Veteran writer Howell Raines unearths story of Alabama Unionists | DON NOBLE

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

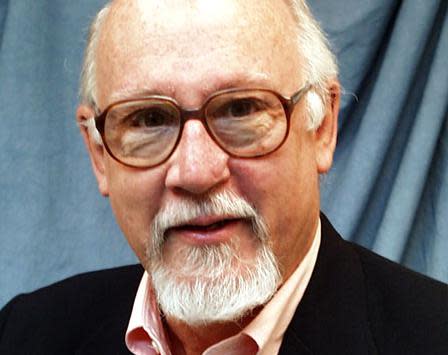

Alabama writer Howell Raines, now retired from his job as executive editor of the New York Times, has been able to bear down and finish a project of many years that is dear to his heart: “Silent Cavalry: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta — And Then Got Written Out of History”.

Though born and raised in Birmingham, Raines’ roots go back for generations to Winston County. His first book, the novel “Whiskey Man,” is set there and in its fictional way sets up the contrast between Alabama north of Birmingham-Tuscaloosa and the Alabama of the Black Belt.

More: Story collection offers 'grit lit' with tough female characters | DON NOBLE

There were, he says “two white Souths.” The differences are many. Appalachian Alabama is hilly, the Black Belt flat with rich soil suitable for cotton plantations and, therefore, for slavery. Winston County produced only 352 of the 1 million bales grown in Alabama in 1860 and accounted for 122 of the state’s 435,080 slaves.

As secession loomed in the late 1850s, it was clear that north Alabama was not interested. One state referendum vote passed by an unimpressive 61 to 39.

The mythology of the "Lost Cause" began to form immediately.

The first falsehood was: Alabama opinion coalesced after the vote. Jeffersonian Democrats became Rebels. Not so.

This myth could thrive only until 1862, when the Confederate draft was instituted.

Unionists refused service, “laid out” in the woods or caves, and Gov. John Gill Shorter sent troops to catch the draft-dodgers, arrest them, even execute them for treason against the treasonous government in Montgomery. From that point forward, a bloody civil war raged in in North Alabama.

Hundreds left to join the Union Army, and Alabama politicians and historians, then and afterward, strongly preferred that no one ever know about this.

Raines’ latest book is a detailed history of one band, the First Cavalry Regiment of Alabama, U.S.A.

He has searched for decades and found surely almost all there is to know. Most of this regiment came from the Free State of Winston, named, unofficially, in response to Chris Sheats’ speech in Looney’s Tavern.

The unit fought as spies, as reconnaissance outfit and as personal escort to Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman and fought bravely as the Union Army burned Atlanta and marched through Georgia to the sea. Famously, Sherman said, "I can make this march, and make Georgia howl."

The Confederate Army, Sherman surmised, would not surrender until the Southern citizenry, exhausted in fighting for slaves most did not have, demanded it. Sherman’s campaign of destruction had an aim. Raines writes, "If Southerners wanted to preserve their property, every white person, gentry and common folk alike, must end their support for an army in rebellion."

As savage as this campaign in Georgia was, Sherman had a fairly 18th-century view of warfare, with rules. When his troops came upon a road mined with "torpedoes" — what we now call land mines — and an officer lost his leg, Sherman was outraged. "This was not war, but murder." What happened next underscored the depth of animosity between armies by that point.

Sherman ordered that Confederate prisoners of war be brought forward to walk down the mined road, to either explode the torpedoes or dig them up.

After the fighting ended, Raines writes, a war of propaganda, pride and mythology raged on. The Confederacy was touted not as a defense of slavery but as “a tragic story of undeserved suffering inflicted on a noble, if misguided, class of Southern aristocrats on their plantations and the dashing knights of the Rebel army.”

The bravery, the exploits even the existence of Southern Unionists was ignored, and the "Lost Cause" was promoted by academic historians and patriotic Alabama state archivists like Marie Bankhead Owen. He writes "It was a 'civil religion' manufactured and codified during the Gilded Age by revanchist thinkers."

Sherman had written, "The young bloods of the South: sons of planters, lawyers about towns, good billiard-players and sportsmen, men who never did work and never will. War suits them, and the rascals are brave, fine riders, bold to rashness .... they are the most dangerous set of men that this war has turned loose upon the world. They are splendid riders, first-rate shots, and utterly reckless ... These men must all be killed or employed by us before we can hope for peace."

Raines suggests that the descendants of these men are still with us. "The sleek, gentrified downtown Tuscaloosa of today features a "strip" of Vegas-like clubs, and the University of Alabama's central quadrangle is surrounded by high-rise condominiums where fashionably dressed students frolic courtesy of their parents' money."

Raines’ anger at Alabama classism — the arrogant cultural superiority of the planter class over the yeomen, the assertion that his people were hillbillies, utterly uncultured — is just as great as his anger over slavery and racism; and that is saying something.

Don Noble’s newest book is Alabama Noir, a collection of original stories by Winston Groom, Ace Atkins, Carolyn Haines, Brad Watson, and eleven other Alabama authors.

“Silent Cavalry: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta — And Then Got Written Out of History”

Author: Howell Raines

Publisher: Crown Publishing

Pages: 541

Price: $36 (Hardcover)

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: Howell Raines unearths story of Alabama Unionists | DON NOBLE