Venice’s tourist tax scheme has ‘resoundingly failed’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Venice’s efforts to reduce the number of daytrippers by introducing an entrance fee have “resoundingly failed”, campaigners have claimed.

Critics said not only had the number of tourists not dropped since the fee was launched last month, it had actually increased and the only solution to the overtourism problem was to cap visitor numbers.

“On Sunday, we had 70,000 visitors, compared with 65,000 on an equivalent day in the same period last year,” said Giovanni Andrea Martini, a centre-Left city councillor who sits in opposition to Venice’s centre-Right mayor, Luigi Brugnaro, the architect of the entrance charge.

“This was a measure that was heralded as a way of reducing tourist arrivals but it has resoundingly failed,” he said.

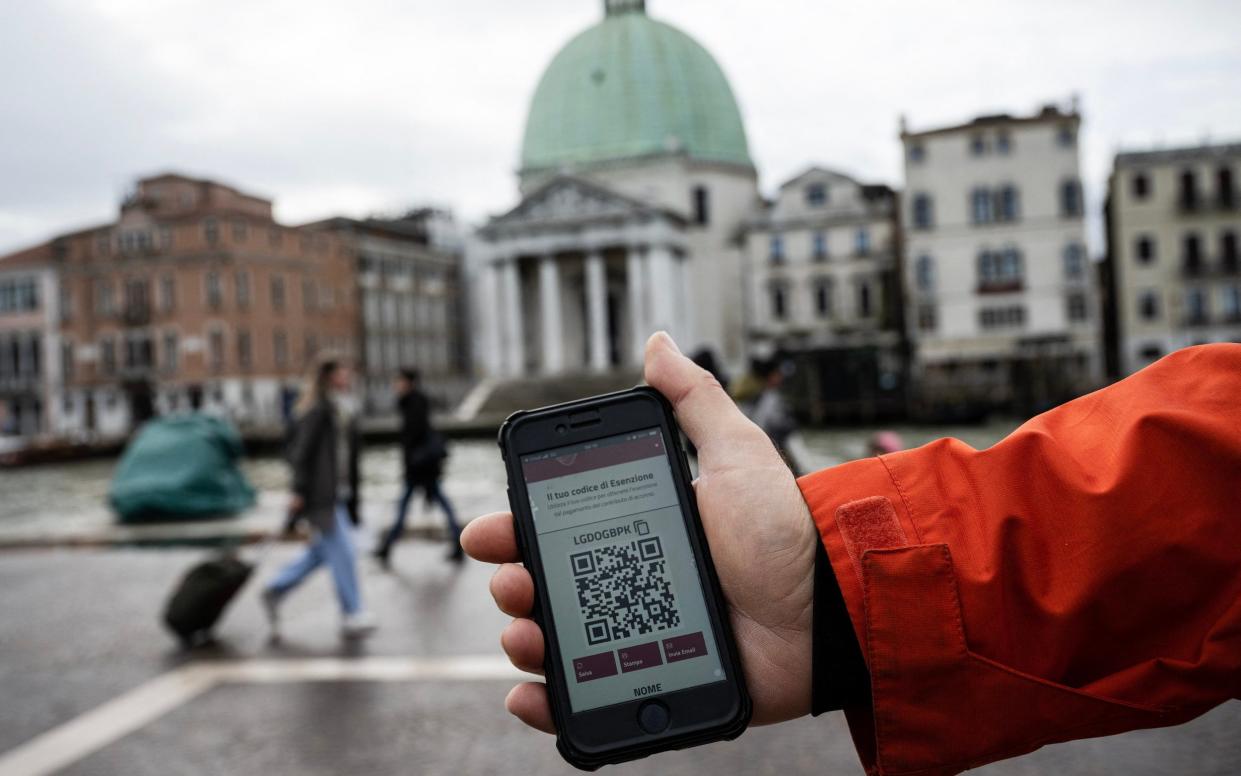

The entrance payment, a world first, was launched at the end of April and will apply to 29 days between then and mid-July.

Visitors who spend at least one night in the city are exempt but they must register online before they arrive.

“The numbers show that the ticket has not in any way reduced the influx of tourists. In fact, the numbers are higher than last year,” said Mr Martini.

“It is useless and damaging. It has not saved the soul of the city. Venice has been treated as the goose that lays the golden eggs. Private business interests have been placed above the interests of inhabitants.”

A survey by an organisation called Fondazione ICU showed that 89 per cent of Venetians in the historic centre were against the entrance payment, he said.

Speaking at a press conference in Rome, campaigners argued that the entrance fee was flawed because there were too many exemptions.

For instance, it does not apply to the 4.6 million people who live in Veneto, the region around Venice – they are still free to come and go as they like and make up a large share of the daytrippers whom the city wants to discourage.

The only way to tackle the problem of overtourism in the short term was to introduce a cap on arrivals, the campaigners said.

No more than 50,000 visitors would be allowed to enter the city each day – instead of the average 80,000 who arrive currently.

In the long term, they said the focus should be on increasing Venice’s population. In the 1950s, there were about 140,000 inhabitants but that has now dropped to 49,000.

The city needs to diverge away from tourism, create new business ventures and provide more low-cost public housing for locals.

“Venice suffers from social desertification. There are whole districts that have been emptied of Venetians. If this trend continues then it is a mathematical certainty that the city will die. We need to bring them back to restore the social fabric. A living city is the only way to stem the advance of mass tourism,” said Mr Martini.

The number of short-term rental apartments should be drastically reduced, the critics said. New zoning laws should be introduced to limit the number of Airbnb apartments and the owners of the properties should be made to pay much higher taxes.

“We need to regulate the number of tourist apartments,” said Franco Migliorini, an expert on the effect of mass tourism on Venice. The city simply could not handle 30 million visitors a year, he said.

They also criticised the entrance fee scheme as a gross invasion of privacy. Tourists who stay at least one night in Venice are exempt from the payment but must register on a database, give their personal details and specify exactly where they are staying.

Even Venetians are subject to the system – if they want to invite friends from elsewhere in Italy to stay, they must go through a complicated procedure specifying names, addresses, numbers of guests and dates.

“Despite being a Venetian citizen, I have to ask permission to invite friends, as though I was a subject appealing to my sovereign,” said Enrico Tonolo, a lawyer and the president of a campaign group called Tutta La Citta Insieme or The Whole City Together.

He said information that was gathered from Venetians and tourists alike was kept on a database for up to five years. “It could be used as a system of surveillance,” he said. “It is without precedent for any city in the world.”

Venice council says the entrance fee is a work in progress that may need to be tweaked. It will review the results of the project in July.

“The first few days have shown that the system has worked better than expected in terms of organisation and checks. It is a long-term project and it would be wrong to think that all the problems linked to overtourism can be solved in 15 days,” a spokesman for the council told The Telegraph.

Luigi Brugnaro, the mayor, said: “The majority of people have understood that we want to protect the city. It is a measure that can be corrected or improved if necessary. No one is pretending that it is not difficult, but we are trying to find solutions.”