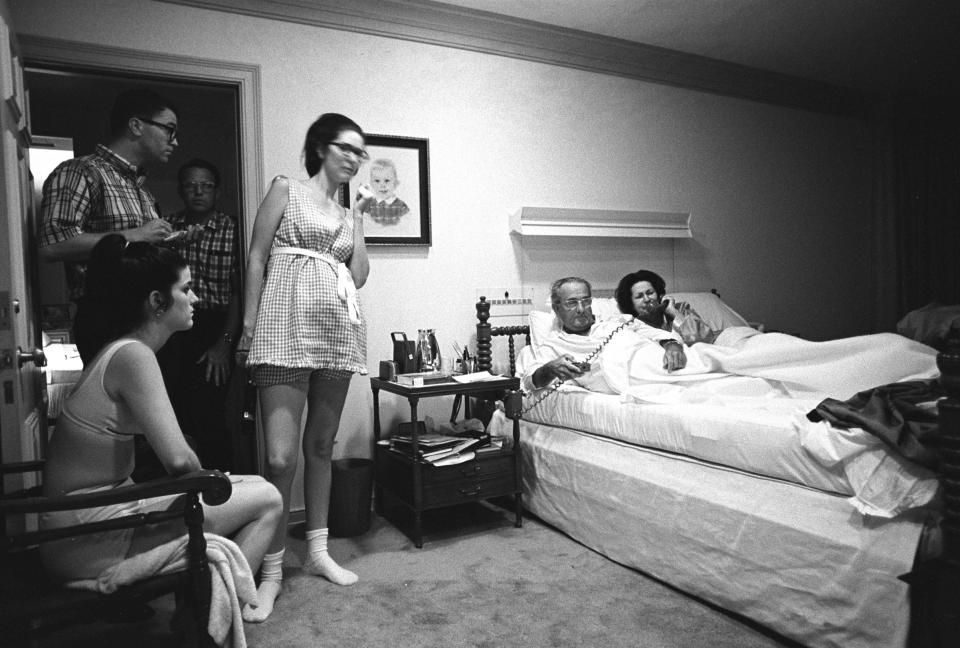

Yoichi Okamoto

As tens of thousands of anti-war protestors rioted in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention, President Johnson and his family watched from the bedroom at his ranch in Stonewall, Texas. Yoichi Okamoto—LBJ Library

Pete Souza, former White House photographer for Presidents Reagan and Obama:

This is truly an incredibly intimate picture. The caption provides pertinent information about the circumstance: the who, what and where. But I’m fascinated by the photograph because of the man behind the camera: Yoichi Okamoto. The first civilian hired as Chief White House Photographer, Okamoto also became the first one to truly document the Presidency for history. It’s obvious looking at this photograph that he had unfettered access to LBJ and that everyone was comfortable with him being in the room — even when the room was the President’s bedroom.

Raymond Depardon

Richard Nixon campaigns in Sioux City, Iowa, October 1986. Raymond Depardon—Magnum

(Translated from the French)

After I photographed the Democratic Convention in Chicago, which was very turbulent and contested, I wanted to photograph the future President. I worked for a little cooperative French agency, Gamma, which we had created a few years earlier. I arrived from Miami on the press plane that accompanied the candidate. We were positioned at a little airport in Sioux City. It was the morning. It was windy. Nixon left the plane.

I almost did not make the photo — the man with the flag and Nixon on top of the aircraft stairs. It was too much.

Art Greenspon

Art Greenspon—AP

Excerpted from a 2013 interview with Art Greenspon by Peter van Agtmael, a Magnum photographer who has covered the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan:

“As the first medevac chopper hovered overhead I saw the First Sergeant with his arms in the air. I saw the medic shouldering wounded and then I saw the kid on his back in the grass. I have got to get all this in one picture, I thought. My heart was pounding. Was 1/60 fast enough? Screw it. Shoot pictures. I got three frames off, and the moment was gone.

I knew what was in the camera, but when I went to wind back the film, I couldn’t. The film in my Nikon had become stuck to the pressure plate from all the moisture. My Leica was soaked, too, and I wasn’t sure what kind of pictures it was producing.

The weather closed in again. I had given all of my food away so I didn’t eat for two days. I wrapped my cameras in a damp towel and put them in my pack. I guarded that pack like a mother hen.

I flew out with the second chopper loaded with body bags. A kid headed out for R&R and a floor stacked with KIAs [killed in action]. War sucks.”

Alice Gabriner, who edited this photo essay, is TIME’s International Photo Editor.

Lily Rothman is the History and Archives Editor for TIME.