US drowning death rates have increased, reversing decades of decline

After decades of decline, accidental drowning rates are rising in the US, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported. With Americans getting ready to hit swimming pools and beaches on Memorial Day weekend, a new study shows that many lack the skills they need to stay safe in the water.

Roughly 15% of US adults – 40 million people – say they don’t know how to swim. More than half of adults have never taken a swimming lesson, according to a new national survey by the CDC. The new data on swimming skills in the US population is included in a Vital Signs report released Tuesday by the CDC.

It comes on the heels of an increase in drowning deaths in the US in the years following the Covid-19 pandemic. Each year, on average, about 4,000 Americans died from accidental drowning, a number that changed little from 2011 to 2020.

But that number has been about 10% higher the past few years, adding 500 to 600 more deaths each year to the annual tally. It’s the first uptick in drowning rates in the US for at least two decades.

“When I just look at the overall numbers, with over 4,000 people dying – that’s over 12 people a day – that’s really one person every two hours. And those are lives, not numbers,” said Dr. Debra Houry, chief medical officer for the CDC.

The increases in drownings were even more dramatic for certain ages and racial groups.

Drowning has long been the leading cause of death for preschool-age children. Drowning rates increased almost 30% in this age group in 2021 and 2022. Although the number of drowning deaths in children ages 4 and younger increased among young children in 2020, the rate increase was not statistically significant that year.

Black people also saw drowning rates increase faster than the general population; compared with 2019, they were nearly 30% higher in 2021. That’s despite the fact that Black Americans reported spending less recreational time in the water than White and Hispanic people. If drowning rates were calculated based on exposure rather than population, the study authors noted, it’s likely that the disparities for Black people would be even more pronounced.

Additionally, the CDC’s swimming skills survey found that 1 in 3 Black adults said they couldn’t swim, compared with 1 in 7 adults in the general population, a legacy of segregation and discrimination in access to swimming pools in the US, according to the CDC.

Hispanic Americans, a group that doesn’t traditionally have disproportionately higher drowning rates compared with White non-Hispanics, also saw drowning rates increase by nearly 25% in 2022, compared with 2019.

American Indian and Alaska Natives continued to have the highest rates of drownings of any racial or ethnic group overall. In 2019, there were about 3 drowning deaths for every 100,000 people among American Indian and Alaska Natives, a rate that has seen little change over the course of the pandemic. By comparison, there were 1.2 accidental drowning deaths for every 100,000 among White people in 2019.

Houry says it’s hard to say exactly how the pandemic may have played a role in the increases. The study can only make associations – it can’t untangle the causes – but she notes that it was harder to get into public pools, with many closing or implementing policies that limited access. Staffing was also problematic for many swim venues.

“There would have been people, if swimming pools were closed for that year, who didn’t get swim lessons and so might have been behind in getting swim lessons,” Houry said.

Berkeley Champlin didn’t know the statistics around drowning deaths in young children until her son, Gordie, tragically became one of them.

In July 2020, 3-year-old Gordie slipped unnoticed out of the sliding glass doors in Champlin’s home in Livonia, Michigan, while Champlin was at work. Normally, he would have been in day care, but like many schools, it was shut down at the time.

His father, who was home with him, later found him in the family’s pool. He couldn’t be revived.

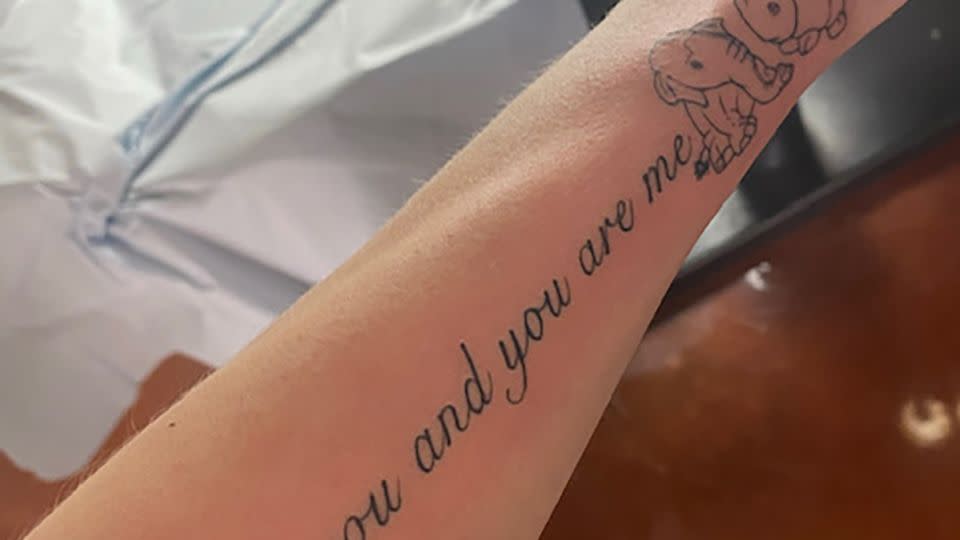

Gordie loved animals and couldn’t go to sleep at night without special stuffed animals: an elephant and a bunny.

“I put his elephant and his bunny in his casket with him so that he has them always, because he’s sleeping,” Champlin said. She has drawings of the stuffies tattooed on her forearm.

“I wish he would have had swim lessons,” she said.

Every year since Gordie died, Champlin has channeled her grief into raising money for swim lessons for other children.

“It’s very expensive. It costs $120 a month in some places for a child to take lessons,” said Champlin, who knows that may put them out of reach for some families.

Champlin set a goal of paying for three kids to learn to swim each year. This year, 42 families reached out to her for help, and she set up a GoFundMe account to raise money to cover them all.

“If anyone else is ever in that situation, or if you go on vacation, or you’re on the lake or a new pool or something that you don’t have your standard parameters around, swim lessons is the way to prevent accidents from happening,” she said.

Houry, from the CDC, agrees.

“I think we forget drowning is still a really big problem for our young kids and that we can do something about it by making sure kids know how to swim,” she said.

Houry said the CDC is funding programs at the Red Cross and YMCA to help lower the cost of lessons and make sure everyone who needs them can get them “because it’s so important to have that equitable access,” she added.

Houry said kids should start getting swim lessons between the ages of 1 and 4.

“If you are an adult and you don’t know how to swim, it’s never too late to get that swim lesson. It’s really important,” she said.

But Houry said that even if kids can swim, adults shouldn’t leave them unattended, drink alcohol or get distracted while watching kids in the pool.

In settings like a party, where it’s easy for conversations or phones to divert attention, the CDC says it can be useful to assign an adult specifically to watch kids in the pool. When swim time is over, the CDC recommends shutting and locking doors that give access to water. In the event that something does happen, learning CPR can help you save a life before paramedics arrive.

Houry says fencing that completely encloses a pool can help make backyard and community pools safer. In open water, like lakes, life jackets are important for safety, too. When visiting a lake or ocean beach, it’s a good idea to take stock of the hazards, such as rip currents, before going into the water.

As Gordie’s birthday approaches on July 12, Champlin said, she finds herself wondering what kind of a party he’d want at age 6. Would he still love animals and superheroes as much, or would it be some kind of gaming thing like Roblox?

Just as in past years, they’ll spend his birthday at the zoo, a place that still holds vivid memories of her son.

“It’s something that doesn’t go away,” she said.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com