Utah, the youngest state, is getting older. Here’s why that matters

Utah has long been known as the youngest state, but declining fertility rates and an aging adult population means the state is getting older. (Getty Images)

Utah has long been known as the youngest state (with a median age of 32, according to the U.S. Census Bureau), but declining fertility rates and an aging adult population means the state is getting older.

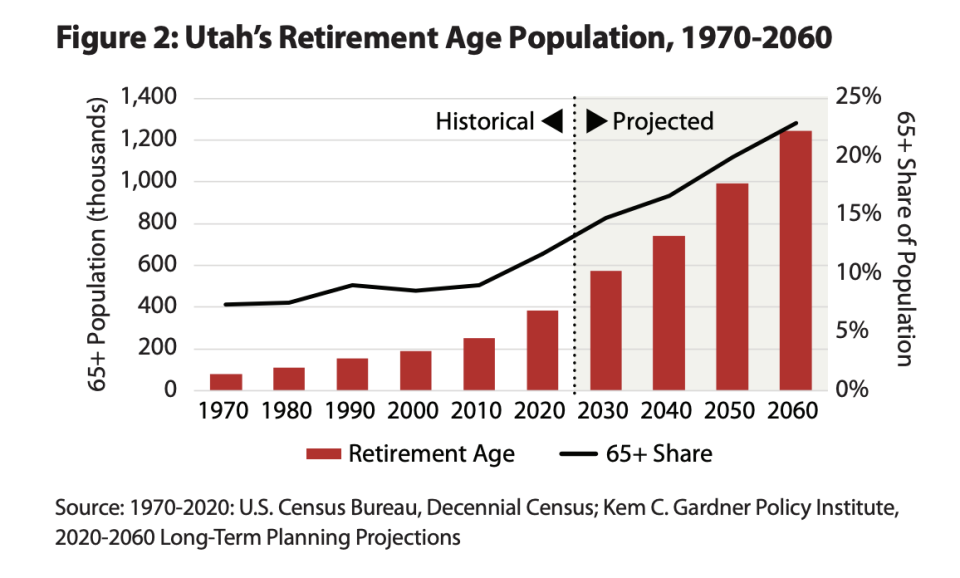

A new report released Monday by the University of Utah’s Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute shows Utah’s retirement-age population is on track to make up more than 20% of the state’s population by the year 2060.

It’s part of a growing trend that could have wide ranging impacts on many different areas of Utah life, from the housing market to the state’s labor workforce.

“In 1980, less than 8% of Utah residents were over 65, but by 2020, this share increased to nearly 12%,” said Mallory Bateman, director of demographic research at the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute. “Our projections indicate this trend will continue, and the current data shows that different stages of life relate to outcomes in education, economics, housing, and health.”

Bateman told Utah News Dispatch in an interview Monday that Utah’s changing demographics is an issue that Utahns and policymakers will need to come to terms with in coming decades.

“We are the youngest state in the nation, (so) we’ve really focused a lot of our attention on that youth population. But I think we haven’t really grappled with an aging population in a way that we probably will in the future.”

So Bateman said she hopes the data will help inform policymakers and others as they make decisions about what Utah’s future will hold, and “start thinking about the whole life span in their planning, and considerations for community needs.”

Housing

The report notes that as Utahns age “they become more likely to own their homes,” with homeownership rates increasing from nearly 19% for Utahns that fall into the 15 to 24 age group to 86.4% for the 65 to 75 age group.

However, homeownership rates decline slightly in the 75 to 84 and 85 and older age groups, the report notes, as more Utahns move out of their homes and into rental units, which includes some retirement and assisted living communities.

Additionally, as Utahns age, their ability to pay for their housing can change and become more difficult.

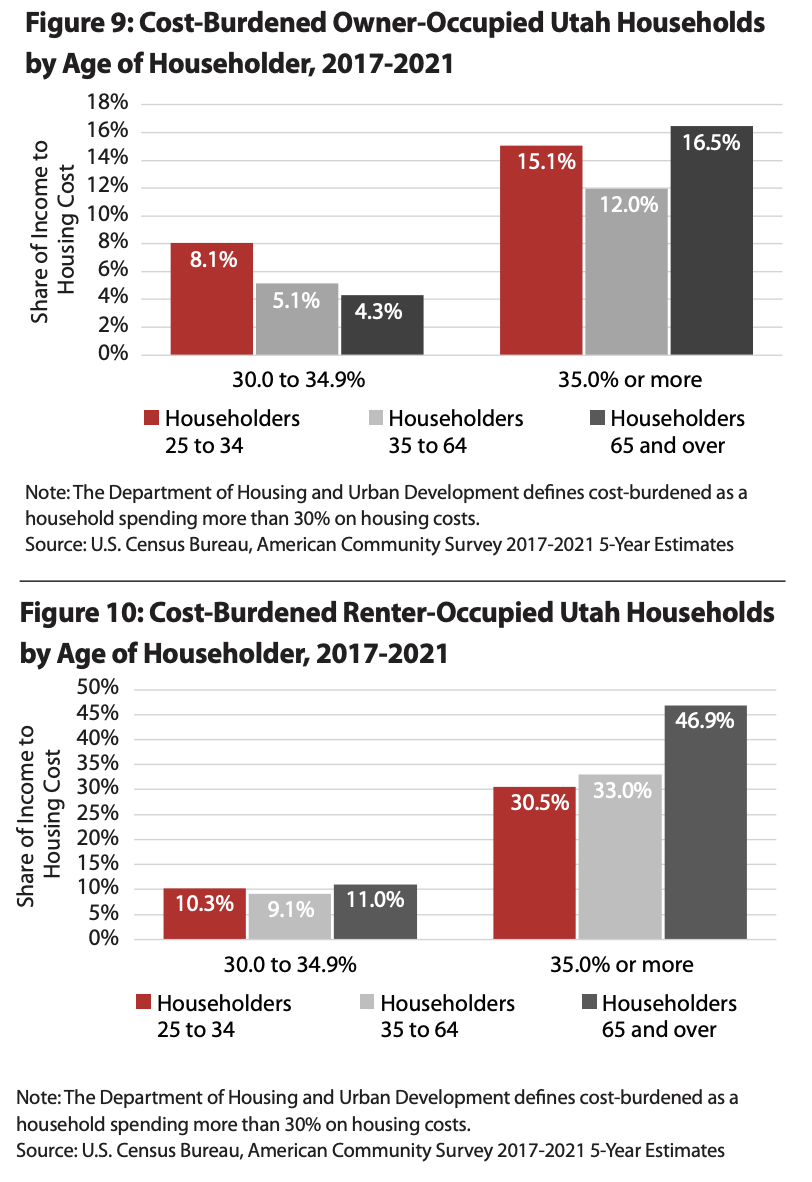

“Nearly 6 of 10 Utah renters age 65 and older are cost burdened, with most householders spending more than 35% of their income on housing costs,” the report states.

That’s compared to cost-burdened rates of nearly 41% of Utah rental households led by someone between the ages of 25 and 34 and 42% of households led by someone between the ages of 35 and 64.

As Utah’s retirement-aged population grows, so will the number of people in the state on fixed incomes, Batemen said.

While many older Utahns own their homes, they might not face the same challenges as renters on fixed incomes — who would be more vulnerable to rent rate increases. However, retirement-aged homeowners could also face other challenges, like rising property taxes or other housing cost fluctuations.

Bateman pointed to a recent New York Times article titled “Aging In Place, or Stuck in Place?” which lays out the challenges aging homeowners can face.

The story notes the proportion of older adults with mortgage debt has been rising for decades. And as housing prices continue to climb amid a nationwide housing shortage, older Americans are struggling to downsize from their large homes into smaller, easier to access and maintain homes. That’s in large part because a “dearth of suitable, affordable homes for older adults makes downsizing challenging even for those with considerable housing wealth,” the article states.

As Utah’s population ages, policymakers will likely want to consider if the state has enough affordable, retirement-friendly homes — whether they’re rented or owned. It’s already a challenging issue given Utah’s housing shortage has been keeping prices stubbornly high.

Bateman added another challenge to consider is whether aging Utahns are able to stay in the community they’ve lived — or if they’ll be forced to move away to afford housing in retirement.

“There’s a lot of different considerations,” she said.

Economy

Utahns, in general, become financially stable throughout their lives until they hit retirement. Then incomes drop and poverty rates increase, the report says.

“Utahns under age 25 earn a median income of just over $43,500, which increases to just over $83,500 in the 25 to 44 age group and then peaks at $99,000 in the 45 to 64 age group,” the report states. “Median income falls to just under $60,000 in the retirement years.”

Meanwhile, “poverty rates peak for Utahns in their young adult years and decline before plateauing in the middle-age years and then rising slightly after age 75,” the report states.

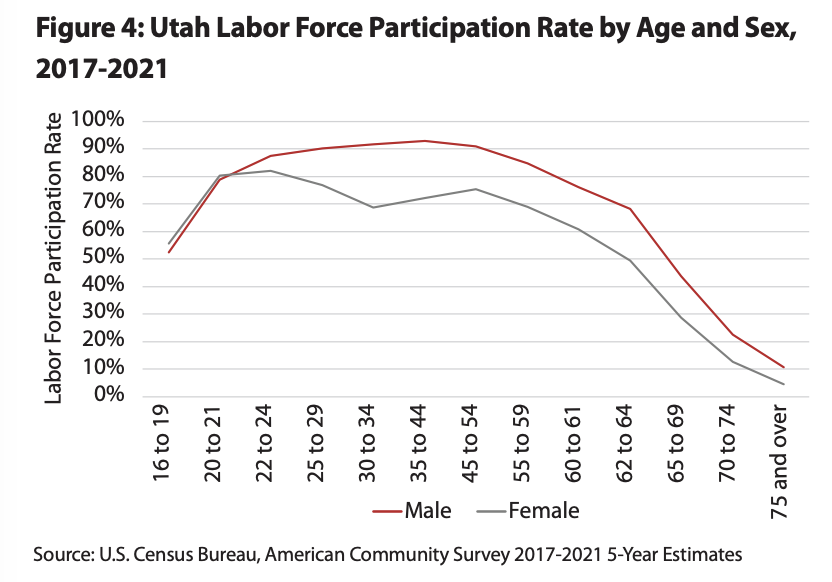

As for the labor force, predictably employment rates drop as Utahns reach retirement age, though work patterns differ between men and women.

“For Utah men, the labor force participation rate peaks in the 35 to 44 age group at 92.8%, though rates exceed 90% from age 25 to 54,” the report states. “Two-thirds of Utah men are still working in the 62 to 64 age group, but in the 65 to 69 age group, labor participation rates drop to 43.7%, signaling a shift to retirement.”

For women, employment rates peak at 82% in the 22 to 24 age group. “In the 25 to 29 age group, rates drop to 76.7% and then fluctuate in the 60% to 80% range until age 55, when rates begin to steadily decline towards retirement,” according to the report.

Currently, Utah enjoys a low unemployment rate, at about 2.8%. But as Utah’s population ages, there may not be enough young people to fill jobs — and the state may need to adapt.

Policymakers need to consider “what does (Utah’s) workforce look like going into the future?” Bateman said, noting nationally the U.S. is seeing “fewer people to fill all the jobs that were created by the baby boom. So how do you deal with those shifts, in staffing, and thinking about jobs and what people need?”

Bateman said Utah is “experiencing this a bit behind the rest of the U.S. … so we can also look to other states and other countries to see how they’ve dealt with these changing demographics.”

She pointed to Vermont, one of the oldest states. As its population ages and fewer young people entering the workforce, it’s become more difficult to replace retiring workers. That can create challenges for the state’s overall growth and economic competitiveness.

Some states, Bateman said, have created programs to “try to entice working-age adults to move to those communities to kind of reinvigorate the community and the economy in a new way,” she said.

Medicare and Social Security

Another issue could have a huge impact on aging Utahns — and aging Americans more broadly.

Officials have warned that federal policy changes are needed to prevent Medicare and Social Security programs from becoming unable to pay full benefits to retiring Americans. Social Security trust funds will be unable to pay full benefits beginning in 2035, only able to pay 83% of benefits, according to the annual Social Security and Medicare trustees report earlier this month.

Medicare’s “go-broke” date, the Associated Press reported, is now estimated to be in 2036. Once the Medicare fund’s reserves are depleted, it’s projected to only be able to cover 89% of costs for patients’ hospital visits, hospice care and nursing home stays or home health care.

Though it’s an issue that requires federal action, Bateman said Utah policymakers should also keep challenges with Social Security and Medicare in mind as they think about Utah’s aging population.

“Any program that interacts with that population 60 and older, 65 and older, is going to have a lot of changes (in the future),” she said. “So having a thoughtful eye when thinking about any of those programs is probably a smart approach.”

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

The post Utah, the youngest state, is getting older. Here’s why that matters appeared first on Utah News Dispatch.