Urban development uncovering, disrupting ancient Tennessee Native American graves

WILLIAMSON COUNTY, Tenn. (WKRN) — In January, state archeologists were called to a private property in Franklin after human remains were discovered below the ground.

The discovery wasn’t of a “criminal or forensic matter,” a spokesperson for the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conversation (TDEC) said. Rather, the spot was determined to be where around 1,000 years ago, Native Americans living in the area buried at least nine people.

The burials reportedly took place within or just above a natural cave. They had largely remained undisturbed until archeologists said heavy rains caused an opening to form at the ground surface. Yet, this is not an unusual occurrence in the area.

15+ Native American mounds are a short drive from Nashville

According to Tom Kunesh, president of the Tennessee Ancient Sites Conservancy (TASC), a nonprofit that works to protect and educate people about prehistoric Native American sites, these underground burial sites are discovered on an almost monthly basis in Williamson County.

Most often, Kunesh said they are discovered through construction, with a development boom bringing a number of new housing complexes and commercial spaces to the area within the past decade.

“The question is, ‘What should you do with them when you discover them?’ For most of us, it’s cover them back up, leave them alone,” Kunesh said. “That’s what we would do if we discovered a cemetery, but with the push of development and construction, the constant push to take old land and turn it into new construction sites, new house sites, new apartment sites, there is constant finding and constant destruction.”

What happens when indigenous remains are found

Tennessee state law protects all human remains, regardless of age or cultural affiliation, making it illegal to knowingly tamper with, excavate, or disinter human burials, gravesites, or funerary objects without a Chancery court order.

In the event that a developer encounters or accidentally exposes gravesites, they are required by law to stop all work immediately in the area and notify the medical examiner and local law enforcement.

Kunesh said he believes the “vast majority” of people do report these findings. However, there is a “black market” that exists for trafficking indigenous remains and artifacts. A number of the sites that haven’t been preserved or removed have been destroyed, either by graverobbers or construction.

Centuries after Native American remains were dug up, a new law returns them for reburial in Illinois

“All of these sites are basically known. If they aren’t public, then people are keeping them quiet to preserve them and to avoid pot hunters and graverobbers from coming and looting them,” Kunesh said. “The overt sites, the above ground sites, are well-known. It’s the underground sites that are discovered on a monthly basis.”

After the initial police investigation, some cases wind up in the hands of the state Division of Archaeology, which is typically called in to examine the remains, determine how old they are and make a decision on how to move forward.

“If it’s over 500 years old and its indigenous people, then the question becomes, ‘What do we do with it? Do we leave it in one place? Do we cover it up so that it’s no longer disturbable?'” Kunesh said. “‘Or do we remove it?’ There’s a burial removal law, and that’s what lots of developers do.”

‘I believe that the intent of these people was to be put in the ground and stay’

Under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (“NAGPRA”), which was passed in 1990, federal agencies and institutions that receive federal funding are required to return Native American cultural items and remains to lineal descendants and tribes.

However, reports by ProPublica show that many institutions have failed to fully comply with the law until recently. In a 2023 report, the publication noted that about half of the remains of more than 210,000 Native Americans at institutions across the country had yet to be returned.

Earlier that same year, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) announced that it was taking steps to return the ancestral remains of nearly 5,000 Native Americans that were removed from their original resting places in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Alabama.

Human remains and other objects to be returned from TVA to Indigenous tribes

The vast majority came from Tennessee, with different remains traced back to nearly every single county in the state. According to a database created by ProPublica, the TVA has now made 100% of the remains in its possession available for return, but there are other institutions in Tennessee that still are holding onto hundreds, or in one case, thousands of indigenous remains.

Many of these remains were removed following development projects or excavations of mounds. But even with repatriations, Kunesh, whose family has indigenous roots, said he feels the removal of these ancient remains is likely not what the tribes would have wanted.

“I don’t know what you want to do with your body when you go or if you’re going to get buried or cremated, but I believe that the intent of these people was to be put in the ground and stay,” he said. “I would respect that wish and leave them in place and build around it, or not build at all.”

Preserving thousands of years of history

The site discovered in Franklin earlier this year is an example of what some would consider more positive conservation efforts. According to the TDEC, the site has been recorded in the statewide database of archeological sites and is now considered a cemetery protected under state law.

The Division has since recommended that the city and developer seal the access point in order to protect the burials. The state has also conveyed the protection plan to representatives of federally recognized tribes, who are reportedly supportive of the decision to secure and protect the burial site.

TDEC personnel said they plan to visit the site to ensure these measures have been put in place.

These types of burial sites have been found all across Williamson County and even in Nashville, particularly along rivers and creek sites as Kunesh said the Muskogee people, who were likely in the area between 1400 and 1800, were known to build their villages near water.

Long after tragic mysteries are solved, families of Native American victims are kept in the dark

According to Kunesh, there were tens of thousands of indigenous people who populated the area between Franklin and Nashville around that time period.

However, indigenous history in Middle Tennessee goes back even further, with one of the oldest sites in Williamson County believed to be around 10,000 years old and cultures constructing burial mounds nearly 3,000 years ago.

While some sites have been preserved, the destruction of others has been well-recorded in the past. Along Browns Creek in Nashville, there were over 6,000 indigenous remains found buried in stone box graves that Kunesh said were “destroyed, wiped out, plowed over (and) plowed under.”

Similarly, an old temple mound site in Chattanooga was leveled around 100 years ago to make way for a highway. “It’s gone and now they’ve put up a huge apartment complex, set of complexes there and the best thing we can do is put up a marker and say this is the site of where Citico existed,” Kunesh said.

Existing sites in Williamson County

Of some of the remaining indigenous burial sites is the Glass Mounds Site off State Route 96 in Franklin, which recently gained further protections following the signing of a historic conservation easement agreement in 2023.

While phosphate mining in the mid-20th century, along with looting and excavations, destroyed most of the site, two indigenous mounds dating back to around 1,800 years ago are still standing. The easement was something the TASC and others had been working toward for years and is something that has rarely been done in the past.

“That conservation easement is simply asking for us to be put into the deed as speakers for the site — a conservation voice,” Kunesh explained. “It doesn’t give us any authority, it doesn’t give us any voting power, it just says we have to be contacted when there’s going to be a sale or any change to the land and then we go and we talk and say, ‘Let’s find ways of mitigating destruction or any kind of change to the historic aspects of this site’.”

No children’s remains found in Nebraska dig near former Native American boarding school

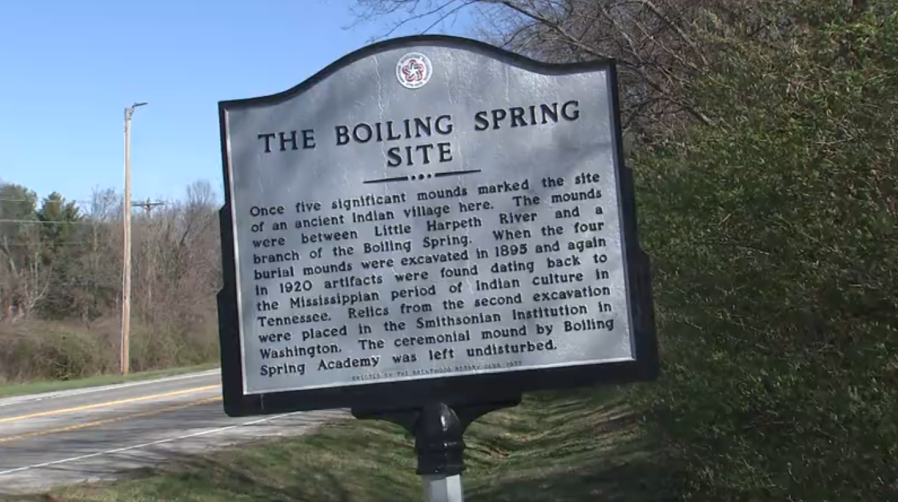

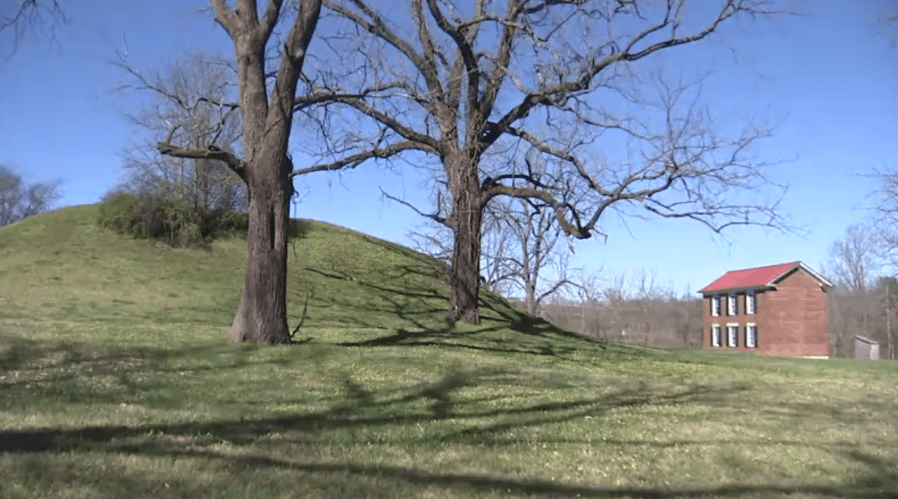

Just a few miles away in Brentwood, the Boiling Spring Site also serves as a reminder of the indigenous people that once populated the county. The area, which now consists mostly of grassy fields and grass-covered mounds, used to look very different.

Sometime between 900 and 1050 A.D., a group of indigenous people are believed to have built a town center there. The town consisted of four mounds, a town square, individual dwelling structures and a separate cemetery area.

A fifth mound located outside of the town center overlooked the Little Harpeth River. The tallest of the mounds at about 25 feet high was likely where the tribal leader’s house was located.

During its prime, Kunesh said the mound would have been shaped like “a pyramid on the sides and flat (on) top. They would put a building on top and maybe some artifacts, carvings, pottery, anything that they considered valuable.”

‘It does our soul good to know relationship of people and places’

To Kunesh, and likely many others with indigenous roots, protecting these sites, whether mounds or underground burials, means not only preserving history but preserving a tribal connection that he never got to learn much about growing up.

“When I live here, I want to know who was here. So, it’s curiosity and the search for knowledge,” he said. “And an identification with place, that even though we move around a lot we still like to say we know something about who is buried under here, who lived here, and I think it does our soul good to know relationship of people and places.”

Kunesh said he hopes that developers will continue to take proactive approaches to protect these burials that are being uncovered by not only reporting them to the state but signing conservation easements or sealing them up.

Hidden Tennessee | Discover some of the Volunteer State’s best-kept secrets

“If people discover, please tell the Division of Archeology, please tell the Native American Indian Association of Tennessee,” he said. “Both places have phone numbers and websites and can be contacted directly and notified and then people will be in contact to say, “What are the choices.'”

The average person can also help out by volunteering with organizations like the Native American Indian Association of Tennessee or Tennessee Ancient Sites Conservancy, which is working to preserve these sites by cleaning off brush and other growth.

To find out more information about how to get involved, visit the TASC’s website here or the NAIA’s website here. The disturbance of human remains or Native American graves should be reported to the TDEC. The correct contact can be found by clicking here.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to WKRN News 2.