'It's very tough': UT Medical Center frontline workers endure the pandemic and prep for a new wave

When Bailey Baker started working as a nurse in the medical intensive care unit of the University of Tennessee Medical Center three years ago, she thought she would be working with a variety of patients.

"You're dealing with everything," Baker said. "One day you could come in and have three patients there for completely different reasons. It just facilitates learning and facilitates all of those things, and I like for my brain to be continuously learning."

The ICU used to be unpredictable, and Baker liked the challenge. But she worries that things will never go back to the way they were before the coronavirus pandemic.

"You know, every second of every day, just things feel like they're never going to be normal," Baker said. "Especially being in a COVID unit, like, almost all of our patients are positive all the time. To have a negative patient, it's like, 'Oh, this is a break.'"

UT Medical Center administrators completely transformed the operation when the coronavirus pandemic took hold in the United States in March 2020. Since then, the hospital has endured COVID-19 spikes and slowdowns, and hospital staffers have experienced a rollercoaster of emotional, mental and physical stresses.

Now they're worried about how they'll handle the next wave. There are signs that it is coming.

ONE AND 100: One pandemic, 100 stories of its impact on the South

The delta variant crashed through Knox County late this summer, and then daily new cases fell down to an average of below 50 cases per day in early November. This roughly coincided with the lowest number of COVID-19 patients in the 11-county Knoxville Hospital District with only 127 patients. For the sake of comparison, at the height of the delta wave, over 700 people were hospitalized district-wide, with 173 hospitalized at UT Medical Center alone.

Cases and hospitalizations have once again started to creep upward but not with the same ferocity. Right now there are about 200 people hospitalized district-wide for COVID-19, with only about 30 at UT Medical Center.

It is not clear what these trends will hold since the omicron variant was only detected in Knox County on Dec. 17. But the variant combined with the after-effects of Christmas and New Year’s gatherings could easily trigger another surge.

"It's just caused a lot of burnout, and that is sad because I love my job, and I'm really ready for things to be normal so that I can go back to loving my job," Baker said.

Working through long, repetitive days

A typical day in the ICU is pretty rough for Dr. Paul Branca, an associate professor of medicine and the medical director for the medical ICU, and his team.

"This pandemic is the perfect storm for a pulmonary critical care person because, even when it's mild or moderate, COVID is affecting the lungs," Branca said. "So we see a lot of folks who never thought they'd need to see a lung doctor."

Branca is usually at the hospital by 7 a.m. after checking on patients virtually and learning about any issues that developed overnight. He's there until 5 p.m., treating patients, speaking with families over the phone and coordinating which patients are in the ICU and who is taking care of them.

"A bit of (my job) is playing traffic cop: trying to make sure that only the sickest folks are in the ICU, trying to coordinate care across the spectrum so that it's focused better," Branca said. "We're dealing with not just COVID, of course, we're dealing with all the same ICU folks that we've ever dealt with, and add to that the COVID folks."

Days at the hospital are long and repetitive for nurses and respiratory therapists, too. Baker says she is lucky to clock out by 7:30 p.m. after being there since 6:30 in the morning.

ONE AND 100: Kasey Beem, ICU nurse at the University of Tennessee Medical Center in Knoxville

Before the pandemic, Baker would be ready to leave as her shift ended and waited by the time clock to punch out at the exact time to be responsible with her hours. But small changes in her day have added up.

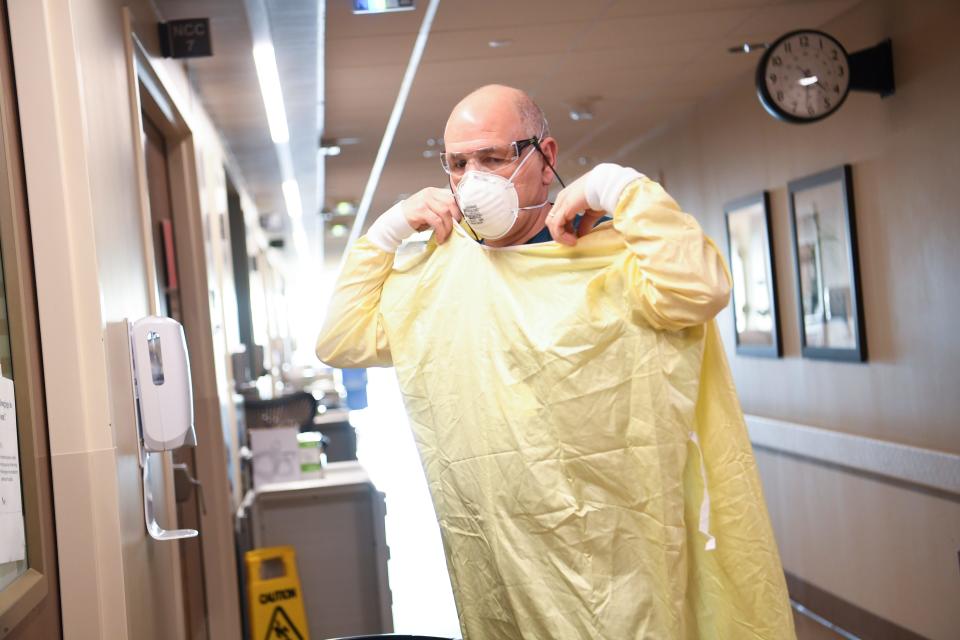

"Like, 50 to 100 times a day, you're going into a patient's room, and every time you do that, it's like three to five minutes of getting your mask on or getting your face shield on, and getting your gown on, and your gloves, and just double-checking that you're doing what you need to do to protect yourself and your family going home," Baker said. "That adds up, and that's time we used to be charting or providing direct patient care or talking to family members. ... We didn't really get any more time in our day."

Ashley Branson, a respiratory therapist, says that there were points where team members were working far beyond their scheduled hours.

"It's very tough," Branson said. "I've done a couple of rotations where we've been so short-staffed that we were kind of doing shifts and a half there at one period because night shift struggling so bad with staffing. So some of the day shift therapists would stay until the midnight shift."

But the work doesn't stop at midnight, according to Brittany Steele, a nightshift nurse on the progressive care unit.

"With these COVID patients, you find yourself in these rooms sometimes for hours," Steele said. "It is very time-consuming with these patients."

Confronting unique hardships

One of the biggest challenges for the ICU team has been upholding the new visitation policy. At the beginning of the pandemic, UT Medical Center limited visitation to minimize the spread of the virus.

Before the pandemic, family members used to be able to visit patients in the ICU at any time. Baker said that helped build trust with nurses because family members would witness the round-the-clock care they provided.

"They were able to build confidence in what we were doing for their family member, and now we don't get to establish that," Baker said.

It's harder to establish that trust through phone calls and FaceTime.

"A lot of times, I will just set the FaceTime up while I'm providing patient care, you know, that way they are seeing that I'm giving my medications and their family members are in good hands," Baker said.

ONE AND 100: Dr. Chris Klenck, college football team physician

"You think that that would make my life easier, but it doesn't. It makes our lives so much harder because you have these worried family members who can't see these extremely sick people that may care a lot about. Not being able to see their loved ones obviously stresses them out and so they're calling multiple times a day."

And more of the UT Medical Center's patients are young, which has been an emotional challenge for many young health care professionals.

"People think that COVID is hitting our elderly generation, but it's not," Brittany Steele, a nurse on the progressive care unit. "It's affecting our young generation, you know, 20-year-olds, and ... it definitely is mentally and physically exhausting."

Medical students went from initially being protected from the dangers of COVID to being thrown into the center of it a year later.

"We're seeing a lot of folks in the age range where med students and residents are starting to really identify with (the patients)," Branca said. "We're seeing our younger nurses identify with, for example, pregnant patients with COVID."

And then getting pregnant patients the care they need has been a challenge in itself, according to Dr. Kim Fortner, vice president of the center for women and infants at UT Medical Center.

"One of the other things that we're seeing is just pregnant women coming in so scared and feeling like going to the ICU is equated with, 'You're not doing well, we're not expecting you to do well,'" Fortner said.

Fortner tries to remind these hesitant future parents that the ICU often has more resources and care teams than her office.

"We've been able to, you know, talk through those issues and help people understand that it's not always about your own clinical condition," Fortner said. "It is often more a reflection of how can we best meet your needs best take care of you."

Preserving support systems

Health care professionals have been supporting patients nonstop throughout the pandemic. But who has been supporting them?

Several nurse managers and other administrative staff have stepped up.

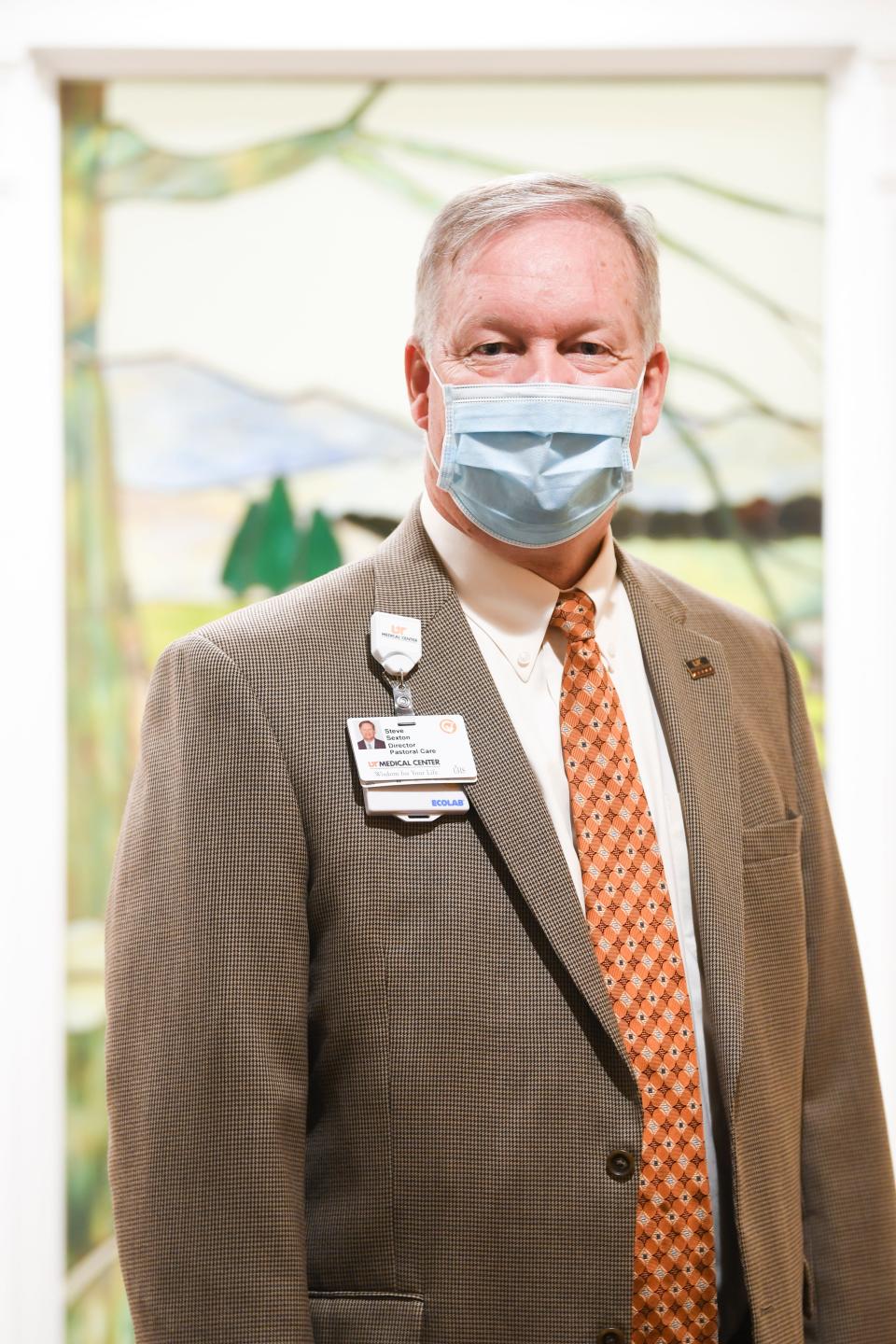

Steve Sexton, the director of pastoral care at the hospital, mentioned how his team not only checks in with patients and families now also with staffers. They check in with hospital staff before their rounds or in between shifts to see how they're doing and provide space for them to talk about how they're coping.

"Most people may not be aware (that) we spend as much or more time with staff to provide spiritual, emotional support," Sexton said.

"(We've) just been more intentional about paying attention to staff and how they're doing and rounding more frequently or with more purpose on COVID floors," Sexton said.

In the face of challenges, though, there have been innovations across the hospital.

ONE AND 100: Britton Patterson, Knoxville public works employee

"We've truly made sure that this is a multidisciplinary effort," Branca said. "You know, I just have to hand it to the other folks that are doing stuff because as much as I coordinate, they actually work. ... They are truly hands-on and doing the kinds of things that people can't even imagine."

Not everyone survives COVID-19. Knox County has lost about 1,000 people to the disease. But seeing patients improve from where they started gives the team hope.

"When you have success stories and you're able to get somebody off the ventilator successfully, it's all hands on deck because it's just like a big cheerleading squad in the patient's room or outside the door," Branson said. "We're all just very thankful because it seems like that's very far few and far between."

But even after people leave the hospital, the battle isn't over.

"Post-COVID is going to be a little rough," Branca said. "And not just the post-COVID syndrome, there's going to be a lot of people that are going to have lingering effects. And so I don't think we'll get back to a truly normal medical system for a while for years."

Until things do get back to "normal," health care professionals are just asking for grace.

"Be patient with your health care workers," Branson said. "We're doing the best that we can. We're all working in short-staffed and, you know, work in very vigorous hours trying to do the best we can, taking care of your loved ones."

Knox News Science, Technology and Culture reporter Vincent Gabrielle contributed to this story.

Becca Wright: Higher education reporter at Knox News

Instagram | Twitter | Email | 865-466-3731

Enjoy exclusive content and premium perks while supporting strong local journalism. To get started, visit knoxnews.com/subscribe.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: How UT Medical Center staff are coping after two years of COVID-19