US marshal killed Charlotte man on his birthday. Three years later, his sister is suing.

Both arms bled, the red reaching toward handcuffed wrists.

A group of officers stood above.

It was self-defense, the officer who fired would later say. “We train to hit the target,” he later told local police.

The officers’ tourniquet and bandage would soon fail. So would the paramedics’ attempts. The justice system would never get a chance to try.

Frankie Junior Jennings died outside a Charlotte Citgo around 11 a.m. on March 23, 2021 — his birthday. He was 32 for a day.

His 12-year-old son and fiancee were in a car one gas pump over when Eric Tillman, a senior inspector with the U.S. Marshals Service, pulled in to arrest Jennings and serve him 16 warrants. Three of them stemmed from a confrontation in Carolina Beach: assault with a deadly weapon against a government official, fleeing to elude arrest with a motor vehicle and reckless driving to endanger.

Jennings never made it to court.

“He was never brought to justice… the charges were never proven,” his sister, Tanua Wallace, told The Charlotte Observer in a phone interview.

Wallace now hopes to get her own day in court for a lawsuit she recently filed in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of North Carolina.

The lawsuit challenges the investigation of Jennings’ death conducted by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department and reviewed by Mecklenburg District Attorney Spencer Merriweather. It questions why officers chose to execute a “dangerous maneuver” in a public area and why they used deadly force — three bullets — trying to apprehend her brother.

Tillman and the five other officers serving on the U.S. Marshals’ Carolinas Regional Fugitive Task Force did not wear body cameras. Wallace alleges CMPD relied heavily on officers’ testimony and Citgo’s partially-obstructed surveillance camera.

She also alleges Tillman and the other officers did not properly identify themselves and accuses Tillman of using “excessive, unlawful and deadly force” when he shot her brother in the arms and chest three times. The lawsuit also names the director of the U.S. Marshals Service, Ronald L. Davis.

The lawsuit filed in late March includes new allegations from a family concerned about why a marshal shot Jennings. The marshals service declined to comment on the lawsuit.

U.S. Marshals Charlotte shooting

Tillman and the other marshals had been following Jennings around that day. They started at a hotel — Homewood Suites — and ended up at an auto shop.

“That’s our guy,” Tillman said as he peered through binoculars pointed toward the shop, according to a 2021 police interview attached to a letter the district attorney sent to CMPD’s police chief. The letter cleared the deputy marshal of wrongdoing.

Jennings was standing outside his fiancee’s SUV. Tillman thought about calling for Charlotte-Mecklenburg police backup then, while Jennings was out in the open, “just standing there for a minute,” he said in the police interview.

When Jennings hopped into his Mercedes Benz, Tillman abandoned that plan. One of the warrants he was there to serve accused Jennings of fleeing from officers weeks before, allegedly dragging them with his car.

Tillman said he didn’t want to risk Jennings fleeing and hurting someone in the process.

The gas station would work, he later decided.

“We had enough people to, to safely… make an arrest,” he told CMPD.

As Jennings fueled his fiancee’s car, Tillman decided they’d arrest Jennings there — in between the pump and car. That was a dangerous maneuver known as “vehicle containment,” according to the lawsuit.

They moved in. Tillman, in black t-shirt, green bulletproof vest and jeans, jumped out of his undercover SUV — a blue Chevrolet Tahoe.

Officer Tate Mills — in the same nondescript clothing as Tillman, plus a baseball cap — got out of the unmarked pickup parked behind Jennings’ Mercedes.

Both wore badges.

What happened on the day of Frankie Jennings’ death? Here’s a timeline.

As Tillman and Mills grabbed Jennings, he slipped back into the car enough to put it in gear, Tillman told police investigators.

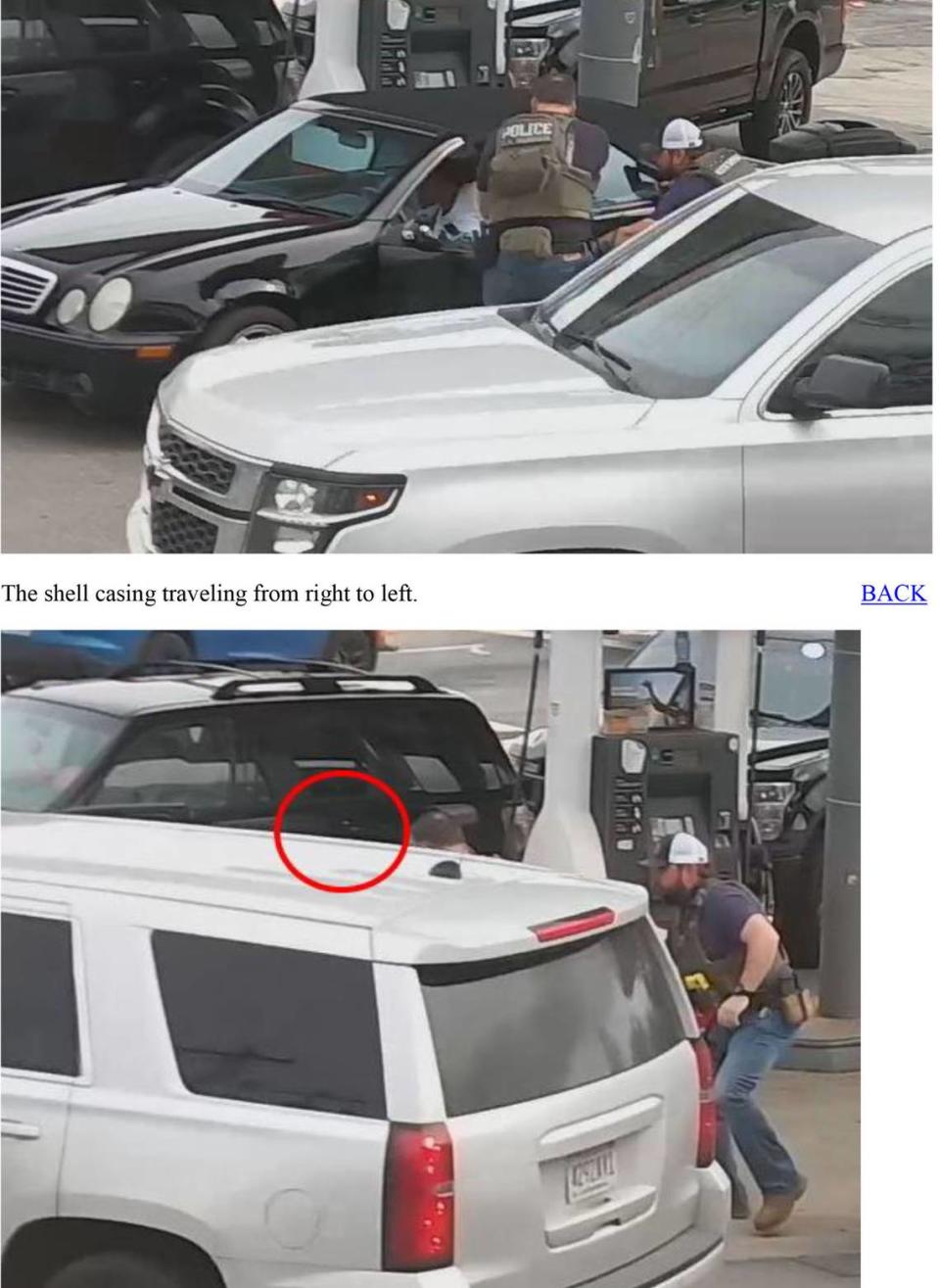

The car moved forward, and Mills started to fall to the ground, Tillman later recalled. Surveillance video does not appear to show any officer falling.

Tillman said Jennings reached toward his cup holder — where a silver Ruger semi-automatic handgun sat.

“That’s when I shot him,” Tillman recalled. “...Like, bang-bang-bang.”

It all happened simultaneously, Tillman said.

“A frame-by-frame analysis of the video appears to show the decedent reaching toward the center of the vehicle with his right hand while his left hand remained up until Deputy Mills began to struggle with the decedent,” reads a letter from Merriweather, the district attorney who opted not to charge the law-enforcement officers.

Moments later, an SUV blocks the camera, making it impossible to see whether Jennings was reaching for a gun when Tillman shot him.

Wallace argues that neither Tillman nor Mills properly announced themselves as police before giving commands to Jennings, further contributing to the “chaos and confusion” of any vehicle containment.

Mills told investigators he thought Jennings knew they were law enforcement “based on his clothing and the lights on his vehicle.”

“When we pulled up, he knew who we were. We had our lights flashing,” Tillman said, “clearly marked as law enforcement.”

Police, during their investigation into the shooting, asked Tillman if he announced anything as he approached the Mercedes.

“I don’t even know,” Tillman responded.

“You don’t know?” the interviewer asked.

“I’m sure we were saying, ‘Give me your hands, put your hands up!’” Tillman said. “Cause that’s pretty typical… I kinda had tunnel vision at that point.”

Video shows Jennings briefly put his hands up before darting into his car.

The CMPD officer interviewing Tillman after the shooting asked him, “I know things are fast … how do y’all train?”

“We train to hit the target,” Tillman replied.

‘Freestyled’ police shooting

Wallace’s lawsuit challenges Tillman’s “freestyled” attempt to arrest Jennings with a risky maneuver in a public area.

Tillman decided not to call for the “multiple CMPD backup units available to aid in the peaceful apprehension of Jennings as he stood for minutes outside of his vehicle while at the car repair shop,” the lawsuit says. He also had no plan for the safety of Jennings, his son and his fiancee, “who were consciously and deliberately” included in the plan.

They could have waited for a better moment, Wallace said.

“I know their job is to stop him… but I don’t see where they were in danger,” she said. “He was outnumbered.”

Statutes governing police use of deadly force are largely open to interpretation. They state that force is justified when it “is or appears to be reasonably necessary.”

Wallace’s lawsuit accuses the U.S. Marshals Service of failing to properly train its task force members to minimize harm.

This shooting, Wallace says, impacted more than just Jennings’ life.

Jennings’ fiancee, with their son still in her backseat, got out of the car and moved to her boyfriend after the shooting. A task force member pointed a gun at her before placing handcuffs on her wrists, video shows.

Wallace has been in therapy since her brother died, she said. She’s had to learn how to explain what happened to her nieces and nephews.

Protesters decry Meck DA decision to not charge deputy US marshal in Jennings killing

Now, she’s reminded of her brother’s last birthday every time the police shoot another person.

“We see it on TV,” she said, “It’s hard to trust them. I probably wouldn’t call them if I needed them. I don’t know.”